NEW FEELINGS is a column devoted to the desires, moods, pathologies, and identifications that rarely had names before digital media. Read the other installments here.

When my iPhone’s battery life finally withered to less than the length of time it takes to break a sweat, I decided it was time to get it looked at. I live on a small island more than an hour’s drive and a ferry ride from the closest Genius Bar, so I settled for a kiosk at a nearby one-storey mall, handing my cell phone over to a kid with a patina of facial hair so blonde and newborn it seemed to waver in and out of existence, like an aura kicking off a migraine. As he thumbed through my settings and apps, I told myself: It’s like getting naked at the doctor. He’s a professional. I’m sure he’s seen it all.

As he thumbed through my settings and apps, I told myself: It’s like getting naked at the doctor. He’s a professional. I’m sure he’s seen it all

“Woah. Do you know how many tabs you have open? There’s, like, hundreds.” He turned the screen to show me a cascade of web pages running backward through time like a chain of succession — a desperate quest for some original source.

“That’s probably what’s burning your battery, but let me just check a couple more things.” He turned back to the phone. “The Best Keto Gluten-Free Sandwich Bread!” announced itself from the top of my shameful tab pile-up.

“I’m not on a keto diet,” I felt the need to say, “I just eat weird things.”

Here is something I’ve been made to understand: Using my phone and computer might feel like nothing more than the static of passing time, but all the micro-decisions I make as I search and swipe and scroll are secretly valuable commodities. Every time I touch a device, I leave a trail of digital DNA that can be used to reverse-engineer some version of me that is used to sell me things.

It’s not that I don’t believe this — it’s just that my belief is an act of will. Understanding myself as data requires a large measure of abstraction, so when I think about how my data is used and by whom, I would say it makes me feel abstractly very bothered. Theoretically totally creeped out. Vaguely over-exposed.

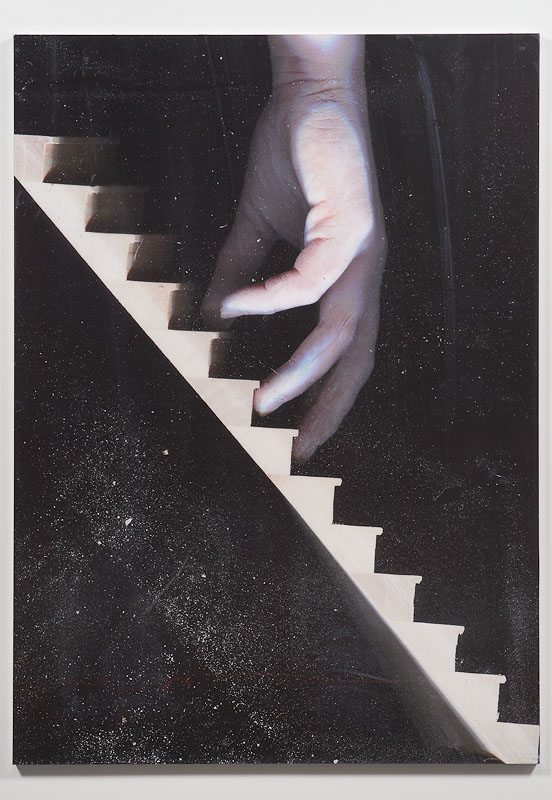

I don’t like to think I’m possessive, but the internal histaminic explosion I feel when someone else uses or even just touches my devices says otherwise

Let me tell you what feels definitely and unbearably concrete: some post-teen getting his paws on my phone and riffling through my tabs. My husband hopping on my computer because it’s close by, and he wants to “just check something really quick.” When he does this, I have to suppress the urge to body-check him and make an offer that’s really a demand: let me do it. I don’t like to think of my relationship to technology as possessive, but the internal histaminic explosion I feel when someone else uses — or, if I’m being honest, even just touches — my devices says otherwise.

There’s nothing on my phone or computer that could be considered even remotely indecent. If you went to my photo roll looking for nudes, the closest you’d find is a visual diary of chin acne blooming and receding like crops in rotation. In my Notes App, the most telling thing you’d uncover are some cringey artifacts of stoner-think nestled among the grocery lists. (“Every moment is a new country and everyone is an ambassador.”)

That’s about the worst of it. From there, it only gets stupider or more mystifying: a full 20 minutes of footage of me sitting at my desk and typing, an album of screenshots from the weather network, 17 photos of a plume of smoke, bookmarked websites devoted to pseudoscience and reality TV and ghosts, two different audio recordings of water sloshing twangily in a metal bottle.

There is a context for each of these. But there is no one explanatory key to unlock the cryptic, boring mess of the whole. For everything that lives on my computer and phone, the only common denominator, really, is me.

Something I’ve noticed in my Instagram feed lately: the influencers seem exhausted. Many of the big accounts I follow have pivoted away from producing the best content and towards debunking their own stylization, offering glimpses of the labor and self-doubt that churns beneath what might otherwise seem glossy or enviable. “Here’s what you don’t see,” one caption begins; “A year ago, I never would have shown you this,” says another, as these users crack open their phones and sample from the would-be refuse.

It’s not like leveraging authenticity is a new thing, but what strikes me about this version of the trend is how much explanation the smallest acts of self-conscious unraveling involve. The caption-to-photo ratio is off the charts. It takes a whole essay to comfortably give up some of the rough work it takes to be a person.

As long as I have a device on hand to help me do nothing, I’m always at work in my inertia, mounting evidence of myself

Thinking of yourself as a product of your interests and relationships is one thing, but digital traceability foregrounds the fact that you’re also formed by more aimless habits and tendencies. My phone and computer are repositories for the minutiae that swims through my stream of consciousness: what I wonder about, worry over, linger on. Curiosities I would have once called “idle,” fancies I’d dismiss as “passing” — it seems there’s no longer such a thing. As long as I have a device on hand to help me do nothing, I’m always at work in my inertia, mounting evidence of myself.

The kinds of digital particulates and residues that turn up in our devices aren’t the things we might normally stake our identities on, but the fact of their being recorded imbues them with new meaning. It’s like finding out you’ve been talking in your sleep — awful and embarrassing, but also fascinating. Of course you want to know what you’ve been saying. And there’s the potential for a kind of pay-off: having been exposed to parts of yourself you might otherwise have dismissed or forgotten, you can share that composite on your own terms by with others. It can feel more “real” to reveal yourself through charming idiosyncrasies than through more concrete taste-markers.

When I’m feeling generous, I read the minor riot of imperfections in my Instagram feed as a heartfelt backlash against the toll it takes to both produce and consume mediated lives. More cynically, I might call it a race to vulnerability in the new competitive landscape of monetized self-exposure. Either way, I get where the impulse comes from — I indulged it only a few paragraphs ago. It’s not like I’m really showing you all the curiously boring stuff that’s in my phone; I’m only telling you about it. And I’m making sure you know that I know how boring it is, before you reach your own judgments.

One thing the era of big data teaches is that everyone has something to hide. My blind-spots are witnessed by some algorithmic omniscience that uses them to reconstitute me as a consumer. Weirdly, allowing a human being access to that same material feels somehow more uncomfortably intimate, even if I know it’s less harmful. Because knowing you’re being monitored is different than feeling seen. Differently put: I’m more willing to be exploited than I am to be judged. That itchiness I get when someone touches my phone or computer is a kind of frantic impulse to explain: I want to gloss on the content, either to laugh it off or provide its rationale. To annotate my own banal, unmemorable, totally decent exposure. Just let me do it.

Here’s something I’ve been wondering: Why keep all these things if they make me feel so vulnerable to misunderstanding? I’m not someone who has their phone with them all the time, but I do have a deep documentary impulse, and I save more of the nonsense I accrue on my technology than is useful. Because, though it feels wrong to say so, I do truly recognize myself in my devices. And I am self-involved and nostalgic enough to enjoy the feeling that brings: of being reminded, unlocking the mess, providing the context. Despite my better knowledge, my devices still feel like private spaces.