NEW FEELINGS is a column devoted to the desires, moods, pathologies, and identifications that rarely had names before digital media. Read the other installments here.

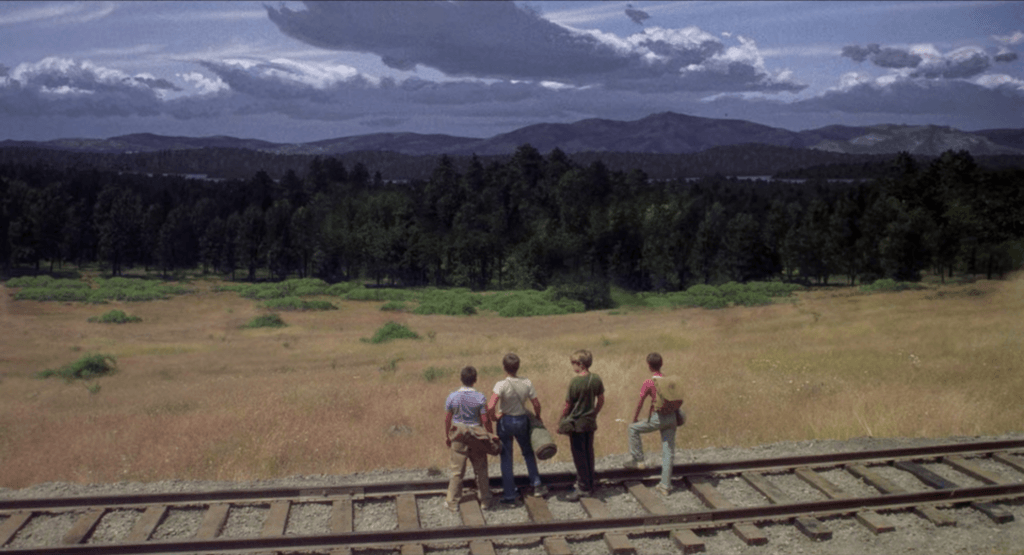

“I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was 12,” types the grown-up protagonist in the final scene of the 1986 movie Stand By Me, “Does anyone?” I first encountered this movie on one of those nostalgic, “I was born in the wrong generation” types of cinema Tumblr accounts in 2012, when I was about that age. When I watched the whole thing, I found it wholesome and wholly unrelatable. The movie chronicles four small-town boys who, yearning for adventure, go looking for another kid’s dead body, rumored to be several miles outside their small town. Their journey on foot frames the dimensions of adolescent friendship, as the movie explores the boys’ dynamics through trials, betrayals, and quiet moments of brotherhood. After the climactic culmination of their adventure, the film ends with a postscript describing how the boys ended up drifting apart and out of each other’s lives as they got older, and finally, a grown man with two children of his own, the main protagonist and narrator wistfully remembers those long-gone summer days of tweendom.

I sensed the film’s finality — the enclosed, off-the-grid adventure preceding a total break in connectivity between friends — wouldn’t ring true in real life

Stand By Me depicted a heartwarming adventure that was thrilling and then, as the plotline goes, was definitively over, until the narrator returns to romanticize his mortgage-free age to the nth degree. I was never a white boy from a small town, and I’ve never seen a dead body, but the movie’s foreignness to my life was of a completely different ilk: The finality of it all was severe in a way I didn’t understand. At 12, it’s hard for anyone to imagine that their bosom buddies might one day become strangers, but even then I sensed that the finality in the film — the enclosed, off-the-grid adventure preceding a total break in connectivity between friends — wouldn’t ring true in real life.

The mediascape I was raised on rejects and undermines this sense of finality, and this delicacy of individual life experience. While much has been made about the overload of nostalgic pop cultural mining in music, fashion, and other media content, the very structure of our most prevalent plot devices indicates a cultural atmosphere of temporal erosion. Fictional plots today may be taking our increased continual connectivity into account, eschewing the tight contours of the singular, removed adventure narrative that once defined youth media.

“Teen movies” in the 1980s were nostalgic for every moment as it happened — every kiss was immediately fodder for a story to tell the grandkids, every adventure was wistfully completed, and every friendship was hallowed. Of course, blockbusters were nowhere near niche, and by and large my milieu has based its perception of “the analog era” of youth culture on John Hughes, with its nostalgic expressions of the delicacy of life, in which friendship and love are valuable because they end. But the lessons didn’t exactly sink in right away: The first time I watched The Breakfast Club, I immediately started thinking of what might have happened next, wanting to believe in some fan-fiction worthy scenario in which they met up at school on Monday morning and proceeded to become a “found family” kind of friend group. Realistically, even with a nugget more perspective and empathy than they had before the events of the film, they went back to their cliques and moved on.

The presence of “hard nostalgia,” or retrospective feelings for a definitively past experience, used frequently in plot devices preceding the consumer internet, is now a subject of nostalgia itself, in retrospectives and bloggy collections that glorify the concept. Much of the appeal of Tumblr itself (in its golden age when I was younger) was how you could curate — and change, at will — your own expression of identity based on what type of accounts you followed, the aesthetics of the posts you reblogged, the visual background theme you chose, the song you could queue to play when someone visited your blog. Each of these things could be instantaneously overhauled, given most users followed others based on their contained, Tumblr-specific digital presence rather than knowing anything about their daily life or what their face looked like. The ease with which you could so quickly and definitively change your Tumblr expression was a means of firmly segmenting the changes in adolescent identity and community in a way that was largely impossible otherwise.

In contrast to “analog era” movies that idealized youth as a bittersweet place of departure, my experience of youth media is one of continuity

In contrast to the “analog era” movies that featured encounters with “hard nostalgia” — idealizing youth as a bittersweet place of departure, as something that is over just as it’s happening — my experience of youth media is one of continuity. Movies and TV shows today account for continuing digital connectivity in their use of equally weighted character perspectives, stop and starts of individual storylines, and a default industry-wide push (granted the viewership numbers) toward a stream of sequels and reboots. In popular entertainments marketed to me, stories are supposed to go on forever — bolstered by endless spin-offs and fan extensions. Some of my favorite franchises like the Avengers and Star Wars have spent recent years trading on their own history, with callback upon callback creating a feedback loop out of their legacies. An entire cottage industry has emerged out of finding nostalgic and referential easter eggs in these kinds of films, reifying the iconic nature of what came before as it is continuously brought into the present. They survive on the commodification of their own history — and so do we, in a social sphere that mirrors the entertainment sphere: in ongoing curation, narrativization, and calculations of value in an algorithmic setting.

I got my first iPhone and Instagram account when I was 12 years old, and to this day I still follow elementary school classmates, several intense, short-term friends from summer camp, and a plethora of other ex-friends and acquaintances. These are the kinds of relationships — fleeting but indicative of significant eras in life — whose memories older generations may have kept neatly enclosed in picture albums as they, quite separately, moved on to different stages of life.

My mom’s photo albums often have a thematic element: “when I was working in New York,” “winter of 2002,” “the friends I had in my late 30s.” There is a natural division between these different stages, each photo consciously grouped with its temporal peers. When she wonders where an old friend ended up, armed with only their name and a decades-old landline number, the 10-minute search is delegated to me. I couldn’t imagine passing so much time without any sense of what a former friend was up to, even without any direct communication with them, their major life events remaining unbroadcasted and unknown. Not having that full file of information, even in relation to someone I never expect to see again, is disorienting. To my mom, new chapters, new stages, and the new relationships that come with them, is life.

In contrast, my memory albums are endless and ever-coagulating, flowing together to make one undefined body of memories in my Photos app. And beyond that, these “memories” are supplanted by new updates — updates that are outside our shared sphere, so far removed from the version of them that I once knew — in an ever growing “book” of tenuous relationships on social media. Rather than with a bang, everything seems to end with a series of whimpers: your ex-whatevers may stop liking your posts or “soft-block” you if your relationships get really dire. But even then, data networks in the form of social media ask us to retain as much of our ephemeral web of frayed relationships as possible, in the hopes of one day being able to turn them into social, cultural, or even economic utility. I am fed connection, or at least “staying in touch,” on platforms that persuade me that the arduous upkeep of these loose ends is the key to success and happiness. But hanging on to bygone relationships has begun to feel like a substitute for personal growth.

Films today survive on the commodification of their own history — and so do we

What defines new relational stages today, given they’re always mixed together with old ones on platforms eager to keep you engaged? How do you mark a new “era” when you’re keeping tabs on the day-to-day lives of hundreds of people who will never tangibly occupy your day-to-day life again? Maybe I’m just a sucker who doesn’t know how to click the unfollow button, but the fact that I’d hardly considered it before now is the result of a certain tentativeness that has been ingrained in my relationships and experiences since I first accessed social media — a refusal to be the one to close the door on the past, and the fear of missing out on the possibilities that may still lie behind it.

When I skim over the memory of somebody that I used to know, their profile is ever-expanding as we move along our parallel paths in life, with Instagrammed, Snapchatted, and Facebooked updates like their college choice or their sorority pledge, and even updates of absence: that boyfriend who suddenly disappeared from their posts. A crystallized memory of a childhood friend is always flickering with a version of them who I no longer know. Rather than continuing to get updates, I could delete the connection altogether. But that definitive unfollow feels like an unnecessarily big step, bringing down the hammer and forsaking the good times that make me continue to cherish our tenuous line of digital connection. It means shedding who I was and disposing of who I knew them to be when we were last connected.

This coercion to extend every adventure as long as possible — the nostalgia continuum — is the connective tissue fastening past experiences to the logic of the “feed,” which cuts the flow of experience down into atomized parts that are readable to tech platforms, enshrines chapters in life to make them rankable, interactable, and presentable to you over and over again, usually in a nostalgic form. Platforms often act as though they are the narrator of your life, like the writer in Stand By Me. Experience is organized for the user, who is supposed to live the past as the present. Beyond social media, this new form is fortified by popular culture in a never-ending string of sequels and reboots, memories that bleed through their temporal endings. But under the rule of the nostalgia continuum in hyper-connective social media culture, none of these memories live in a silo, and are instead constantly revisited and revised.

The nostalgia continuum consistently threatens my ability to move on and out of a blue-light tinted past, and it makes definitively turning the page on any “chapter” in life nearly impossible. In absorbing the lessons from ’80s cinema, I understand that you can’t really appreciate an era in your youth except from a temporal, and ideally a physical distance, and the pressure to do so persists over a digitized social sphere, where this sense of distance is eradicated and memories are never given a chance to breathe into the past.

From my born-in-2000 pop cultural vantage point, life may move pretty fast, but there isn’t really a chance, as Ferris Bueller theorized, that “I’ll miss it if I don’t look around.” The “feedification” of social life implies infinitude — feed, after all, is not only a noun but an active verb. It’s the ability to mediate your life into consumable packages (with the helping hand of platforms built to encourage you to do so) to be used for social or economic capital. We’ve moved past looking at the past with “rose-colored glasses” and towards examining it with a wide lens, contextualizing every post within the poster’s personal brand. The brand is ever-evolving, and so are the memories, in service of it.

College, I’m now learning, is a pressure cooker with a fixed end date, but from day one you’re told that every move you make will ripple across your entire future. Every social move you make will ripple across your plethora of profiles, too. The old adage “if you want to know someone, look at the friends they keep” has never been more apt nor more strategic, encouraged by features like the Snap Map which aim to show who was where, when, and with whom as further means to construct one’s own outward facing profile.

One of my greatest fears is living my whole life commodifying my experiences and relationships into neat, consumable packages with the promise of positive returns. I hope to look back on the things I’ve done with rose-colored glasses rather than with the sheen of a calculable path to algorithmic happiness. I hope to have some nostalgia left to look back with, rather than having extended each adventure past its run time.