Our current approach to mobility — gas-powered personal transportation for all — is clearly unsustainable. But the horizon of possibilities to replace it remains chronically short-term and restricted by a bone-deep social commitment to consumer choice. The car, even in the most optimistic futurist proposals, remains an irreplaceable fact of life. Perhaps we can “green” the car, but the car remains, and so does the world it’s created: an ever-expanding universe of individual car ownership and private transportation.

The worst collateral effects of this status quo, meanwhile, show few signs of relenting. An estimated 38,680 people died in motor vehicle traffic crashes in 2020, up more than seven percent from the year prior despite the pandemic and the slight decline in driving miles — which is set to reverse in the coming years, according to data from the Federal Highway Administration. And looming over this is climate change: Transportation accounts for roughly a third of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. — with “light-duty vehicles” such as cars and small trucks making up more than half of that contribution.

As pioneering consumers green themselves, the wider system drags on as before

Before 2020 and its Covid-related slump, global auto production had trended upward for the past 20 years. This is despite the increasing number of battery-powered vehicles like scooters and e-bikes that have found their way onto roads and the demarcated “paths” and “lanes” that parallel them in cities progressive enough to claw back a sliver of real estate from gas-powered traffic. But weren’t the new options supposed to replace cars and not merely diversify the mix of vehicles in an ever increasing pool? Over the past decade, both planners and technologists have pitched concepts such as ridesharing (app-based services that match independent contract drivers with passengers) and micro-mobility (any small, lightweight vehicle that runs at less than 15 miles per hour) as possible alternatives to our dangerous and environmentally destructive transportation system. The assumption is that if given a compelling option, more and more people will choose to change their habits rather than continue driving themselves in their own cars. This is baked into countless think-tank-produced renderings where bucolic pathways spring up alongside highways filled with cars that no longer spew exhaust.

The imagined transformation is often expected to proceed along clear technology-driven trajectories, when in reality the different possibilities will compete with one another and uptake will be unevenly distributed along any number of axes. Presently, on many American streets, possible futures seem to accumulate rather than yield to one another. It’s one thing to imagine a given technology leading us toward a desired or logical endpoint — like a fleet of fine-tuned autonomous vehicles bringing a chaotic, dangerous road network to heel, as imagined in Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report — but another to assume that the path of any one technological solution will happen in a vacuum.

That isn’t to say that a decade of tech-sector-led innovation in mobility hasn’t had an impact on transportation — only that it hasn’t led to the kind of firm break with the past that many imagined. Riding a conventional bicycle down the Broadway bike lane in Manhattan recently, I found myself jostled between a sea of motorized devices, from high-end uni-wheels and e-scooters to souped-up e-bikes ridden by overworked delivery riders, all of which were capable of sustained speeds of over 15 miles per hour. Such speeds are hard to contend with in an already overcrowded bike lane. Traffic in the lane vacillated between too fast and gridlocked, orderly and chaotic, empty and overflowing. Decades of staggered local investment produced one of the best bike-lane networks in the U.S., but now an influx in electric vehicles and delivery riders is helping reproduce the same road conditions that planners had attempted to insulate regular bicyclists from.

If any one of these technologies was actively replacing automobiles — or even putting a dent in the current socioeconomic regime of overwhelming auto dependence — the temporary crowding on bike lanes may be well worth the inconvenience. In this scenario, one could imagine a process in which road users happily consent to the government taking more and more space from automobiles for alternatives that are less damaging to the environment and cheaper to access. Consumer choice and social change thus form a virtuous cycle, as the former drives the latter to the kinds of bold transformations that in time could remake the country’s infrastructure, as cars once did with the highway system.

Judging by the past decade of rollouts, pilots, and partial market penetration, however, it’s possible that these will remain alternatives rather than full replacements — simply more options added to a growing stack, each serving a new niche. Indeed, industry backers of micro-mobility imply as much all the time. Wedged between their far-reaching promises of a slower, greener future are tantalizing hints — at least to their potential investors — of a separate goal: expansion into new markets and new territory.

The most powerful transformation under way on American streets isn’t substitution but accretion, accumulation, addition

Micromobility Industries — an industry group founded on the premise that “transport is moving from monolithic all-in-one owned cars into ever-smaller on-demand vehicles that are optimized for journey length, payload, fleet use, utilization, energy consumed and space allocated” — has pressed the case that “what is today fixed as automobility was once emergent and is as fragile as any modes which came before it — the horse, the canal barge, and the locomotive.” This “impermanence of modes” should give us hope, the group argues, that micro-mobility, like the car, could win the day. Yet, a different post from the same group celebrates the idea that “more people are riding more vehicles further and for more reasons than ever.” This language doesn’t suggest a reckoning with the existing system but rather a coming surfeit of transportation options.

Planners and transportation researchers are largely invested in the premise that new personal transportation modes are capable of substituting for older ones, above all cars. A recent study from C2SMART, a research center funded by the U.S. Department of Transportation, found that a deployment of 2,000 scooters in New York City with 75,000 daily trips could replace 32 percent of carpool trips, 7.2 percent of taxi trips, and 1.8 percent of auto trips. Without scrutinizing the study’s complicated and ultimately speculative methodology, it can be hard to question these kinds of optimistic data points, but they are more rooted in faith than their authors are perhaps willing to admit. Underlying their projections is a firm belief in the possibility of technology-led change.

While other studies also point to a “substitution effect” at the municipal scale, at the macro level, auto dominance continues apace. CitiBike is one of the most successful bike share systems in the country, but in the time since it has operated in New York City, household vehicle registrations have increased by 8.8 percent, increasing the total ratio of car ownership to population in the city to levels higher than the 1990s. In the more car-centric city of Oakland, California, meanwhile, car ownership increased by one of the highest percentages in the country, despite serving as a hotbed for e-scooter rollouts.

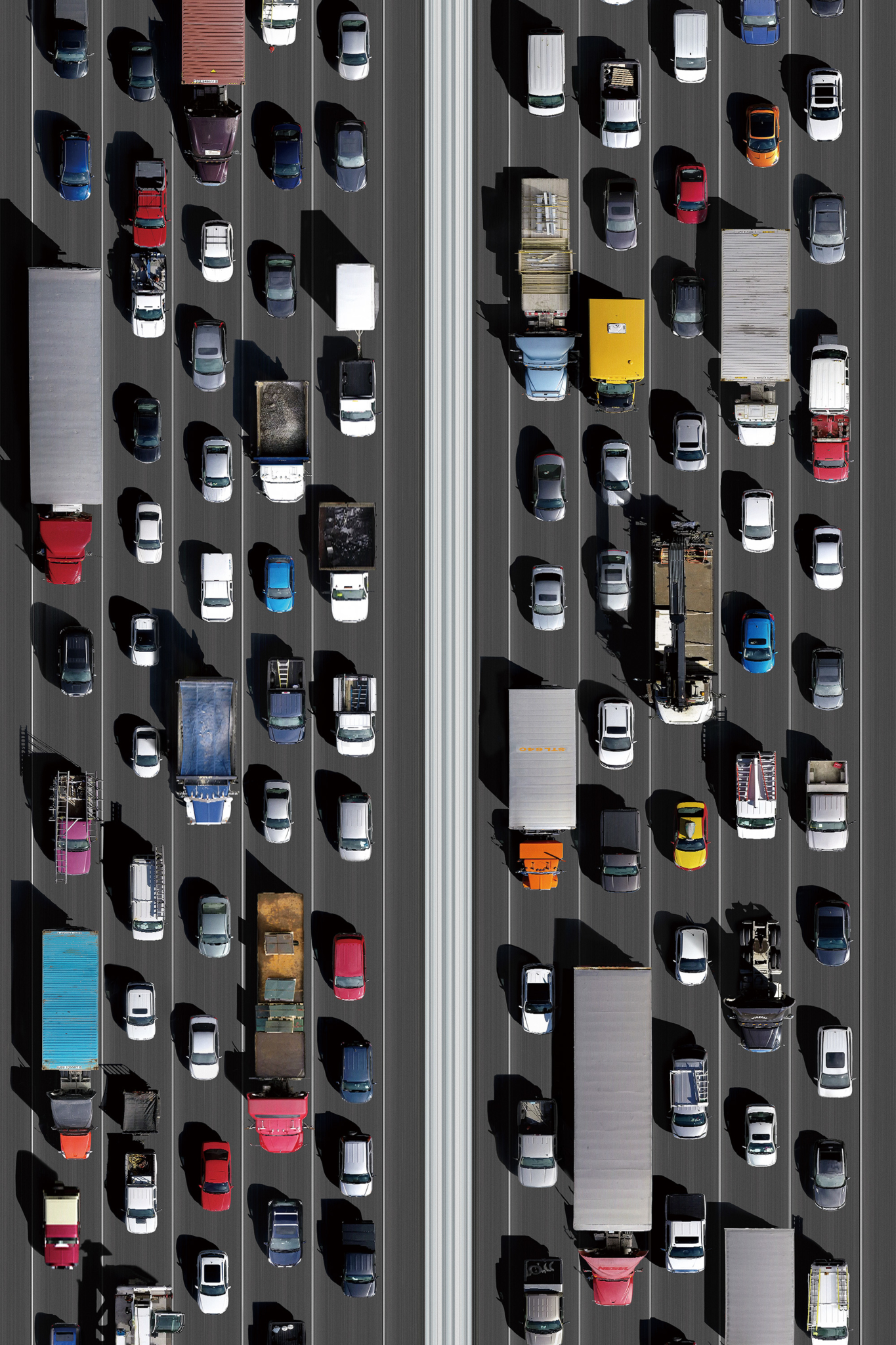

The explosion in ride hailing, meanwhile, has increased vehicle-for-hire use in New York City by 90 percent since 2010, tracking with a national uptick in road congestion that even Uber and Lyft admit is related to their app-based services. The most powerful transformation under way on American streets isn’t substitution but accretion, accumulation, addition. Rather than social transformation, we get endless expansion. In a world where a radical break with the past is desperately needed, this tendency only exacerbates our problems.

Micro-mobility industry boosters notably champion the “non-user,” the untapped market, the unidentified trendsetters who will lead the charge into a new transportation paradigm. The denizens of rapidly growing global cities are of particular interest, as they won’t have the money or space or carbon credits to own a car. They pitch their products not as alternatives to automobiles but as a kind of extender. Where the car cannot reach, either due to new environmental restrictions or just the sheer limits of space in dense megacities, the scooter, the e-bike, and the uni-wheel are there to make sure speed, convenience, and the fluidity of commerce are not sacrificed.

Nowhere is this more apparent than on busy urban bike lanes. Designed as a parallel road network for bicyclists to ride apart from high-speed car traffic, they are now becoming commercial highways for delivery riders compelled by hidden algorithms and the competition between their absentee employers to accelerate, accelerate, accelerate. The war between delivery platforms is waged in fractal increments, flooding out of overcapacity into under-capacity, from thoroughfares to backstreets, as markets become space, and space the market. Competition seizes upon the new transit possibilities only to push them to the maximum, so that no congestion is relieved, and any substitution effect is overwhelmed by the creation of new markets. All we get are busier and busier roads, with piecemeal additions that only induce more demand. Adding more lanes to highways has never eased traffic congestion but intensified it, while distracting from the underlying causes that produce it. Micro-mobility options threaten to have a similar effect, an apparent solution that in practice sustains the ways of life that have yielded the flawed transportation system they’re trying to fix.

Between far-reaching promises of a greener future are tantalizing hints of a separate goal: expansion into new markets and territory — more options added to a growing stack

This is apparent when battery-powered vehicles are treated not as a necessary shift in approach but as a style trend, a way for early adopters to stand out. On the other end of the battery-powered-vehicle market from delivery riders, wealthier people are buying into a consumer fad more than they are spurring a transportation revolution. “This Unagi scooter freakin’ jams. It makes just buzzing around so much fun,” former presidential candidate Andrew Yang said in a promotional video for an up-and-coming scooter company. Similar to the Tesla car in its early incarnation, owning a scooter is presented as less about saving the world than affiliating with cutting-edge technology and culture for its own sake — a way to bring a little piece of Silicon Valley’s utopian dreams into your garage. As pioneering consumers green themselves, the wider system drags on as before.

None of this should discourage us from attempting to adopt new transportation technologies. But a theory of change that gives too much credit to consumer choice misses the need for a bolder set of transformations requiring social coordination that sometimes precedes the mass adoption of a new technology. In other words, sometimes you have to build it for them to come, and that requires a social vision beyond simply waiting for the latest tech to draw consumers away from the comforts of the status quo.

Unless scooters are joined with a more ambitious, holistic social reorientation away from automobiles, they are more likely to end up as just another vehicle on an ever-growing scrap heap. Scooters, e-bikes, and even old-fashioned pedal-powered bikes must come with more designated trails and lanes that reclaim space from automobiles. They need to effectively and on a large scale take back space from the automobile. Yes, this is a zero-sum argument, but in transportation — bound as it is by the physical world — that’s exactly how it needs to be framed to properly prioritize desperately needed changes. Something, somewhere, has to give, and the world has to turn down a different path.

Like autonomous vehicles, scooters and e-bikes are persuasive as harbingers of a new transportation future precisely because they embody the famous maxim from Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s novel The Leopard: “Everything must change for everything to remain the same.” Right now, staying the same means more transportation choices with the same promises of convenience, speed, and autonomy — but a little greener, for the kids — within the same weathering infrastructural territories. Bike lanes and roads built decades ago will be forced to bear most of the weight of all possible futures and every techno-choice on the market, regardless of their capacity or state of maintenance. The micro-mobility industry may want endless options, but there is just one road network, and the competitions being waged on its surface are heating up despite its physical limits.

If planners and well-meaning technologists — or the wider public that follows their lead in conceptualizing the future of transportation — can’t recognize the real commercial imperatives and emergent consumer demands (cheap autonomous travel in a world of higher costs and greater restrictions) fueling the adoption of new modes of transportation like e-scooters and e-bikes, they might find themselves indulging in a bland consumerist utopianism, in which venerating choice actually denies choice. On the streets, in the throngs of competing mobilities, more and faster become the only option.