Fascism is not aesthetic in its effects. The material suffering it seeks to perpetrate are in no way limited to surface appearances. The labor camps, border walls, wars of conquest, genocides, corporatocracies and prison societies the fascists dream of are nothing pretty.

But there is no question that style and aesthetics were important to fascist regimes. They were openly recognized by their leaders as such. The Nazis, as is often noted, paid a great deal of attention to their uniforms—although SS officers had to unbutton their famously good-looking trousers when they sat down because they were so poorly designed. Architect and artist Albert Speer was a central figure in the Reich (as onetime avant-garde Futurist Fillipo Marinetti was in fascist Italy), and though he mostly ripped off and deproletarianized an aesthetic developed in the USSR, the spectacles of fascist crowds that he orchestrated were glorified with worldwide attention through the work of another prominent Nazi, filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl. In Shōwa Japan, displays and declarations of devotion to the emperor helped unify a state otherwise riven by constant power struggles between monopoly capitalists, military higher-ups, and civil bureaucrats.

Today’s fascist style produces conditions of sufficient confusion, apathy, irony, or symbolic distance about what they are trying to do, so that they can fall within liberal democracies’ commitment to tolerance

Fascism appears in the midst of serious capitalist crisis and tries to solves it, like socialism, via organizing the masses. But unlike socialism, it uses the state to accelerate the power of the capitalist classes at the expense of designated scapegoats and “undesirables.” To make this approach to crisis palatable, fascism turns to aesthetics. Walter Benjamin, as Andrew Robinson notes in this article for Ceasefire, believed that “fascism logically leads to the aestheticizing of politics,” which marks a crucial step in fascism’s rise to power. “Politics is turned into the production of beauty, according to a certain aesthetic. This is achieved through an immense apparatus for the ‘production of ritual values.’” Instead of giving workers power over their lives, Benjamin argues, fascism gives them the feeling of empowerment through apparent self-expression in spectacle, through the vicarious experience of power in sublime aesthetic displays. Hence, for fascists to successfully capture power, they required subsuming the political under a monumentalist form of mass expression: massive parades, rallies, and other spectacular public events. Mussolini particularly favored soccer matches, while the Nazis looked to Roman imperial “bread and circus. But all these were necessary to produce the feeling of togetherness, participation, and empowerment that made everyday Aryans accept and even love fascism’s deepening of capitalist disempowerment.

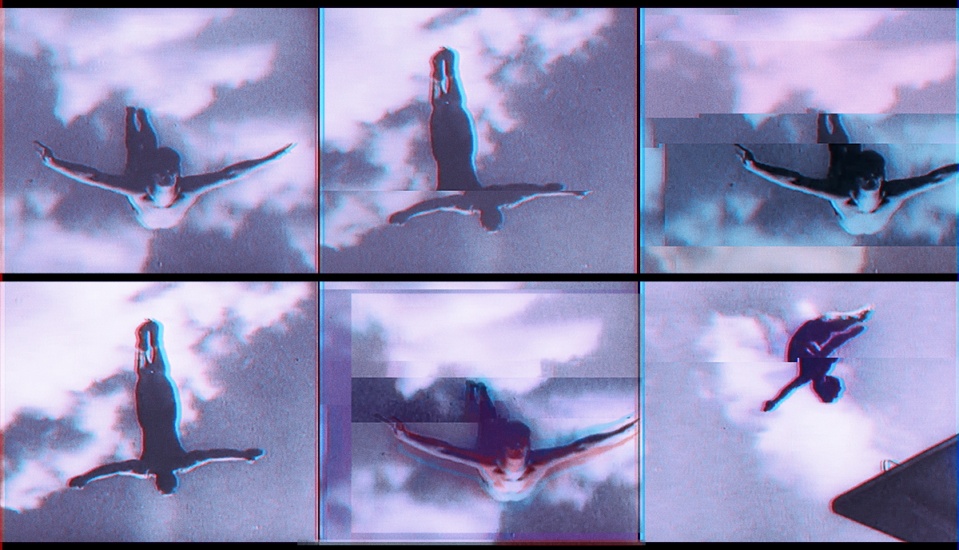

Though the fascists lost the war, their subsumption of politics to aesthetics — not a particular aesthetic of skull-head badges and torchlit parades, but a technique of aesthetics generally, the parade of beautiful and compelling images as political ends in themselves — has won the day. While the oppressive material realities of current regimes are becoming extensive and more overtly violent, those regimes draw from how fascism spearheaded the move to make us all think politics is just ideas, aesthetics, and symbols.

The Nazi propaganda machine is broadly understood, Robinson argues, “as a forerunner of the modern PR industry.” PR firms, marketing, infinite campaign financing, television, and the interplay of surveillance, algorithmic sorting, and targeted fake news (detailed in this Guardian report on “psychological warfare” firms like Cambridge Analytica) have largely reduced political participation in the U.S. to a twice-per-decade election ritual. Nothing better defines Trump’s appeal, nor Obama’s before it, than a feeling of finally being heard. Though Trump made some memorable campaign promises (the wall, the travel ban, etc.), he offered participation in an affect — despair where Obama once offered “hope” — more than he appealed with plausible political proposals. And the liberal reaction to the Trump presidency continues in this political mode. When liberals insist that the point of protest is to “have your voice be heard,” they are actually describing the fascist mode of political participation. To be satisfied with “feeling heard” in and of itself, as the goal of political activity, without pointing that expression toward building real material power, is to be a contented fascist subject.

But as a result of this shift from political to emotional participation, today’s fascists don’t need to make wholesale transformations in the scope and trappings of political spectacle that Mussolini and Hitler had to in the 1920s. Instead, they can rely on social media. While platforms like Facebook have been a crucial mode of social and political interaction for many, the way social media work to “give people a voice” and permit self-expression replicates this fascist subjectivity. Discourse via social media is just as ritualized, while the “listening” done by power is automated, pro forma, and reflected back to the user through the feed and the algorithmic “recognition” of the individual. Where the sniveling petty bourgeoisie of the 1930s saw themselves reflected back as Übermenschen under Speer’s spectacular gaze, now one can get the same feeling of participation in Trump’s tweet threads or through meme production.

That’s part of why the design motifs of contemporary fascism look as they do. There’s nothing about a red MAGA hat that makes you want to reach for art-historical antecedents; instead you’d probably think of a shopping-mall embroidery kiosk. Pepe the Frog is in the “lowbrow” comix tradition that takes its style through ironic re-rendering of mass-distribution techniques rather than attempts at the sublime. While traditional neo-Nazis for a long time gravitated toward hardcore and black-metal scenes, quasi-Aryan normcore-y EDM — as reproducible and repetitive as Pepe memes — has emerged as the actual anthemic music for alt-righters.

The inartistic, vernacular nature of these stylistic cues does not mean that contemporary fascism isn’t organizing its power through aesthetics. God Emperor Trump, red hats, Kek, Pepe, and the like evoke the aesthetic sensibility epitomized in Mussolini’s reign by the Me ne frego (“I don’t give a damn”) posters with which his party festooned the roads, cities, and countryside — an ironic sentiment that might not have been out of place among punks in 1977. They correspond with Trump’s buffoonish attempts at appearing serious, which are a crucial aspect of his relatability as an everyman. The fundamental mundanity of the alt-right aesthetic is a crucial part of its power, just as slick sublimity was central to the power of their fascist predecessors in the 1930s.

Contemporary fascism faces a very different world than the Übermensch of yesteryear, and a different sort of potential convert to target. In the early 20th century, Nazis could seek to persuade traumatized World War I veterans desperate to make sense of the senseless imperial carnage they had lived through that there is beauty and vindication in further war and destruction. They needed to win adherents away from the thriving political alternative of socialism, and it was only in the wake of failed socialist revolutions that fascism rose in Europe. Fascist aesthetics offer the middle classes and petty bourgeoisie a simulacrum of the unity and power that workers actually but temporarily achieve when they rise up. But rather than organizing grassroots power, fascism reduces it. The fascist state asks the population to sacrifice their political will and ability to control their lives to the Party in exchange for the exhilarating feeling of unity and power: a feeling usually achieved through the exile and murder of the internal “Other” — the Jew, the indigene, the queer, the communist, the Black person, the Muslim.

Fascist aesthetics offer the petty bourgeoisie a simulacrum of the unity and power that workers actually achieve when they rise up. But rather than organizing grassroots power, fascism reduces it

Fascism produces an ever more policed, ever more hierarchic society since it reduces the scope and purview of people’s daily lives, even those within the party, reproducing the conditions of colonialism within the population of “citizens,” but it offers up limitless symbolic power in exchange. Thus fascism’s relationship to a mass movement is crucially and centrally a symbolic one: Both Hitler and Mussolini bumble into control much more than they rise on the backs of a mass movement. As feckless liberals abdicate power in the hopes that it will somehow “reveal” the true nature of fascism — think of Democrats relying on Trump to finally demonstrate his unfitness to rule rather than organizing an actual opposition — fascism consolidates representations of that unfitness as opportunities to demonstrate loyalty and belonging.

Today’s Nazis, unlike those of the 1920s and ’30s, are not primarily addressing people who have experienced the hardships of war and are suffering its lingering aftereffects, but well-off white boys who have long enjoyed the spectacle of aestheticized war in the form of boredom-abating video games. (See, for instance this.) While the militia, patriot, and survivalist far-right movements continue to draw their base from rural middle-class landowners, police, and veterans, the alt-right appeals to a younger more urban group of boys. Their alienation derives from the anomie of contemporary global capitalism in terminal crisis, with scant hint of an organized “left” alternative to its hegemony, and their enemies are not the USSR but the “politically correct” who might interrupt their self-satisfaction and the supposed specter of “white genocide.” They liken their resistance to these as a kind of punk rebellion.

Fascists emerge today as the middle classes witness the global collapse of capitalist profitability and the ecological collapse of the world itself. But rather than see those collapses as intrinsic to white-supremacist cisheteropatriarchal capitalism in the first place and trying to imagine a better world — as the increasingly large group of radicals and revolutionaries do — and rather than flounder in despair and guilt as the liberals do, the fascists double down on the system. They call on straight white Christians to band together and make sure they survive this coming collapse, to decide who survives and stabilize the system through an ocean of blood.

But the ocean of blood has limited appeal as a selling point. Perhaps the most crucial difference between fascist aesthetics now and then is that Nazism remains prominent in shared cultural memory as the boogeyman. Nazism has been represented within liberal democracies as a grossly special and unprecedented evil, a massive historical anomaly and definitely not the continuation of settler colonialism within the European continent that it actually was, as Aimé Césaire argued in Discourse on Colonialism. The constructed uniqueness of Nazi evil allows white-supremacist settler colonialism (of which Nazism was just one particularly extreme example) to flourish, but it also makes it hard to be a straight-up Nazi in hopes of openly encouraging that flourishing.

Thus, today’s fascist style must concern itself not with aestheticizing the political as such — that’s already been accomplished after all — but instead must work to produce conditions of sufficient confusion, apathy, irony, or symbolic distance about what they are trying to do, so that they can fall within liberal democracies’ commitment to tolerance. This also allows them to not repel potential converts with trappings (swastikas, SS memorabilia) that might cost them social approval.

The social unacceptability of Nazism makes straightforwardly embracing its symbols and aesthetics an efficient way of expressing social alienation or the rejection of liberal society (à la Charles Manson, or 1977 punks), but it makes them useless for expanding the ranks of fascists among polite circles. Modern fascists and neo-Nazis have relied on intricate layers of esoteric symbolism — flags, group logos, band names, and an assortment of Nordic and neo-pagan spiritual languages — to identify each other in public without getting the shit kicked out of them. The alt-right has adopted this proclivity for esoteric symbology — Pepe’s finger gesture being the most consistent — but it has also developed a more accessible aesthetics, as befits an online movement that thrives on virality. Contemporary fascist images have to be mass-produced and easily reproducible to give the form of participation and enjoyment that keeps their message and movement alive. They rely on similar principles as what Hito Steyerl calls “poor images” do. Like “poor images” — low-resolution digital images that are thereby easier to circulate and adulterate — fascist tropes only function or make meaning when in constant circulation, and are adapted formally to that purpose.

Euphemistic images like Pepe and Kek short-circuit the sublime, and with it the attempt among the commentariat to interpret the tokens for deeper meaning — it is what it is

So the memetic and anonymous nature of fascist image production becomes paramount. There are no Albert Speer in the alt-right. Individual creativity is surrendered to the crowd, the mass, in exchange for a perception of powerful group cohesion. Their memes are often marked by a slapdash, cut-and-paste aesthetic — tactics of the “poor image” directed to totalitarian aims — which, again, like Trump’s clumsy braggadocio, is precisely what makes them appear accessible and populist.

This, in turn, is crucial to their ability to contribute to the formation of a mass-fascist subject. Some contemporary fascists of course use swastikas and are very explicit in their project. They require no euphemisms to enact racist violence in the name of their movements, and examples abound of this explicit terror being committed under the banner of literal Nazi symbols. Parallel to this, however, there is a more euphemistic thread that attempts to flourish even where such obvious bigotry is unspeakable. Within this thread, fascist symbols don’t explicitly point back to the projects of racism, patriarchy, anti-Semitism, and genocide that fascism ultimately aims at, because those projects flourish under liberal democracy mainly by remaining unspeakable, disavowable. For fascism to spread its messaging and bring in uncommitted “apolitical” white boys who might otherwise be turned off by outright Nazism, far-right memetic and euphemistic images like Pepe and Kek circulate among otherwise nonpolitical shitposting, jokes, and trolling. These short-circuit the sublime, and with it the attempt among the commentariat to interpret the tokens for deeper meaning. The slovenliness enforces an object’s status as self-referential, tautological — it is what it is.

In this sense, the more ripe with meaning an image is — the more aesthetically compelling or intricate or historically burdened it is — the less likely it is to work for these purposes. If liberalism hides the ongoing practice of settler colonialism behind Enlightenment principles and rights discourses, fascism chooses flimsier, uglier masks, in hopes that the day will soon come when masks will no longer be necessary.

There is nothing inherently fascistic about anonymous or crowd production, or in the dissemination of “poor images.” This approach, which has analogues in punk, zines, and other forms of DIY culture, has been adopted at different times across the political spectrum, to generate a sense of collectivity and anyone-can-do-this empowerment. It is the mass (re)production of familiar styles, aimed at proliferating a euphemistic alibi for fascist terror, that marks a particular mode for modern-day fascist aesthetics.

Fascism cannot spread on the level of discourse, or advocacy. It can spread only through its own inertial power, by becoming a kind of common sense. Fascism is, after all, the common sense of settler-colonial capitalism, stripped of any concession to the nonwhite or the working classes. The dissemination of euphemism, esoterica, and hidden-in-plain-sight symbolic violence helps jam the gears of a liberal mind and institutions that are unwilling to act “without evidence.” This ends up leading to misguided demands that fascists be given room to speak so that their ideas can be “debated.”

Among the cis white boys increasingly “left out” of a collapsing economic, ecological, and political order fascism finds its fertile ground. The end of this world as we know it means their future holds one of two things: the revolutionary abolition of their subject position (and thus, their white male supremacy such as it exists now) or doubling down on identification with that “lost” supremacy while hoping that fascism materializes their sacrifice of political agency as actual power. That bet has always been a bad one, but the prejudicial violence it requires has never been enough to disqualify it and make it unthinkable. It’s up to us to prove to each of them just how bad a bet it is.