We wasn’t supposed to make it past 25

Joke’s on you, we still alive

—Kanye West, “We Don’t Care”

Around the same time porn was brought into the American home via cable television and videocassettes, President Ronald Reagan was obsessing over family values as the urtext for American values. Obviously, this ideal family was white, middle-class, and nuclear, and he viciously attacked everything that did not fit into this model. During his runs for Republican nomination in the late 1970s and early 1980s, he deployed the trope of the “Welfare Queen,” the young, black, single mother who not only drained government resources through fraud but also ruined the potential of all black people by bad parenting and neglect. This figure — not an adult or a mother but a “Queen” — transgresses domestic respectability in an effort to feed her family, work outside the home, and, heaven forbid, find some pleasure.

Following Darine Stern’s solo cover of Playboy in 1971 — a first for a black woman and three years before Vogue — this era did not take pornography to be a metaphor. But today, porn — or rather, the pornographic — is not tout court considered a four-letter word in the same way it was during this period of moral panic. In “How to Look at Pornography,” (1998) Laura Kipnis writes that the medium “exposes the culture to itself. Pornography is the royal road to the cultural psyche.” The contemporary omnipresence of porn aesthetics on social media — on Instagram, captioned food porn or on YouTube, “style haul” videos — has bred a voyeuristic practice of looking. For unlike with the analog tape formats of the 1970s, 21st-century adult-only material is no longer chained within four walls; it moves with you in your pocket, with a relentless possibility of scrolling. Anti-pornography doesn’t always designate pro-family but when it does, it really does. Even if the black family does not exist tangibly as Reagan would have it, black memes often cite or allude to the family — even by way of the absence of any family in the images. On Instagram, hashtags such as #ballerbabies, #blackbabies, #blackowned, #blackbloggers or even #blackpower are metonyms for the black family trope even without the full representation of kin or household. Pictures of daintily decorated Easter eggs or kids posing alone in ankara print fabrics signal a stable optics of care, the domestic dream.

Respectability, mired in adulthood, is more for the living than the dead

Charges of black familial deviance are often counteracted through the rigid force of respectability — doing the right thing. On the one hand, hypervisible black internet culture does not genuinely bow down to the logics of respectability but rather display a kind of ratchet refusal. Kayla Newman’s brilliant black vernacular innovation (“We in this bitch. Finna get crunk. Eyebrows on fleek. Da fuq.”) or NeNe Leakes’s routine drags on Twitter do not fit into the historical account of Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham’s classic 1994 study of how black Baptist women mobilized the “politics of respectability” to fight racism and sexism. And yet the very circulation of what Aria Dean and Lauren Michele Jackson have written about as the blackness of memes refer to respectability even as they have the air of denying it. Black culture is admired, commodified, and appropriated in part because non-black people can consume disrepectability in temporary abandon without messing with their criminal record, credit, or stable employment. On the other hand, the way respectable black adult couplings like Jay Z and Beyonce are mobilized online spur the celebration of #blacklove in media res.

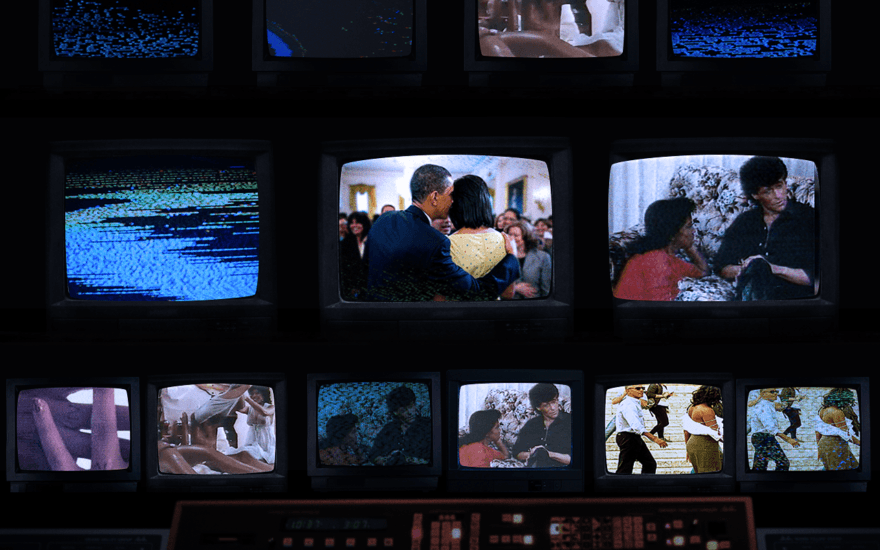

The image of President Barack Obama, who ordered the drone strikes that killed between 384 and 807 “civilians” during his two terms, only counting those in Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen, now satisfies a nostalgia for a past that never was; liberals remember Obama not as state-sanctioned murderer but as his Instagram and Twitter bios read, not only “President” but also “father,” “husband,” and “citizen” — all markers of proper adulthood. The Obamas are in their own league of Family Goals. A March 24th tweet by @barackobama about March for Our Lives reads, “Michelle and I are so inspired by all the young people who made today’s marches happen. Keep at it. You’re leading us forward. Nothing can stand in the way of millions of voices calling for change.” As the nation’s proud dad, he’s no longer a symbolic patriarch but he is, galvanizing his status as male head of the family, still a literal one. You can almost see the headline. Former Presidents: They’re Just Like Us!

Michelle stands in as a stand-in, a representative of respectable black motherhood, portrayed in the softened emojis of social media reactions. In 2011, Barack called Michelle “his rock” in an interview with Oprah, everybody’s Mammy, fossilizing Michelle as Mom. In public, the figure of the black mother is filtered through a Madonna-whore complex. She takes from the world through welfare or mothers the world through moral servitude. With the Obamas as the poster couple, what is otherwise critiqued through the lens of emotional labor is sanitized and celebrated as a form of resistance, an index of optimism against racial terror. Everyone gets in on it: The #blacklove hashtag is saccharine and stylized. A constantly updated and endless stream of romantic performance, black adulthood performed by everyday users becomes framed as black power lite. Gay and straight couples, smiling wide while flaunting their home-cooked meals, ultrasound videos, and professional photoshoots. Show them you’re good, clean, pure, and moral, even if you aren’t or you shouldn’t have to be.

The 1984 all-black adult film, Black Taboo, directed by a white woman, is the story of a family’s erotic joy over the eldest son, Sonny, returning from the Vietnam War, marking the mundanity of black perversion. While the family celebrate — through fucking each other — Sonny himself suffers from symptoms of post-traumatic stress, and can only truly relate to Jodi, an inflatable doll who was his lady-in-waiting in Vietnam. While critics such as Laura Kipnis often think about porn as a genre that transgresses boundaries, it is also worth noting that porn as an aesthetic system is not automatically transgressive, and also buttresses middle-class family norms, in this case, infantilizing the black man, whether we take it as a joke or not: An adult toy, a sex toy, is still, after all, a toy. By subbing “black” for what is known in the anthropology of kinship as the “incest taboo,” Black Taboo exposes how blackness is taboo.

In an attempt to counteract the narrative in which the slain black man is remembered as a “thug” (recall the protest to the New York Times calling Michael Brown “no angel” in 2014), Stephon Clark, who was shot at 20 times and murdered by Sacramento police in March, is being remembered as a father: candidly sleeping on the couch holding his children or in a formal family portrait his children and their mother. You shouldn’t have to be a “family man” in order to avoid getting slaughtered by the U.S. militia, also known as the cops. The collective shuffle of self-representation of the black family attests to the general attempt to recover the humanity and subjectivity of the desecrated, murdered, and neglected black figure.

In this publication in 2016, Aria Dean wrote about how videos documenting black death exist in tandem with what we call memes, those amusing bite-sized morsels, like chocolate that melts in your mouth. Through this rub, Dean insists that “black death and black joy are pinned to each other by the white gaze.” Both memes and black death videos, in other words, tilt toward the pornographic. Both mark what Saidiya Hartman might call “the trace of dispossessed lives.” Respectability, mired in adulthood, is more for the living than the dead.

Just as for Reagan the only family was the white nuclear family, to aspire towards adulthood online is to desire a certain kind of adulthood

For black people, it is often suggested that becoming an adult is a death wish. “Black adulthood” is a vexed category involving premature death, incarceration, state surveillance, abysmal medical care, environmental poison, no wealth, no jobs, no future. But you don’t have to be a card-carrying afro-pessimist to take stock of the narratives of social negation that riddle black life. As racial terror imbricates with erotics, the circulation of black death on camera is pornographic, framed alongside dance videos, looped remixes, and Rihanna collages. Whether or not repeated viewings of police shootings elicit shock, whether or not we are desensitized to violence on screen, whether or not it moves a mass to gather in the streets, the pleasure and violence of looking must be understood together. A hardly benign internet term like “adulting,” which refers to traditional grown-up accoutrements like bills, mortgages, and full-time jobs, is disrupted when placed alongside blackness.

Just as for Reagan the only family was the white nuclear family, to aspire towards adulthood online is to desire a certain kind of adulthood, one involving unbridled submission to neoliberalism, the state’s logic, and a dated middle-class Boomer vision no longer materially available to Millennials. There would be nothing more daft than an adulting meme, which digests like a party favor, taking stock of the kind of surveillance and violence black populations are subject to. The late Stephon Clark’s aunt, Shernita Crosby, critiqued the citation of her nephew’s criminal record, saying, “If anyone wants to ridicule his past … thank you very much to society for making him grow up too fast.”

At the same time that black adulthood is doomed, black childhood — because of the ways vulnerability is systematically both denied and weaponized by the state — is oxymoronic. Due to unevenly harsh discipline in schools, vehement disregard for black innocence, highly disproportionate likelihood of being arrested and incarcerated, and forced sterilization, “In America, black children don’t get to be children.” So states a 2014 Washington Post headline. The author of the newspaper’s op-ed, black journalist Stacey Patton, writes:

If a white life cycle features innocence, growth, civility, responsibility and becoming an adult, blackness is characterized as the inversion of that. Not only are black children cast as adults but, just as perversely, black adults are stuck in a limbo of childhood, viewed as irresponsible, uncivil, criminal, innately inferior. Through the incarceration of black adults and the disproportionate placement of black children into foster care, the state acts as a parent, while simultaneously abdicating its responsibility to invest in children of color.

Adulthood has long existed as a fraught index for black Americans’ relationship to, and entryway into, humanity and citizenship. Since even before the end of de jure slavery, access to freedom has meant access to some warped signifier of adulthood. For the purpose of congressional representation, for example, the Compromise of 1787 set up a ratio of exactly how much slaves — of any age — would count in relation to a free adult white person: three-fifths. And after so-called emancipation, infantilization has remained a racist strategy, insisting on the inferiority and sub-humanity of racialized people in everyday social interactions such as hair-touching, back-patting, looking down on, or in the persistent representation of legal adults as children unable to take care of themselves and thus in need of surveillance and punishment.

The black family is always already perverse, marking taboo, in part because it lacks adults. The black family lacks adults not only because state imposes violent techniques of inferiorization but also due to the persistent myth of absent parents. Beneath the headlines, stories like these uphold stabilized ideas of human development under neoliberalism by wanting to ensure that black kids, too, have access to the entangled myths of childhood and adulthood: As though it’s only fair that black people, too, are submitted to a childhood realm where we have all the imagination in the world but no agency, and school is a dead-end job; or that as adults, black people get a right of entry to mind-numbing nine-to-five jobs, car payments, debilitating debt, and a loveless, sexless state marriage. Unlike the politics of respectability would have you believe, black social life is urgent and insurgent when it disrespects the strictures of an imagined middle class family, spatialized as some impossible halfway.

The adult film is more than just for adults, but it is also about solidifying what adulthood means in relation to the geography of the household

In other words, black adulthood stinks. On the one hand, these are aspirations for black bourgeois respectability politics and, on the other, adulthood is a tool of state warfare enlisted to further criminalize, demonize, and destroy black life. Both of these positions, however unequal, rely on the policing of what constitutes the normative and what constitutes the taboo.

Racism doesn’t care how much money you have. A recent study called “The Equality of Opportunity Project,” conducted by researchers at Stanford, Harvard and the Census Bureau exposed what some of us already know because we live it. “White boys who grow up rich are likely to remain that way, “ the co-authors of a New York Times article explained about the study “Black boys raised at the top, however, are more likely to become poor than to stay wealthy in their own adult households.” The study wasn’t really about black boys but what black children are supposed to become: adults. It is another version of Stacey Patton’s “Black Benjamin Button” theory.

While the question of how wealthy people stay wealthy is less important than how poor people might be granted a living, the subtext here is that racism is so vile that even rich kids — albeit black — cannot stay rich and become rich adults. But how long will we mourn the attainment of wealth, homeownership, before we say fuck it altogether? Can black folks afford to refuse the norms of adulthood and instead, somehow, claim the taboos already assigned to us? If thinking about adulthood requires thinking about the family, we then must also think about those family forms that never reach normative family status. To claim the taboo would contradict most of the claims for black personhood since antebellum and in the present moment. The American pornographic, as a genre and a way of looking, is at the core of blackness’s violent origins: It is its history, its present, its frontier. Hovering at the edge of the possible and the impossible, the pornographic is a breaking point worth breaking in. If, as Saidiya Hartman maintains, “slavery is the ghost in the machine of kinship,” it is also true that the black family — its making, unmaking, and impossibility — is the ghost in the machine of adulthood.

Being an adult is an impossible achievement under capitalism, especially if we stick to the standards set by the Boomers: homeownership, social security, good credit score, a stable job, having toilet paper in bulk, marriage, paying bills, and overall being financially independent. While it might be easy to brush off neoliberal how-tos on “adulting,” almost all those above standards have immense and serious effects on black people, especially when we think about how they interact with what Michel Foucault powerfully coined as the “carceral continuum,” that is, the wide-ranging ways the prison industry diffuses itself to enact systems of social control and discipline, ranging from school and debt collection to domestic violence calls.

It has become customary to say that almost everything, including adulthood, is socially constructed. Less commonplace is to detail how, by whom, when, where, and why adulthood is constructed. Even as child labor laws in England — under the name of Factory Acts — were being passed in the 19th century, elsewhere in the colonies and in the Americas there were no such notions of childhood for what the intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois has called the “darker races.”

If “slavery is the ghost in the machine of kinship,” the black family — its making, unmaking, and impossibility — is the ghost in the machine of adulthood

The black American family has been at once the site of pathologization, politicization, and surveillance in its refusal of the nuclear form. In The Negro Family: The Case For National Action of 1965, better known as the Moynihan Report, poor black single mothers were pathologized for their “ghetto” ways, rendered the taint of malignant matriarchy with roots in slavery. This “impossible domestic,” to borrow from Fred Moten, is well known by scholars, pop culture consumers, and social media users alike. Black women have been mothering white children for centuries and yet are deemed incapable of raising black ones.

The Silver Age of ’80s pornographic films — usually considered an era less historically notable than the Golden Age’s mainstreaming of “porno chic” in the ’70s through films such as 1972’s Deep Throat — offers us insight into a medium through which adulthood is constructed and where the myths of adulthood and childhood alike are racialized. The U.S. release of VHS in 1977 suddenly made porn cheaper, faster to produce, more varied, and more intimate. The domestic imaginary — both called on and rejected in the pornographic image — now became doubly referred to through both content and viewing location, like in the aforementioned Black Taboo, as well as Let Me Tell Ya ’bout Black Chicks (1984), Black Throat (1985), or Guess Who Came At Dinner (1987). Porn was in your home and the home was in your porn. The adult film is more than just for adults, as in restricted from children, but it is also about solidifying what adulthood means in relation to the geography of the household. Do we keep the porn cassettes in that secret hiding place next to the guns? Do we watch porn together on the couch? Does the (white) man of the house keep his all-black or interracial porn in his sock drawer, away from prying eyes?

In her 2014 book, The Black Body in Ecstasy: Reading Race, Reading Pornography, Jennifer Christine Nash argues that racialized porn films from the 1970s and 1980s can be read to reveal agency and desire in black female subjects. For Nash, pornography does not provide an answer to the anti-porn feminist legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon’s question “What do men want?” but instead to the question “How do women resist?” As a post-Lil’ Kim black feminist, Nash’s argument is not in line with MacKinnon, who has famously argued that pornography is oppression and sex is not pleasure. Nash uses the film Black Taboo to think about the intimate links between pornography and comedy, zeroing in on the ways the black woman protagonists comedically play with racial fictions and sexual norms. Focusing on the labor and practice of the black woman performer, Nash departs from black feminists, such as Alice Walker, who rhetoricize pornography, following MacKinnon’s dictum that pleasure can operate as the “velvet glove on the iron fist of domination.” In “Civil Rights Against Pornography” (first published as “Pornography as Sex Discrimination”), MacKinnon presents a taxonomy of racialized and othered pornographic figures. “Asian women,” “black women,” “Jewish women, “amputees,” “retarded girls,” and “so-called lesbians” all proffer the pornographic screen their own scandalized sexual spin on racist tropes. In this passage, the white woman is not subject to race; she is the unmarked adult, coming to supplement the “adult woman” subject to becoming a child. Here, MacKinnon does not admit that we are all racialized, that race exists in relation, even as she writes, in the same essay, that in porn “Black women play plantation, struggling against their bonds… Adult women are infantilized as children, children are adult women, interchangeably fusing vulnerability with sluttish eagerness said to be natural to women of all ages, beginning at age one.”

Images of black families and the contrivance of black love online are trapped in respectability politics, circumscribed by the meetings of class, race, and gender. An acknowledgement that race fucks with normative adulthoods allows for an acknowledgement of how adulthood fucks us. Our biggest fears and truest fantasies are realized online. In Algorithms of Oppression, Safiya Noble studies how — like the world we live in because it is the world we live in — algorithms are racist. In recent memory, if you typed “black girls” into the bar of a commercial search engine, your top hit was a porn site. To spell it out: all the adults are white, all the black girls are porn, but some of us are black women.

This essay is part of a collection on the theme of ADULTHOOD. Also from this week, Rachel Giese on kid heroics, and Hanif Abdurraqib on the aesthetics of being old.