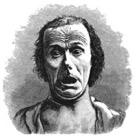

Look at this face. What is this person feeling? What experience could have produced this abyssal countenance: eyes wide, brow scrunched, chin withdrawn and mouth gaping, as if he were screaming from that low, guttural place at the back of the throat?

Charles Darwin used this image — adapted from a photograph by French proto-neurologist Duchenne de Boulogne — in his 1872 work The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, to help illustrate his theory about the evolutionary origins of human emotional expression. The book reoriented the scientific discussion around the face’s meaning away from physiognomy (study of the underlying skeletal structure) and toward pathognomy (study of the face’s mobile expressivity), laying the groundwork for the evolutionary-biological paradigm that has dominated scientists’ interpretation of the human face ever since.

It tends to be taken for granted now that we can “read” faces. We see in them the characteristic patterns of muscle contraction that we intuitively associate with a specific emotion: A smile means happiness; a frown indicates sadness; a scowl, anger. This simple logic pervades how we talk about faces — what we think they can mean and how they’re represented in media. It also underpins — in rationalized and quantified form — the various “emotion detection” systems currently being developed and marketed by startups such as Emotient, Realeyes, and Affectiva, as well as corporate behemoths Microsoft, Amazon, and IBM. These systems purport to discern an individual’s emotional state by analyzing real-time footage of their face. Broadly speaking, they often work by mapping the relative positions of a range of facial “landmarks” (the corners of the mouth and eyes, the tip of the nose), then matching these to a set of emotional templates. The results are generally expressed as a probabilistic percentage score, which allows for the simultaneous presence of different or even contradictory emotions in a single facial configuration. At any given moment, for instance, your face might be read as 56 percent contemptuous, 31 percent afraid, and 13 percent joyful.

A set of assumptions have fed directly into emotion detection technologies, one being the tendency to treat facial expressions as a stable code for emotions

If this emotional calculus seems transparently absurd, we ought to remind ourselves that the developers, investors, and clients engaged in making and deploying these technologies are deadly serious. They are already being applied in fields as diverse as marketing, workplace management, security, and surveillance, offering new ways for authoritarian capital to control and extract value from the human body. And while the scenarios they enable — travelers detained at airport security because their faces display signs of “malintent,” job applicants being rejected after revealing anxiety or exasperation to an automated interviewer, service workers sanctioned for demonstrating insufficient joy — might seem like the bleeding edge of capitalist dystopia, it is also true that “automated facial analytics” is ultimately grounded in the same common sense that suggests a smiling face denotes a happy individual.

If we return to Darwin’s Expression of Emotions, however, we find that these ideas are neither as timeless nor self-evident as they might at first seem. In fact, at the time of their emergence, Darwin’s arguments about emotional expression were just as heterodox as his more famous work on evolutionary theory.

Until the beginning of the 19th century, almost all systematic attempts to codify the face’s meaning focused on the underlying skeletal structure, which was thought to indicate an individual’s general character: A high forehead suggests intelligence; a prominent nose, strength of will, and so on. This is what is meant by physiognomy, an interpretive discipline with roots that reach as far back as ancient Greece and that persisted well after Darwin, in the field of eugenics as well as in a range of institutionalized racial ideologies. It also lives on today in some data science initiatives that seek to detect not just emotion from faces but an individual’s personality traits or behavioral tendencies from their facial morphology.

To a physiognomist — such as the Swiss theologian Johann Kaspar Lavater, writing in the late 18th century — the face’s fixed contours provided the basic framework through which individual subjectivity was mediated. Measurements such as the size of the nose or the angle of the brow relative to the jaw were understood to be the external expression of the metaphysical essence that defined the limits of a person’s character. Facial expressions were only meaningful within this underlying, determining context. A person with the firm, vertical bone structure that Lavater associated with spiritual nobility, for instance, would be able to smile beatifically or magnanimously but never lasciviously, because lasciviousness was simply beyond the scope of possibilities implied by their bone structure.

Lavater’s aim here was to invent, at a time of extreme political and social volatility, a putatively biological (and therefore immutable) basis for the emergent class-based social order, a means of organizing individuals into a hierarchy that could be read visually even as the old feudal signs of rank were losing what remained of their currency. The fixed forms of the face signified the permanent distribution of vices and virtues throughout the various “orders of man,” circumscribing the limits beyond which a “rational” reorganization of the social order could not proceed.

Physiognomy, with its belief in immutable human essences, not to mention its lack of any basis in the developing anatomical, biological, and neurological disciplines from which Darwin drew his evidence, stood in obvious contradiction to his broader theory of evolution by natural selection. One of Darwin’s proximate goals in writing Expression, therefore, was to reverse the terms of physiognomy, asserting that the deep structure of subjectivity is not to be found in the face’s hard foundations but rather its mobile musculature.

He was by no means the first to attempt this. His work was preceded by figures like Duchenne and the Scottish polymath Sir Charles Bell, Darwin’s most important Anglophone influence. However, these earlier pathognomists also cleaved to positions incompatible with Darwinian theory, claiming that facial expression was a uniquely human faculty, granted by humankind’s benevolent creator for the purpose of communicating matters of the soul.

Darwin’s desire to refute this creationist account of facial expressivity drove him to adopt a seemingly counterintuitive rhetorical strategy. Determined to counter the argument from design, Darwin kicked in the opposite direction, claiming that facial expressions were better understood as atavistic vestiges of previously “serviceable” behaviors from further back in the evolutionary lineage. They were essentially physical reflexes, rooted in the way our ancestors coped with the challenges of their primordial environment. The open-mouthed, wide-eyed expression generally associated with fear, for example, was simply part of the body’s broader physiological response to a perceived threat, which would also include phenomena such as the stiffening of hairs, a pounding heart rate and rapid breathing — essentially, all the requisite preparations for fight or flight.

Altogether, these behaviors form what later researchers have described as an “affect program,” the list of physiological responses which define an emotion according to post-Darwinian evolutionary psychology. Affect programs and facial expressions, it is argued, do not evolve because their communicative functions have adaptive benefits. They are a relic of the prehistoric human animal, passed down to today through force of association even after the violent world which shaped them has disappeared. This line of reasoning has profound implications for the way we see both emotions and facial expressions — a set of assumptions which have fed directly into the design of contemporary emotion detection technologies.

Facial expression is only one element of an affect program, but it is the most visible and easily recognizable. From this stems the tendency to treat facial expressions as a stable code for emotions in general. To his credit, Darwin in the Expression is generally tentative and circumspect about this semiology, and his emotional categories are both internally varied and blurry at the borders. His successors, however, have inherited little of his caution. From the 1960s onward, the self-proclaimed heirs to the Darwinian tradition have sought to establish a repertoire of “universal” or “basic emotions” indexed to stereotyped facial expressions. The most influential empirical research in this field typically amounts to showing people a photograph of a face alongside a list of preselected “emotion words” and asking them to pick the most appropriate match, the results of which are most commonly presented as a list of six canonical expressions: happiness, sadness, disgust, fear, anger and surprise. This list has in turn provided the fundamental categories on which contemporary emotion detection technology is based.

Given the correct training, the logic goes, an objective observer can tell a sincere smile from a fake one. The subject’s own feelings are beside the point

Darwin’s work helped produce a sea change in how the relationship between the human face and subjectivity was understood. Personhood was no longer to be described in terms of a list of moralized characteristics (intelligence, stupidity, virtue, wickedness), but as a movement through a series of affective states. Who we are is defined by what we feel, not by an inherited and immutable metaphysical essence.

To this extent, Darwin’s account of emotion constituted not only a rejection of physiognomic essentialism but also a limited refutation of the attempts by late 19th-century eugenicists and racial scientists to rearticulate physiognomy’s hierarchical world-picture. (See, for instance, the criminology of Cesare Lombroso, or the eugenic theories of Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton.) However, in the long run, Darwin’s ideas have served to release humanity from one form of determinism only to encase it in another. It exchanges the determining framework of facial morphology for a set repertoire of purportedly hard-coded affect programs rooted in our evolutionary inheritance.

Since, in the Darwinian view, emotions and their associated facial expressions are seen as reflexes, the subject is in no way the author or proprietor of what would erroneously be called “their own emotions.” Instead, an absolute empirical criterion for “authentic emotion” is established, consisting of stereotyped physiological responses triggered by the appropriate stimuli. Any attempts to consciously communicate emotional states to others are implicitly (and, as evolutionary psychologist Alan Fridlund puts it, “crypto-moralistically”) understood as a kind of feigned performance.

This distinction in turn lays the groundwork for distinguishing between “true” and “false” displays of emotion purely based on whether they exhibit the correct physiological markers. Given the correct training, the logic goes, an objective observer can tell a “sincere” smile from a “fake” one by which muscles are activated. The subject’s own feelings about the sincerity of their feelings, meanwhile, are strictly beside the point. The ultimate authority to decide what a person is feeling is located outside that person’s experience and beyond their capacity to describe it. Whether they like it or not, the truth is written all over their face.

The new generation of emotion-detection technologies systemizes this principle. Sufficiently extended, it would effectively dispossess people, as individuals and groups, of the ability to narrate their own emotional experience. The perverse consequences of this affective coup are already perceptible. For instance, it’s been reported that some jobseekers in South Korea have started undergoing special training to learn to perform the “correct” emotions for the AI bots companies are using to screen prospective candidates. The question of whether or not such technologies “accurately” detect emotion or not is beside the point. What counts is that their verdicts are endorsed by the institutions which exercise coercive power over our everyday lives.

The work of Darwin and his successors currently provides both an essential theoretical basis and a powerful source of legitimation for today’s emotion analytics technologies. However, it is seldom recognized that Darwin’s theories were themselves, at their point of origin, bound up in the complex nexus of knowledge and power circulating around the possibilities of the 19th century’s revolutionary media form: photography. Darwin’s ideas about facial expression were fundamentally shaped by his experimental and illustrative use of the technology. Photography was a seemingly objective means of representation that was intimately bound up with the exercise of disciplinary power; today’s facial emotion analytics deploy a similar pretense of objectivity and reproduce the same sociopolitical blind spots.

Both emotions and facial expressions are durational, unfolding over an indefinite period of time. The photograph, however, tears the face away from this labile temporality, presenting it instead as a fixed spatial distribution of points and contours. In other words, Darwinian pathognomy could transform the face into a legible object only by reifying its mobile expressivity as a hard, static geometry. The ghost of physiognomy, it turns out, is not so easily exorcised.

In the mid-1870s, photography was still a revolutionary new technology working its way into the cultural mainstream. The Expression of the Emotions was one of the first books published in English to feature photographic illustrations, which Darwin insisted on despite his publisher’s warnings that they could make his text a loss-making enterprise. For Darwin, the illustrations afforded a degree of detail and objectivity that would have otherwise been impossible. Their tangibility and immediacy helped close the gap between his complex and sometimes counterintuitive arguments and the everyday visual experiences those arguments addressed.

Beyond this rhetorical function, photography also had an essential methodological role. As Darwin noted, “the study of Expression is difficult, owing to the movements being often extremely slight, and of a fleeting nature.” If the significance of a facial expression was to be found in fine details and brief muscle movements, then the observer must possess a quick eye and a supple memory to hold them together. Otherwise, the would-be analyst is trying to catch butterflies with their bare fingers. But photography could snatch this fluttering thing and cage it in a fraction of a second. It captures small and fleeting muscle contractions and isolates them from their eliciting context. The face could finally be addressed in its objective form, seemingly separated from the distorting effects of desire, memory, infatuation and imagination that attended earlier forms of reproduction.

Photography also addressed a more fundamental difficulty, which Darwin described as follows: “When we witness any deep emotion, our sympathy is so strongly excited, that close observation is forgotten or rendered almost impossible.” In other words, notwithstanding his attempts to play down the face’s communicative properties, Darwin acknowledges that facial expressions affect us in ways that make objective scrutiny extremely problematic. A face demands a response, whether of sympathy, horror, or disgust — a dynamic of reciprocity that contaminates objectivity. Moreover, he admits, we never encounter a face simply “as it is,” but in the context of “circumstances” that inescapably prime our understanding. The meaning of a face is determined by the interpersonal, social, and cultural conditions under which we encounter it.

The nagging question, from Darwin’s perspective, is this: If it is so difficult to separate facial expression from these dynamics of empathy, reciprocity, and sociality, then could it be the case that facial expressions are not simply atavistic reflexes but the necessarily historical and social products of human interaction? However, acknowledging this possibility would interfere with Darwin’s theory at a deep level. Once again, photography offered a way out of a seemingly irresolvable contradiction. By presenting the face as a static artifact trapped within a frame, the photograph seemingly isolated the face from its immediate socioaffective context, allowing Darwin to study it purely in terms of its material structure. Through photography, Darwin could frame emotion as a substance that exists “within” the face, waiting for the attentive physiologist to discover it. It is, of course, by the very same token that modern researchers believe they can mine emotion from the face as it appears in CCTV footage or webcam feeds.

You cannot have a face outside the workings of the implicitly social and political dynamics that have brought two or more bodies to be facing each other

Just as much as his predecessors (not to mention his successors), Darwin’s ideas about facial meaning were both constrained and enabled by the media through which he attempted to represent them. If physiognomy had been philosophy of the line drawing, the bust, and the silhouette; pathognomy would be a science of the photograph. However, at a time when the practice of photography required a significant degree of specialist skill and equipment, Darwin lacked the wherewithal to produce his own images. So he relied in part on the aforementioned Duchenne du Boulogne. The tormented face with which this essay began is based on one of the 84 photographs Duchenne included in Mechanism of Human Physiognomy (1862), which depicted various facial expressions supposedly characteristic of specific emotional states. His portfolio proved especially useful for Darwin, partly for its visual clarity and partly because he provided multiple images of the same subject (the old man pictured above) exhibiting various emotions, making the differences between them easier to identify.

As a would-be student of facial expression himself, Duchenne was up against much the same problems as Darwin. How to isolate a facial expression such that it becomes a legible object of analysis? How, furthermore, to extract it from the socioaffective context of the face-to-face encounter? Photography was part of the solution, but Duchenne also applied a further degree of technological ingenuity: a procedure he called “electrophysiology.” By stimulating muscles with electrodes attached to a subject’s face, he found that he could reproduce smiles, frowns, sneers, and a whole host of other stereotypical facial configurations. The procedure was noninvasive and supposedly largely painless, aside from the bizarre sensation of having one’s facial muscles manipulated by an external force.

Yet even as he deployed his French colleague’s images, Darwin was apparently intent on downplaying Duchenne’s technique. In the engraving above, the electrodes have been elided, which makes it appear as though the man is “spontaneously” displaying this look of mortal horror. In other instances when Darwin uses Duchenne’s original photographs, they are cropped to make the electrodes as inconspicuous as possible. If one looks at Duchenne’s original photographs, on the other hand, their grotesqueness becomes impossible to ignore. The electrodes make all facial expressions — even the ostensibly “positive” ones” — appear as tortures inflicted by disembodied hands.

Once we are familiar with Duchenne’s technique, we’re can understand the irony of the above image — a paradox Darwin made every effort to suppress. The individual upon whose face this “horrorstruck” expression was manifested was in all likelihood feeling nothing more than mild discomfort. In proving that stimulating specific muscles produces a given stereotyped facial expression, Duchenne severed the link between the facial muscles, emotion, and subjectivity in general — a gesture which Darwin would repeat, albeit more implicitly, with his argument that emotions and facial expressions are reflex responses.

The brutal spectacle of electrophysiology also demonstrates, by analogy, the coercive nature of photography per se. The pantomime of domination played out in Duchenne’s tableaux draws our attention to what Sara Ahmed describes as the structural “antagonism” of the face-to-face meeting. Ahmed argues that all face-to-face encounters, while not necessarily hostile, inescapably imply issues of negotiation, consent, propriety and power. These dynamics may begin as problems of etiquette but are implicated in the broadest sense in formations of gender, race, class, and social hierarchy — in questions of who looks and who is looked at.

To look someone in the face is to provoke conflict or request acquiescence; a claim or a pledge of intimacy; an offer of and a demand for surrender. It implies, asserts or establishes a relationship that it is our freedom to accept or reject in varying degrees. This is as true whether we are looking into the eyes of a beloved friend or (for whatever reason) staring at a stranger in the street. You cannot have a face outside the workings of the implicitly social and political dynamics that have brought two or more bodies to be facing each other — without, in Ahmed’s phrase, the whole sum of “that which allows the face to appear in the present.”

Insofar as it presents the face as a static object laid out for our scrutiny, photography can make it appear as if openness and legibility were simply the face’s essential properties rather than being the effect of a particular social relation. But Duchenne’s torture apparatus returns this submerged process to the image’s surface. Looking into one of his pictures, we can see clearly that the “readable” face is not a “found object” but the outcome of a complex, and coercive, artificial process. Similarly, the readings produced by today’s emotion analytic technologies are only the sharp end of a cascading sequence of complex social encounters. To understand the stakes in these moments of (mis)recognition, we have to unearth the submerged history of facial alignments that produced them.

Here the fact that Duchenne’s research was conducted upon institutionalized mental or neurological patients becomes extremely significant. The man whose image is reproduced in the Darwin woodcut was selected because he suffered from “a complicated anesthetic condition of the face” that allowed Duchenne to experiment on him without causing him pain — “as if I were working with a still irritable cadaver,” he said, adding that the man was “of too low intelligence or too poorly motivated to produce himself the expressions that I have produced artificially on his face.” Another of Duchenne’s favorite subjects was a 42-year-old man undergoing treatment for delirium tremens, a diagnostic forerunner of schizophrenia. These individuals were in no position to object to or resist Duchenne’s ministrations, let alone offer any kind of informed consent.

The liberty to disidentify with one’s own face has hitherto been, for some of us, an underappreciated dimension of freedom

Many of the most famous facial research projects of the 19th century were carried out on the institutionalized and the dispossessed. The anthropometric studies French policeman Alphonse Bertillon were carried out on detained criminals, as were Lombroso’s criminological studies and the “composite portraits” of Galton. Meanwhile, the photographer Hugh Welch Diamond took advantage of his position as chief psychiatrist of the Surrey County Asylum to catalog portraits of the mentally ill, a practice replicated at Paris’s famous Salpêtrière hospital by Jean-Martin Charcot and Albert Londe. The colonies were another ready source of “compliant” subjects, as, for instance, in the British government’s mammoth anthropological survey The People of India. Another crucial source for Darwin’s Expression was a questionnaire he circulated among the various scientists, adventurers, missionaries, administrators, and cops who peopled Britain’s global colonial outposts. Darwin does not give much thought to the circumstances under which their observations of the expressive behavior of the colonized peoples were recorded. The same might be said of contemporary data science researchers, and the social provenance of the images they feed into their algorithms.

In each case, coercive social relations bring the face before the camera. In this sense, the legible, objectified face which emerges in the 19th century is not only the effect of camera technology but also the developing power of what Foucault called the “disciplinary institutions” — prisons, factories, hospitals, asylums — to organize, rationalize, and instrumentalize the human body. The capacity of such institutions to isolate people, place them before the camera, and oblige them to expose their face as a static object produced the idea of emotion we’ve inherited: a physiological phenomenon inflicted on passive subjects by the outside world.

The ethical protocols of contemporary research into the human face are in some ways no less blurry. While participants in lab experiments are now required to provide informed consent, much of the latest technology relies on data uploaded to social media sites with no notion of what it might eventually be used for. The “disciplinary” logic of 19th-century photography reproduces itself explicitly in “emotion detection” applications, which, in virtually all their real-world uses, presuppose the unquestionable authority of those people or institutions (tech companies, border security, police, bosses) who will ultimately deliver the machine’s verdict on our faces, and thereby our souls. The liberty to disidentify with one’s own face — or at least, with what other people say about it — has hitherto been, for some of us, an underappreciated dimension of freedom. Soon, we may all be in a position to miss it.