At some level I have always known that pornography played a significant role in fueling my desire to leave Vietnam for the West. Of course, there was also the “American dream”: the promise of a better education in a better civilization, a better future for me to then better my backward country. But bubbling underneath this overarching colonial desire to emulate the White Man and be among his equals was also the erotic drive to taste him, to fuck him.

In childhood, the White Man emerged as the de facto object of my queer desire. After diplomatic relations between Vietnam and the U.S. were normalized in 1995, waves of Hollywood movies and music videos entered Vietnamese culture, offering softcore portrayals of his sexual prowess unparalleled by the asexual (or, at best, sexually naïve) depiction of Vietnamese, Chinese, and Korean men on our national television. These images gave the White Man an authoritarian grip over my sexual imagination. Even when the advent of internet hardcore pornography brought other (also fetishistic) options, the White Man’s allure proved difficult to resist. In fact, my imagination found no need for resistance; after all, it was him and only him whom I knew how to lust after.

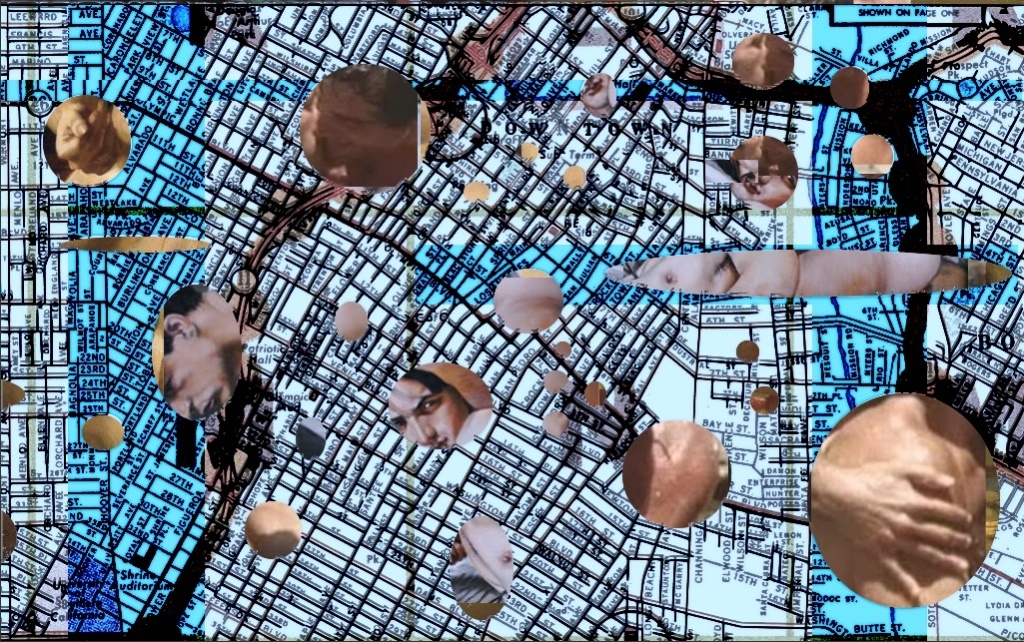

Porn, here, is not a kind of content but a technology that mobilizes bodies in a prescriptive manner

But this is not to say the White Man was a static object of desire. He was a mobilizing force that choreographed the orientation of my sexual body to the extent that I wanted to move across the globe to be physically closer to him, to move inside him — to consume him, certainly, but also to touch the sexual freedom implied by the incessant production and circulation of pornographic materials.

My trans-Pacific migration story is certainly not a peculiar example. In Racial Melancholia, Racial Dissociation, critic David Eng and psychotherapist Shinhee Han draw from Han’s extensive clinical practice to identify in gay male “parachute” children from Asia (i.e., minors whose parents “parachute” them to the West for educational opportunities, as I was) the common desire to seek in the West a (homo)sexual freedom inconceivable in their home countries.

If Eng and Han are interested in the psychic predicaments of Asian migrants produced in the wake of this trans-Pacific movement, I want to stay within the flow of that movement itself and trace the critical role that pornography plays in this choreography of globalization. What is the relationship between pornography and sexual freedom that makes Western countries appear as such desirable locations for us Asian gay “parachute” children?

To begin addressing the problem of pornography and freedom, we need to circumvent the repressive hypothesis that Michel Foucault warns us against. This hypothesis would frame pornography as a freeing of sex from the realm of the private and the taboo — a liberation of pornographic content from its censorship. This view, among its many flaws, fails to account for how freedom can also serve as a form of regulation. It would be more descriptive to think about pornography in choreographic terms: What porn propels is not necessarily freedom of expression but rather freedom of movement, a kind of compulsive freedom that puts bodies in constant motion for the sake of “frictionless” connection, commerce, and convenience.

In this essay, I define pornography not necessarily as a particular kind of content but as a technology that mobilizes bodies in a prescriptive manner, inculcating normative pleasures while commodifying them for capital. Through the circulation of sexually explicit images, pornography can excite and manipulate the movements of our material bodies — our hormones, erections, ejaculations, and muscular mechanisms associated with masturbation and the sex act. In turn, the body’s endless orgasmic potential is constrained within a range of predictable yet profitable formulas: for example, the hand-to-genital motions and vibrations, or the repetitive choreography of kissing, undressing, handjob, blowjob, cunnilingus, penetrating, and ejaculating. These standardized sexual movements directly correlate to profit, so when pornography instills in us the compulsion to move, creating non-stop circulations of physical bodies and digital images, it assures that the flow of capital will remain uninterrupted. Here lies the key to “freedom of movement.” We are free as long as our motion makes money.

This compulsive movement is evident in the rise of amateur online pornography. Its “democratic” mode of production magnifies the volume and intensifies the speed of image circulation, disrupting the monopoly of commercial studios by allowing anyone with a camera and a device connected to the internet to participate in the economy. The slow and costly process of studio porn production is struggling to catch up to the sea of amateur videos proliferating on tube sites (Pornhub, Xvideos) and more recent social media subscription services (OnlyFans, JustForFans) that allow “content creators,” including but not limited to porn performers, to charge a monthly fee for access to their profile page. The price of this “autonomy” is similar to that paid by other vloggers and video-game streamers: The performers, in competition with one another, are under immense pressure to constantly produce and promote their works. In this quintessentially neoliberal economic model you have to always be on the move, otherwise you will be drowned in the image flow.

Looking at hookup apps such as Grindr further reveals pornography’s commitment to circulate the body together with the moving image. What these apps facilitate is the exchange of personal pornographic photos and the bringing together of individual bodies for a kind of instantaneous “right now” pleasure that is ostensibly free but is more often than not formulaic, merely convenient.

In this neoliberal economic model you have to always be on the move, otherwise you will be drowned in the image flow

By facilitating and capitalizing on the convenience and effortlessness of sexual exchange, hookup apps join the ranks of Amazon, Uber, and Postmates as logistical technologies that aim to produce frictionless circulation of goods and services. No more inefficiency, no more unproductive social interaction weighing down the flow of circulation. Grindr users can even choose “right now” as an option, an uncanny resemblance with Amazon Prime Now. This form of “right now” pleasure minimize surprises, imagination, and the erratic possibilities of sexual exchange for the sake of predictability, ease, and convenience. In this fantasy of frictionlessness where anything can be mobilized at your fingertips, you do not get more than the standardized version of sex that is distilled into penetrative act, but at least you always know what you are getting, and can choose when and where you are getting it. Again, freedom of movement is conditioned as programmatic business.

In online commerce, this frictionless reality is propelled largely through the illusion of automation, in which machines invisiblize rather than replace human labor. In her essay “Ill At Ease,” Kelly Pendergrast points out that many technological innovations don’t remove friction but “make the friction occur somewhere else, out of sight of the customer: disappearance as a different kind of magic.” But what happens when the consumers are the ones laboring with their own bodies to find a “right now” sexual experience? Where does the friction of sex — the burden and potential of interpersonal exchange — go?

Hookup apps are quite successful at streamlining sexual encounters, not by replacing or hiding human labor but by making it more machine-like. The shared assumption that everyone is “looking” can allow users to go straight to the point, minimize interaction unrelated to sexual solicitation, and bypass the complex social negotiations that make sexual connection ambiguous and unpredictable. Even in the intimate physical exchange, friction is minimized: In a quick and convenient hookup, there is little “interclass contact” — what writer Samuel R. Delaney describes as a material reckoning with class differences through the meaningful and unpredictable social-sexual exchange, which, according to his book Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, was abundant in the pre-1990s Times Square’s porn theaters.

“Interclass contact” presented the possibility for complex yet rewarding interpersonal negotiations, but our capacity for it has been muted through the technologically abetted process of individualizing pleasure, choreographing the body so that it becomes incapable of producing friction. Each person has their own distinctive pleasure property, their own dating profile, waiting to be circulated and connected to one another without much space for the one to transcend into the many. Sex becomes deprived of its erratic sociality and progressively approaches the model of masturbation, where pleasure is strictly about the fulfillment of one’s own desire.

This individualization process can be traced back to the Enlightenment and the bourgeois conceptualization of pleasure as private property, but more recently, the closing down of public sex venues in the wake of the AIDS crisis, along with the rise of VCR and eventually internet pornography, has further confined pleasure to the private realm. In the midst of such extreme individualization, separation remains intact even when bodies rub against one another, producing not a radical entanglement but something more akin to the mechanical choreography of assembly robots. As automatons, our bodies’ given task is to seamlessly and endlessly circulate. It is not a coincidence that Grindr’s self-description ends with a choreographic command for the users: “Keep connecting.”

To connect for connection’s sake, to move so that more movement can be generated: This is what frictionlessness and freedom of movement entail. In “Mobilization of the Planet from the Spirit of Self-Intensification,” philosopher Peter Sloterdijk locates the compulsion to move at the heart of modernity and its notion of freedom and progress: “To the same degree as we modern subjects understand freedom a priori as freedom of movement, progress is only thinkable for us as the kind of movement that leads to a higher degree of mobility.” Looked at this way, frictionless technologies are very much part of this modern tradition, linking “progress” with efficient circulation. We have no choice but to move freely, Sloterdijk argues: “There is a moral kinetic automatism working that ‘condemns us not only to freedom’ but also to a constant movement toward freedom.”

Each person has their own distinctive pleasure property, their own dating profile, without much space for the one to transcend into the many

Freedom of movement, then, certainly does not refer to unrestrained anarchic movement but to the compulsion to move within only prescribed routes of circulation. Similar to how citizens are “free” to protest provided they do so within a prescribed space, pornographic images are free to proliferate only on designated platforms. When they slip through the cracks of this zoning and show up in art, entertainment, or social media, the images are subject to intense regulation and censorship.

The passage of SESTA-FOSTA, a bill package designed to fight sex trafficking by holding online services responsible for knowingly facilitating it on their platforms, abides the same logic. Sex workers have been banned and shadowbanned on social media sites such as Twitter and Instagram, while other free or low-cost advertising and review sites, most prominently Backpage and Craigslist Personal, have shut down. Those with resources can buy into more expensive platforms and learn how to take advantage of encryption and cryptocurrencies, assuring a more frictionless flow of sexual commerce; those from more marginalized groups (e.g., low-income people, trans people, disabled people, and people of color) may find themselves forced into a different sort of motion — onto the streets, vulnerable to predators and unvetted clients. Thus, “freedom of movement” is not without its regulative logic: Some of us are moving to keep moving forward into a frictionless future, while many of us are moving so as not to be arrested and suffocated by police — moving underground, moving on the streets, moving around to survive, and even moving unto death.

The sexual freedom in the West, which I yearned for while growing up in Vietnam, turns out to be quite an illusion. The incessant circulation of pornographic images does not translate into more meaningful possibilities of pleasure and interpersonal exchange. On the contrary, it standardizes an efficient and convenient form of desire, removes the friction of social negotiation, and produces a compulsive freedom of movement that captures our bodies within the flow of capital.

Nonetheless, what so insidious about freedom of movement and the fantasy of frictionlessness is that it feels exciting to move and to increase our mobility, even if that comes at the expense of your own choreographic imagination as well as others’ ability to mobilize. That is to say, there is real, albeit prescriptive pleasure to be had in going with the flow. Thus, if we are invested in resisting the compulsion to move, we have to first and foremost acknowledge the convenient pleasure we take in smooth and uninterrupted movement before working toward desiring something else.

I believe that pleasure is often a significant missing puzzle piece in the discourse around resistance and systemic violence. Certainly, a lot of weight is rightly placed on the suffocation of oppression and surveillance, which disproportionately targets people from marginalized backgrounds with regards to race, sexuality, ability, and class. But to focus solely on this straightforward “negative” side of violence is to draw a false dichotomy between pain and pleasure, ignoring the fact that what fucks us up the most can also be the engine fueling our desire. Pornography as a frictionless technology makes explicit the possibility of taking pleasure in the very system that subjugates us — pleasure enables our complicity more often than it facilitates our agency.

We have to collectively experiment with more difficult forms of pleasure that do not come with the uninterrupted movement flow. However, it is much easier to linguistically proclaim the need to resist the flow, than to affectively undo our pleasure in convenience, efficiency, and freedom of movement. After all, Western pornography exports the notion of freedom as well as the desire for the White Man that is still etched onto my material body, into my psyche. It feels impossible to refuse the allure of this freedom, even when I can rationalize that one’s freedom always comes at the expense of others, and that one’s freedom is never really free anyway.

Thus, to be critical about pleasure is not enough. It is important to seize the means of pornographic production with our own bodies and to physically explore how our desires can be mobilized differently. One of the most beautiful things about pornographic experimentation is that it is always a public practice — you can explore with your private sexuality all you want but it doesn’t involve pornography until you attempt to sexually move others. It is this orientation toward the collective that will allow us to come together and enact alternative forms of pleasure that can disrupt the choreographic imperative to endlessly connect as individuals.