Art fairs give me anxiety. To look at hundreds if not thousands of artworks at once means little more than a superficial scan of volumes of visual data, sounds, themes, voices and stories, all begging for your attention or screaming their intentions at you. It is a surreal, sensory overstimulation. Surreal, because in one corner, for instance, you see a giant white body of a snake on which people with virtual reality glasses strapped to their faces are sitting, necks cranked inharmoniously like owls in trance. This was last year’s Frieze art fair, and the snake, Jon Rafman’s Transdimensional Serpent, was set in a luminous yellow booth of Seventeen Gallery. If surrealism is the displacement of the ordinary in an extraordinary situation, one look at the works of artists in the immersive, digital sphere and you’ll find an uncanny surreal vernacular.

Like a snake, the digital is swift, vigorously morphing or shedding old skin, discarding old versions for a new slick adaptation, consuming subjects whole that are seemingly inconsumable, basking on the open rocks or crawling into deep crevices, or all at once. Unlike an ophidian, the digital is nonlinear, expanding like a rhizome, growing in all directions and with little need for anything other than itself to feed on — a living ouroboros. In this discursive paradigm, the line between real and unreality, the spirited and the dead, is thinned and redrawn.

The Biblical serpent, having condemned us to our desire, remains a sacred reminder of our vices. George Bataille identifies the human taste for fatalism: We are not just a curious animal, but an animal attracted to death and destruction to dangerous degrees. “What we have been waiting for all our lives is this disordering of the order that suffocates us. Some object should be destroyed in this disordering … We gravitate to the negation of that limit of death, which fascinates like light,” he writes in The Cruel Practice of Art (1949). In his view, we have a primordial dissatisfaction with “normalcy” and are bored with the natural cycle of life, which lends the imagination many alternative realities, giving us something to live and die for, and summoning parallel universes where these scenarios exist. “Only a few of us, amid the great fabrications of society, hang on to our really childish reactions, still wonder naively what we are doing on the earth and what sort of joke is being played on us.” The desire remains to “decipher skies and paintings, go behind these starry backgrounds or these painted canvases and, like kids trying to find a gap in a fence, try to look through the cracks in the world.”

The surreal punctures the familiar; so we look for fissures, and if we don’t find any, we contrive them into existence

In her “morphological” essay “The Skin of the Dead: Shrouds, Screens, Ectoplasms” on Christian iconography of the hereafter — the material traces left behind by the departed and the difficulty of imagining what remains of the living — anthropologist Christine Bergé describes this magical ideation: “The image-screen painted by the artists becomes a window through which one looks, and that looks out over the landscapes beyond … Presences emanate from the surface, unfold and penetrate the floating gaze of the contemplator.” And then we are transfixed: “The painting becomes an open window on a virtual world … Each shadow of the picture becomes a fold that contains its treasure to discover. From the bottom of the canvas arise glances, the creatures enclosed in the threads of the canvas begin to free themselves.” And so we look for fissures — for the surreal — and if we don’t find any, we contrive them into existence. An existence that, for some, corresponds less and less to a warm-blooded body.

The surreal is unsettling because it is almost real, behaving unrealistically. It punctures the familiar while operating strangely, uncannily. And in a ravenously accelerated shedding and shifting process, digital art liberates surrealist aesthetics, providing technologies to incorporate objects in abject spaces.

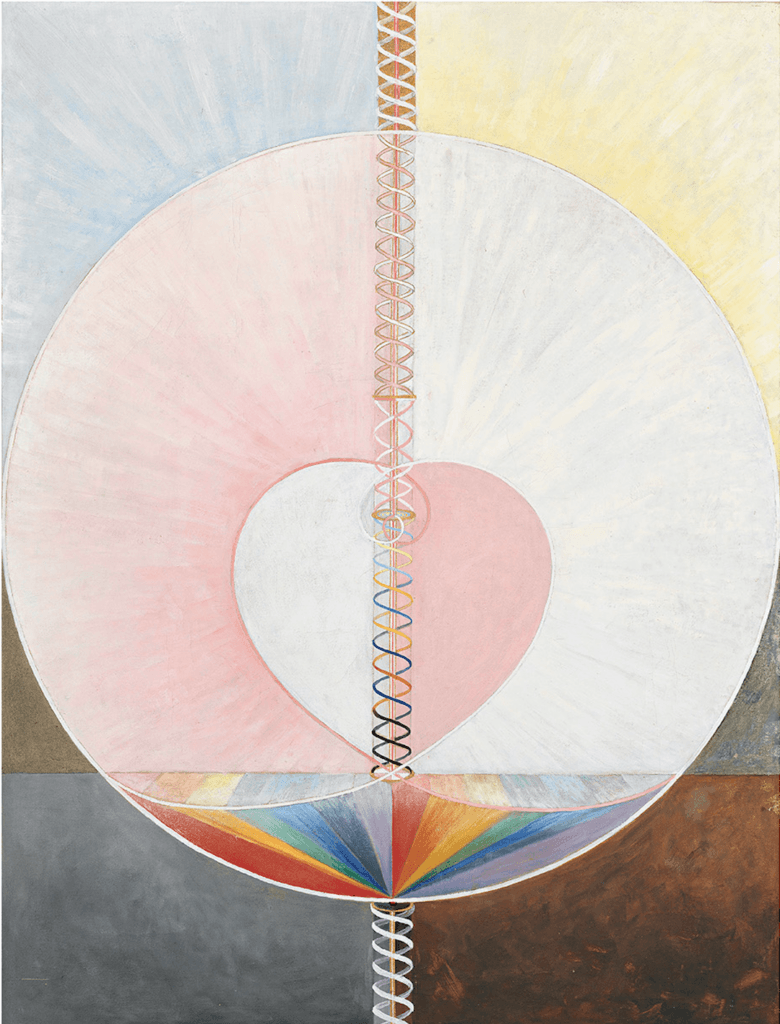

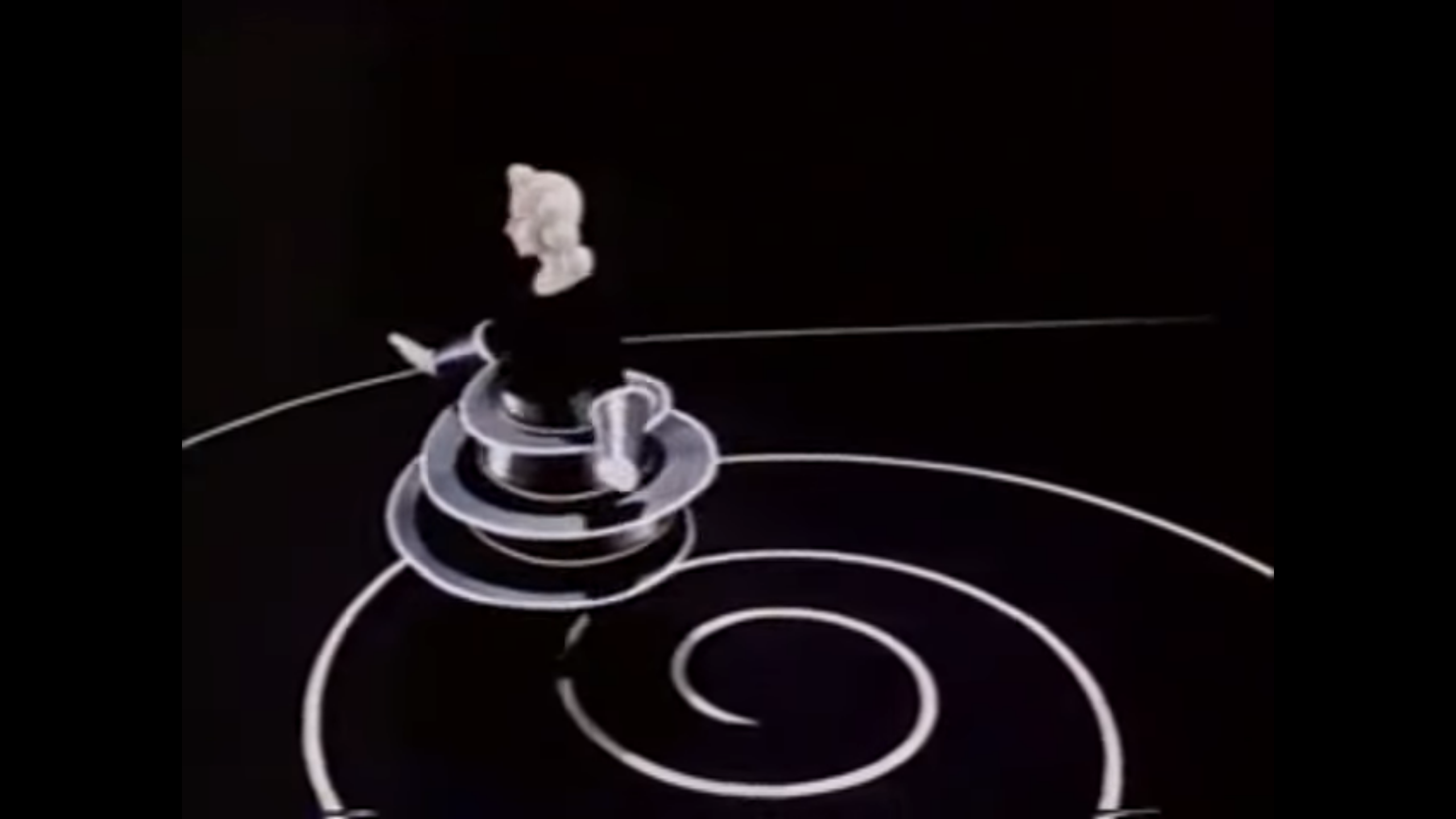

Hilma af Klint, the evanescent goddess of abstract art, was fiercely committed to her self-proclaimed role as a medium. Painting in the early 19th century and influenced by the methods and philosophies of Madame Blavatsky, Annie Besant, and Rudolf Steiner, she studied the otherworldly in codified, colorful, and symbolic apparitions, erratically but with purpose, in her sketchbooks and on canvases. Her work, which predated a canon of abstract artists (Wassily Kandinsky, André Masson), remained unknown until almost a century later: works that brought on swans, snakes, and slivering helixes like strands of DNA or alien script, with fearless bright hues unleashed onto the canvas.

Image: What a Human Being Is, c.1910, Hilma af Klint

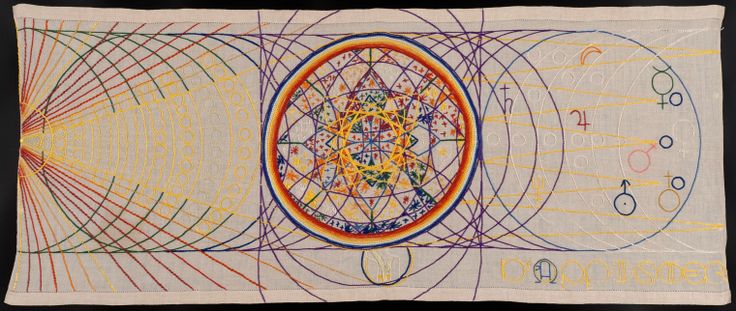

Af Klint’s oeuvre was based on a complex religious philosophy; “images came to her from higher beings residing in a dimension only discernible through clairvoyance,” as BreeAnn Midavaine wrote in “Hilma af Klint: The Medium of Abstraction.” Though Af Klint’s interest in the occult started early, she later became one of the five women in De Fem, a group of likeminded spiritual enthusiasts. Her life spanned the implosive, supernatural period when other kinds of mediums to the unseen world — electron microscopes, X-rays — had renewed theosophy, a methodical study of spiritualism. And as real-world modes or evidence of the unseen materialized, so did, famously, the phenomenon of their diabolical equivalents known as “influencing machines,” looming malevolently in the imagination of paranoid schizophrenic patients. One psychiatric patient in Switzerland, Jeanne Natalie Wintsch, seemed to identify with the newly available broadcast technology in her 1924 stitch work, Je Suis Radio.

Je Suis Radio, 1924, Jeanne Natalie Wintsch.

These technological expositions, for Af Klint, “combined with her examination of the philosophies of Madame Blavatsky, Annie Besant, and Rudolf Steiner, greatly influenced her artistic methodology and style, which varied from geometric abstraction to an early form of Surrealism” — a new movement set to release the subconscious by disregarding many conventions of form. Af Klint’s mystical excursions were central themes to André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto (1924), in which he described surrealism as “pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought.” And in this process, Breton and his fellow surrealists, Salvador Dali among them, would use automatic writing, hypnosis, and other experimental devices meant to to extract the unconscious mind by unveiling its minute physical manifestations.

Yet Af Klint closeted her virtual adventures, and was principally known as a landscape and portrait artist. Her mentor Rudolf Steiner at one point advised that even though her “laboriously discovered signs and symbols” were not understood by many of her contemporaries, it was “the future she was working for.”

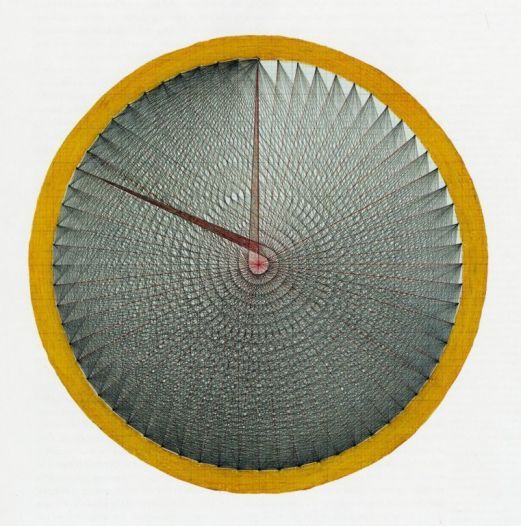

She wasn’t really alone, when you discover the correlations with the work of Emma Kunz. Both women: an unsurprising parallel given a society’s gendered prism of certain “domestic” practices, healing, storytelling, weaving. Kunz, a Swiss weaver-turned-autodidact-artist, would produce complex colored-pencil diagrams in long single sittings to meditate and visualize the invisible, which she used in her independent hypnosis practice through the 1930s. She was born into a family of weavers, too, and so she grew up alongside an ancient profession entwined with a sense of magic and myth, repetition and time, historically used to speculate about the fabric of universe — an early installation of “string theory.” Like Af Klint, Kunz was after “everything,” all of which, she said, “happens in accordance with a specific system of law, which I feel within me, and which never allows me to rest”; the coordinates of the junction of nature, art and life, that somehow serenade everything around us. Ambitious, maybe, but not far from the way we have computerized a collapse of space and time into our lives. Like Af Klint, also, Kunz’s work seemed out of time: “My art is destined for the 21st century,” she said.

Le Grand Jeu, Emma Kunz.

Thus the serpent sheds and the future arrives with many promises for change; when we started hearing each other through the telephone line, our artists were already dreaming of flying cars, cyborgs, and telepathic transportation; screens would eventually question limits of the physical world. And while theorists wrote about culture and knowledge production in the wake of mass reproduction, artists’ relationships with their tools were revolutionized. Testing the boundaries of optical perception, 20th-century technologies extended sensory expressive capabilities of humans into sound, touch, animation, and virtual realities in art and science (fiction), while in life they left insidious marks of their presence, culminating into the way we interact in this century.

On her recent curation of the Whitney Museum’s exhibition Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905–2016 (named for H.P. Lovecraft’s alternate fictional dimension) Chrissie Iles recounts this dizzying but important chronology most prescient. She points to the crucial influence of 1920s Weimar Germany on the onset of technological art: “In contrast to France, where experiments with the cinematic were shaped by a dialogue with Surrealism and literature, in Germany, artists were influenced by the Bauhaus and the new industrialized environment, and their work engaged with abstraction, color, light, the cyborg, and technology’s relationship to the body in the spectacular immersive space of the city.”

With the bloody battlefields of the newly mechanized WWI, artists became sensitive to the amalgamation of technology and organic life — or the flesh, as wounded bodies were “fixed” with prosthetics. The fascination with hybrid compositions can be traced all the way back from Egyptian iconography and Assyrian mythology, to the 20th-century surrealist reincarnations in Max Ernst’s human-bird renditions (his alter-ego, Loplop), to the “mechanical analogs” in Edward Hamilton’s 1928 Comet Doom and Captain Future, or in the more nefariously Frankenstein-esque The Mechanical Man (1921), a half-survived silent film by André Deed about a deadly man-made robot. In Dreamlands, Iles exhibits Oskar Schlemmer’s Das Triadische Ballett (1930), a surreal video of models dressed as cyborgs, which evokes a naive, whimsical sense of future life as a perfect myriad of form and biology. And yet, the film, with its various dancers in outfits redolent of automatic apparatus, miming gestures in repetition, is aphoristic of the emergence of a new aesthetic: one recreated easily by a 3D artist today, in figures with anachronistic movements and textures.

From Oskar Schlemmer’s Das Triadische Ballett, 1930.

Perhaps we can never look at the moving image and be proselytized into its unearthly qualities as artists once were. Anthony McCall’s Line Describing a Cone (1973), for instance, a 30-minute looped 16mm projection of a dot lazily and methodically tracing a circle like a supernatural clock, experiments with not just the somatic quality of the virtual, but its message. The piece requires the audience’s movement and participation as it plays with light and shadow, in a speculative materialization of time. But Iles quotes film critic Jim Hoberman to describe the shifts in our optical and cinematic perceptions — the multitudes of planes where so-called technological aesthetics permeate, where “artifice and reality are becoming versions of each other.” Everything is a simulation, a la Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation. And the real and unreality, in a modern visual sense, have never been married so seamlessly as in CGI.

Like for the militant Tom Cruise in The Edge of Tomorrow, suspended in a 24-hour time loop to “save the day” and repeating his mission from the beginning every time he dies, the interchangeable role of reality and fantasy stands in for a “reset” button we press as we forge ahead. Both the visual lexicon and format of the film are identical to computer games where you “lose” — not always accidentally — and repeat the round. Out of the many films inspired by different game franchises, director Doug Liman succeeded in creating a meta experience so immersive that it’s almost unrecognizable, because the game format is never manifest but readily accepted as the plot. And so, the digital-scape evolves from the influenced to influencer, and the audience participates in its latent surrealism.

The interchangeable role of reality and fantasy stands in for a “reset” button we press as we forge ahead

The spirit and the body; the virtual and the physical; these binaries are becoming less and less relevant between art and articulations of what we are — or are becoming. Outdated technology becomes an explicit part of the message in art as a retrospective event, or an introspective of the medium, like when any filmmaker today uses a Super 8, or how Polaroid is summoned back from obscurity because of an aesthetic anchored in time. As a thing of its time, technology-laced art is bolstered by nostalgia — a feeling that grips you by the neck, tickles your throat with joy and sadness and warmth, and is a tool in itself. But as we medium-hop with greater frequency, every “obsolete” old technique or product, though valorized for its imminent scarcity, is increasingly akin to old skin cast off the same body of work. At another London Frieze booth last year, I stopped to marvel at Sylvie Fleury’s aerobic exercise videos installation. The piece, A Journey to Fitness or How to Lose 30 Pounds In Under Three Weeks was first shown at the Venice Biennale in 1993. Looking at it, frozen, I remembered my best friend and I imitating her mom to one such video in their living room in early ’90s Iran. The videos are enigmatic. What they show (a studio full of synchronized Barbie-esque women exercising sans sweat) seems real: They are real, but no longer exist. Their familiar semantic language is a portal to a shared dream, evoking an emotive response to the seemingly cool machinations of the digital.

A nostalgic reawakening: Much of art production in the digital realm is much less about originality, but about what Claire Bishop called a “meaningful recontextualization of existing artifacts.” Assemblage or collage as a repurposing of old tools is not a novel technique, but has very different concerns in the digital age. “Faced with the infinite resources of the internet, selection has emerged as a key operation: We build new files from existing components, rather than creating from scratch,” Bishop writes. Questions of originality or authorship are less central, publicly, to contemporary creations. Camille Henrot’s video-installation, Gross Fatigue, a vertiginous video montage of a multitude of objects, animals, and abstract compositions, viewed on a computer screen sidelined with folders opening into new folders, is a perfect representation of this. So is Tumblr, bought in its prime by Yahoo the year Gross Fatigue exhibited. Each is a reflection of the serpent’s avarice.

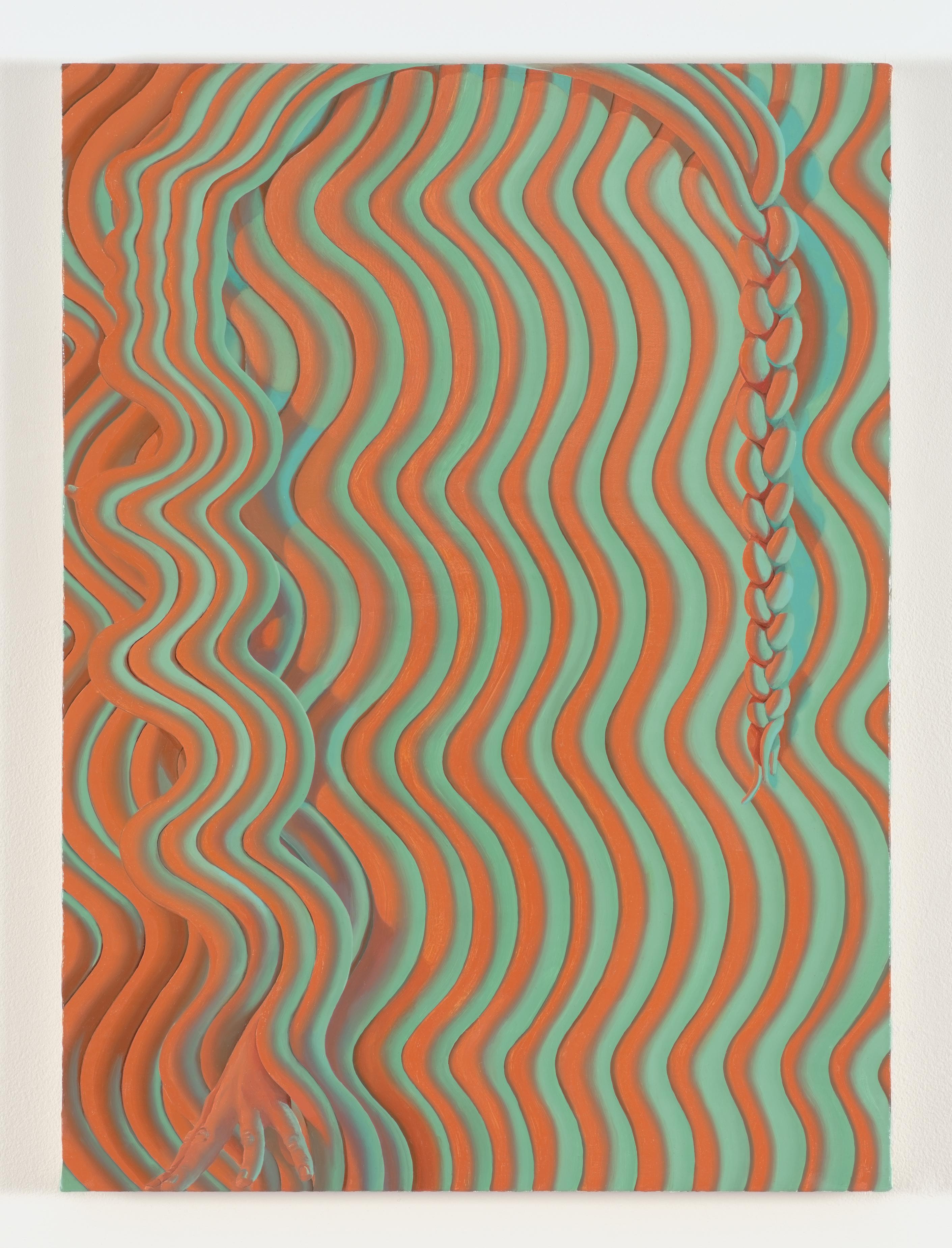

Digital space offers a boundaryless domain, a disembodied dimension with an entirely different government. Af Klint had a self-evoked duty to materialize a spiritual entity, and she devised codes and symbols to formulate her visions. “The artistic gesture,” writes Bracha L. Ettinger in “The Art-and-Healing Oeuvre,” “paradoxically becomes a reaction to what in fact is not yet there, to what is yet to come, to what the artistic gesture itself is about to produce.” Like the snake who would paint by casting off its scales, she writes, some artists’ creative gestures “do not originate in decision or will to produce this or that image, but concludes a psychic trajectory that also participates in regression, yet, contrary to regression, it creates, as by a backward movement, like a reversal of the course of psychological time, a stimulus” — the stimulus of a “gaze” playing behind the picture’s “screen.” But our collective digital experience today has already engrossed us in a virtual vernacular, from emails to Facebook likes to emojis, most being accessible enough to be reproduced and understood or repurposed endlessly, even through, as the coiled green snake famously was, the successive installations of one celebrity feud alone. Ridley Howard paints pixelated abstractions, repurposing the otherwise limitations of representational technology. Camille Henrot prints tens of banal and unanswered company emails in her installation Office of Unreplied Emails (2016), bringing to physical reality the neglected debris of digital communication, effectively dissolving what Claire Bishop refers to as “the disembodiment of the internet,” where “the physical and the social were pitched against the virtual and representational.” The internet, ouroborically, asks us to reconsider the very paradigm of an aesthetic object as that of a one-way flow of information: Can communication between users become the subject of an aesthetic?

Looking at the mainstream contemporary art community’s delay in embracing and recognizing the digital sphere at the time, Bishop mentioned the fear of code, the unknown system that governs our digital discourse. Would Af Klint today be painting the matrix? And are we afraid because we are repulsed by some other ubiquitous presence that, like the giant Spider evoked by Louise Bourgeois — Maman, an “ode” to her mother, also a weaver — hovers over humans. A reminder of our own obsolescence but as protection, too, of our legacy.

We are repulsed by Joe Pascal’s realistically deformed, grotesque creatures moving eerily in few-minute-long videos. Or by Sevdaliza’s visual and sonical, otherworldly That Other Girl (2015). The one-time niche sphere of techies and glitch and net artists, reduced to the monochrome of “new media,” is expanding, slowly seeping into the mainstream. MTV is trying it, and there’s this beloved Method Studio viral motion picture ad. In Eastern mythology, the snake is the symbol of duality, perceived to be both male and female, its poison the source of a fatal venom but also the antidote, the shedding emblematic of regeneration and immortality, yet slithering so close to the underworld as if traveling between the two realms. Mär (snake) in old Persian or Pahlavi language and Sanskrit means death, but mar in the Mazandarani dialect of Persian is rooted in the word mother and female, again, evoking both death and rebirth. In the same language, bimär, the word for a sick person, is composed of bi (without) mär (snake), an homage to the ancient Roman Asclepieia snakes that healed disease; being without it means illness. It goes on and on, this dialectic, emblematic of itself undefined, feeding off itself, transferring one meaning after another, shaping and reshaping, shifting, shedding, moving between worlds and making in its placelessness a world of its own.