Last spring, California poppies bloomed on my screen before I saw them bloom anywhere else. Among the flowers, on Instagram, there was often a person, most often a white woman, posing in the orange-studded hills, selling something. I imagined others like me viewing these images from spaces devoid of whatever sense of carefree, adventurous leisure the flower-strewn landscape was meant to evoke; in cramped subways, or bedrooms, or cubicles. But there was something more than outdoorsy aspiration that made the poppies such a hackneyed backdrop for these kinds of posts. The bloom — a “superbloom,” occurring after an uncommonly undisrupted desert incubation period — was somewhat rare and remote. The news had to break, then one had to travel there, had to climb. Behind each model’s radiant effortlessness lay the more covetous appeal of their effort conveyed by the landscape.

Photography was crucial in fostering a consciousness of conservation, and determining how these places were framed and consumed

Then came the vigilante accounts, with names like OUR PUBLIC LANDS HATE YOU and NATIONAL PARKS HATE YOU. Joshua Tree? Hates you. Big Sur hates you too. Although no one was spared from this implicative second-person address, the accounts’ scorn was especially directed towards influencers who trade in environmentally insensitive spon con, or those “prioritizing profit, fame, and ‘rad pics’ over the health and future of our favorite places.” Soon the self-appointed public land defenders turned the attention economy against its most devoted exploiters by using the tools of their trade: Instagram posts of poppy frolickers were tagged and written up for their offenses. These included but were not limited to straying from trails, trampling the bloom, picking the flowers, climbing on Joshua Trees and risking the delicate limbs, stacking rocks, driving their cars across flower fields, letting their dogs roam without a leash, and feeding deer. Unsurprisingly, the shame-posting proved highly effective. Photos were deleted and sponsorship deals were lost.

“Public lands,” the man behind @publiclandshateyou said in an interview with writer Anna Merlan, “are not props for influencers to try to sell what they’re selling.” He was particularly distressed by what photographer Tom Seelie coined “The World Is For Me.” “TWIFM means that everything is your prop, your photoshoot backdrop,” Merlan tweeted. “Everything exists to serve you. Everybody else’s needs are secondary. Influencers have chronic TWIFM.” It’s noteworthy that a photographer diagnosed this “gross behavior” — it could be more accurately called The World is For Me to Photograph. Influencer or not, social media users are incentivized to find in each moment the possibility for content. For many who trade in the attention economy, whose livelihood is in some way connected to the demands of maintaining a social media “presence,” The World Is For Me is not a diagnosis of some narcissistic syndrome, but a description of a labored affect, a job task.

But most distressing, perhaps, is the concept of public land itself. There are 640 million acres — nearly half of the 11 coterminous western states — of federal public land in the United States, enormous swaths of mutually-owned, unappropriated earth, managed by the government. The several federal agencies that manage public lands have different, and at times conflicting, mandates: some, like the Bureau of Land Management, implement a “multiple-use” policy that allows unrestricted recreation and resource extraction — BLM just as often welcomes camping and hiking as it does drilling and grazing — while others, like the National Park Service, are focused on conservation. Conservation requires a more delicate balance between restricting use in order to conserve the “naturalness” of national parks while facilitating use to build the public’s investment and bolster the case for their protection.

In photographing it or yourself in it, public space, otherwise held under a collective pact of mutual use and access, becomes an experiential commodity. Of course, the compulsion to use the natural world as background, prop, subject, or stage for photographing long precedes the demands of the attention economy. It also precedes, and is in part responsible for, the desire to conserve and protect public lands, themselves places where communal use and value extraction are, at times, indistinguishable impulses.

Carleton Watkins had not intended to become a photographer when, like many in the mid 19th century, he came to California looking for gold. Instead he unwittingly ended up working as a studio photographer in San Francisco before an expedition to Yosemite Valley in 1861. Only one other photographer retains early historical credit — Charles Leander Weed, who had been sent by Englishman J. M. Hutchings in the year or so before Watkins, for a feature on traveling to Yosemite in an inaugural issue of his Illustrated California Magazine. But Watkins’ photographs would be remembered as the progenitors to landscape photography as an artistic practice. His mammoth-plate camera, its size befitting the scale of its subject, took in every fissure of rock, every sprightly tree limb, every quaking leaf in its frame. His photos were so sharp, present-day botanists have looked at them to identify foliage. At the time, photography was a nascent technology; Watkins reportedly lugged 2,000 pounds of equipment on the backs of 12 mules.

Yet, the images trace none of this effort. They don’t even seem to trace time. The rock faces of Yosemite stand as timeless monuments, mute and still. They were also empty, at least of people. The limits of photographic technology at the time were in part responsible — the long exposure demanded a stillness difficult for people to accommodate outside of a studio. But it’s also as if that human void complemented the immortal stature of Watkins’ images.

“Two types of landscape photographs,” curator Elizabeth Kathleen Mitchell wrote, “circulating in Washington, D.C., after 1861 influenced national policy: the horrific pictures of Civil War battlefields, and Watkins’s views of Yosemite, the vast Pacific paradise.” Three years after Watkin’s first excursion to Yosemite, amid the devastation of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant Act into law, establishing Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove as protected wildernesses. Paradoxically, the allure of a vacant and isolated nature attracted crowds of tourists; Watkins’ photographs, as another curator puts it, “clinched the deal.” The bill marked the first time the U.S. government had designated a piece of land for public use and preservation, paving the way for the National Park Service Organic Act, signed by President Woodrow Wilson in 1916, that established the National Park system still operating today.

The seeming absence of human intervention in these photographs became a value in itself

By the 1870s selling photographs of Yosemite was good business. People who couldn’t access the remote wilderness still wanted to take in its grandeur, and people who did wanted to seal the experience with photographic evidence. Photographs of “untouched” Yosemite often underwent human alteration: Eadweard Muybridge, made famous by his 1867 photographs of Yosemite, inserted feathery clouds into his wet-collodion prints. Well into the 20th century, each new national park created its own industry of photographers who set up nearby studios, sold their prints of the landscape, took people’s portraits, and eventually processed visitors’ film.

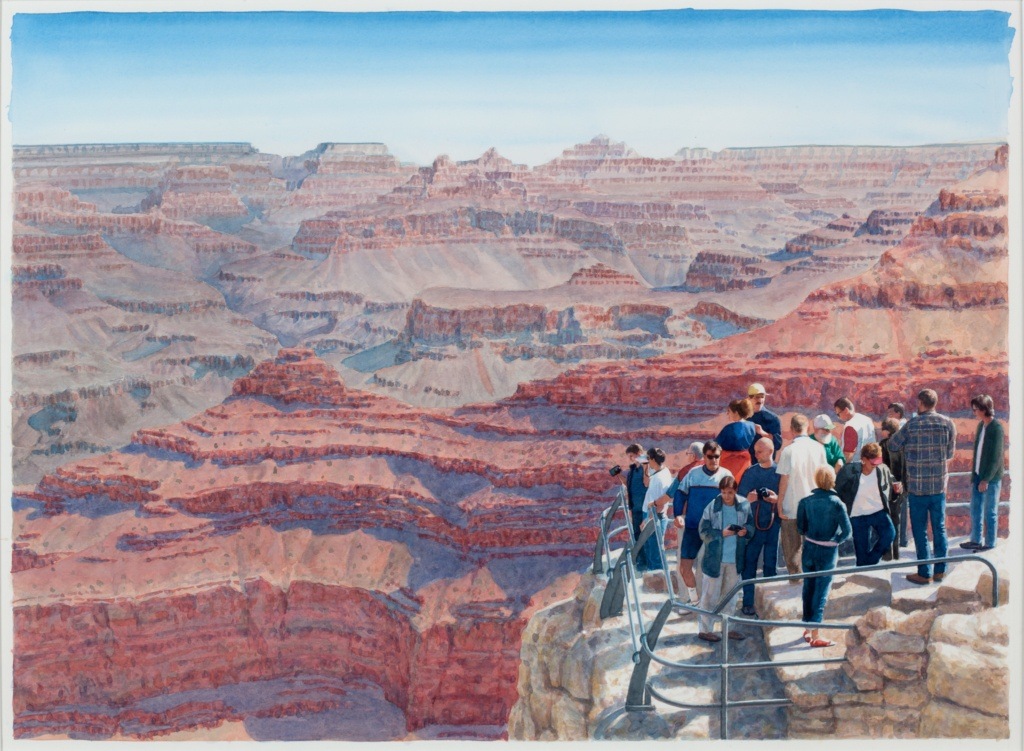

Photography was not only crucial in fostering a consciousness of conservation of public lands, but it also determined how these exceptional places were framed and consumed. This happened literally; Watkins’ shots became the canonical images that photographers and tourists reproduce again and again, to this day. They are what we see in our minds when we think of “Yosemite” or “the Grand Canyon” or “Yellowstone” — the solemn mountain face jutting from lush pine forests, the red and pink undulations of an unending canyon, the spurting geysers — and what we look for when we visit. The seeming absence of human intervention in these photographs, and by extension the places they captured, became a value in itself, to be protected, especially when cast against the rapacious mining and logging that was overturning vast swaths of the west. The “landscape” in landscape photography, still and empty, retains a certain Edenic fixedness, as if divined. It is scenery, untouched, poised for us to photograph or to protect. These images suggest, Rebecca Solnit writes in Savage Dreams: A Journey Into the Hidden Wars of the American West, “a place where nothing has ever happened and no human has ever touched: They are the birthplace of the photographs of virgin wilderness that feed the continuing appetite for exploration and for conservation.”

Car culture has meant more people could access protected public lands, but it also meant in order to increase access, the National Park Service had to build roads through the parks, create campsites, visitor centers, and bathroom facilities, further casting the meaninglessness of maintaining the “natural state” of these parks. In 1995, evolutionary biologist Elizabeth Losos studied all the factors that led to species loss in public lands and found that recreation — skiing, mountain biking, off-road vehicle use, even hiking — was the second leading cause, after water development. Corporations like REI, The North Face, Patagonia have turned “outdoor recreation” into a $400 billion dollar industry (these corporations are some of the most vocal advocates for public land conservation since their business models rely on it). Meanwhile, national park attendance has grown from around 275 million visitors in 2013 to over 330 million in 2017. The symptomatic “rad pics” of TWIFM are extensions of the successful public outreach to increase recreation in National Parks that in turn provides key revenue for land conservation projects. Like the images that drove it, the system of national parks meant to conserve nature’s “naturalness” has also, paradoxically, spurred its development.

The last plot of land in the contiguous United States to be mapped — in 1872, by a Civil War veteran in a surveying expedition funded by congress on the cusp of the Black Hawk War — is now part of the Grand Staircase-Escalante Monument in Utah, an isolated, staggering landscape managed by BLM. The Grand Staircase is precisely that, a stepped slope of eroded earth in southern Utah, each successive cliff exposing a new shade of rock: pink, gray, white, vermillion, chocolate, descending ridge-by-ridge towards the Grand Canyon. Last summer, I stopped mid trip and camped on the southern tip of the Monument. The fact that I had access to this — an isolated, staggering landscape, where I could stay for free — astonished me.

Days after I pitched my tent there — anywhere you want, a ranger had assured me — I learned BLM, which manages three times as much land as National Park Service, released a plan to open 700,000 acres of the Monument to potential mining and drilling following an executive action to reduce and splinter it, signed by President Trump. In 2017 the Trump Administration similarly opened 85 percent of the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah to extractive practices and cattle grazing. It is responsible for the largest reduction of public lands in U.S. history.

It never occurred to the first white settlers who came to Yosemite and exclaimed that it had the pristine beauty of a European garden that it was a garden

These plots near the Monument, where 19 corporations have now requested to open operations, are publicly represented by a BLM office in Kanab, Utah. I stopped by the office and walked through an exhibit on the Monument. On one wall, a floor-to-ceiling gradient of pastels represent the geological strata visible from the staircase’s steps, like a creamy layered cake of deep time. Another listed the fossils excavated in the site: fish, turtles, sharks. The arid desert had once been an ocean. Another had several photographs of canyon walls within the Monument, where Ancestral Puebloans had engraved images of a flute players, of woven tapestries, of bighorn sheep. One canyon wall had been etched with hundreds of small hands.

Before Yosemite became a joint tourist attraction and conservation cause, it was a war zone, and before that, an indigenous home and stronghold. In 1851, just 10 years before Watkins came with his camera, the Mariposa Battalion became the first group of white settlers to enter the Valley intent on removing, by force, the Ahwahnechee living on mineral-rich land. Most of what is known of the conflict comes from an enlistee’s memoir. In one scene, Tenaya, leader of the Ahwahnechee, meets with the captain of Battalion. His community is about to be escorted out of their land and onto a reservation in the dry flatlands of the San Joaquin Valley. They stand at a lake; the captain informs Tenaya that it will be named after him. “It already has a name, we call it Py-we-ack” (which roughly means “shining like rocks”). The captain responds that it will now be known as Tenaya Lake, because it was “upon the shores of the lake that [the Battalion] had found his people, who would never return to it to live.” Twenty-five years later, John Muir, future co-founder of the Sierra Club and an early advocate of conservation, found himself camping on the lake’s shores. He knew nothing of Tenaya, of the theft that had happened there, that the name of that place was salt over an unforgivable wound. “This is my old haunt where I begin my studies,” he writes of the place. “I camped on this very spot. No foot seems to have neared it.”

Yosemite’s emptiness was never evidence of Eden, but proof of recent extermination and removal (Muir was either alarmingly naive or willfully ignorant of this fact). Still, environmentalists continue to mourn “nature’s independence” as Bill McKibben imagines in The End of Nature. If to McKibben or Muir, as Solnit writes, “nature in a natural state is nature without people,” to the National Park Service, nature is something to be managed in order to keep it natural. This myth has spurned devastatingly foolish policies, like the active suppression of fires in the Sierran forests: What stronger symbol than fire to rattle the vision of an undisturbed wilderness? The forests, in fact, need fire, to clear lower brush, to aid certain trees in reproduction. It is now widely accepted amongst forest managers that indigenous people regularly set fires as part of broader practices to actively cultivate and tend to the forest. It never occurred to the first white settlers who came to Yosemite and exclaimed that it had the pristine beauty of a European garden that it in fact was a garden, that this untouched wilderness was formed from intentional and continual human interaction.

Both photography and conservation, as much as recreation and extraction, are entangled with conquest. In this light, “defending public land” looks more like defending appropriated loot. Still, many of the most actively involved in fighting development of these places, as is this case with Bears Ears and Grand Staircase, are indigenous people who, despite relentless attacks, never left, and whose ties to these places are determined by more than some abstracted notion of “public land.” While, like a sensible guest who leaves a place as they found it, there is some practical adherence to certain environmental ethics like Leave No Trace, the attachment to a sense of unspoiled wilderness perpetuates the very myth that most threatens them: that these lands were unpopulated, that before they became camping spots, no foot neared them. Prior to conquest, California was the most populated place on so-called America; what we now call wilderness was formed by their trace.