The idea of “gamification,” like other technological innovations, has started to become invisible. Coined in 2002 by programmer Nick Pelling to describe consumer electronics interfaces, gamification entered broad usage after its 2008 adaptation to software, where it meant applying game dynamics to web enterprises to increase engagement. A decade later, the word, like “Web 2.0″ or “teleconferencing,” already feels like outdated jargon not because it’s obsolete but because gamification is everywhere and finally ordinary. According to Google Trends, usage of “gamification” peaked in 2014, at least in the United States. But the term’s declining use is more an indication of how ubiquitous it is — life is so thoroughly mediated by apps that the condition doesn’t seem to require a special word. It is just life as we live it.

Initially, “gamification” helped individuals make sense of the perceptual revolution sparked by the widespread adoption of smartphones. Though the logic of gamifying behavior is not new, the sensors and connectivity of phones allowed tech companies to bring gamification’s necessary prerequisite — behavioral tracking — into many new domains. Countless apps exhibit gamelike principles that have become as normal and familiar to their users as crossing the street. The phone, as a handheld sensor, not only records the world around it but inscribes its apps’ logic onto the world, orienting users’ behavior toward newly legible metrics and rewards — not merely content-level metrics such as likes and retweets but also badges, follower counts, verified checkmarks and other indicators of personal status improvement. Hence Foursquare could gamify going places by prompting regulars at bars and restaurants to quantify their loyalty and vie for “mayor” status, while Instagram gamified photography, turning it into a performative act with public-facing stats. The idea of caring how many likes a tweet or Instagram post gets may seem absurd until you start to use them. Then it seems absurd to behave as if you don’t care about those results. Internet users have learned to value these apps’ once-frivolous symbols that now, in many cases, amount to professional credentials, potentially as important as a grade point average or SAT score.

Games are a way of seeing the world, despite whatever distortions of reality they urge us to accept

As game mechanics have become more naturalized and more commonplace in more facets of daily experience, games themselves have converged upon a similar mixture. The recent evolution of video games, particularly the massively popular Fortnite, suggests a seamless merging of game and nongame activities. In practice, Fortnite is less an outright game than a gamified environment where last-person-standing competition coexists with activities that don’t serve the players’ overarching game objectives — such as DJ sets and ambient socializing. That juxtaposition, in turn, is not so different from everyday life, also a gamified environment characterized by intense and often unacknowledged interpersonal competition.

But games like Fortnite also suggest a line of flight from gamification’s narrow fixation on explicit goals. In an environment that presents its players with an urgent, all-or-nothing imperative, as most video games do, Fortnite shows us the possibility of opting out, however temporarily, even if we don’t reject the premise of the game itself. Game dynamics need not dictate every aspect of behavior, even within an actual game. As life is increasingly pervaded by such dynamics, this lesson is more useful than the belief that we can simply escape to a reality free of games. The gamification of digital existence, by this reasoning, was a key precursor to the popularity of Fortnite.

An old, variously attributed piece of corporate wisdom advises that an organization can’t manage what it can’t measure. This turned out to be a prophecy for digitally saturated life, as our devices have become a means for making more of our experience quantifiable. This, in turn, changes the way we view that experience. Formerly unquantified practices, once recontextualized as app-assisted activities, enter a framework of metrics, KPIs, and measurable goals, which we tackle with a business-like enthusiasm for progress and improvement.

While fitness, for example, has always been a sort of game, its scope was previously confined, spatially and temporally, to the workout itself, along with the few outcomes we could actually measure, like running pace or maximum weight lifted. But iPhones quietly count the total daily steps we take by default, opting us into a daily competition against ourselves that we didn’t necessarily sign up for. Measuring steps expands the gym’s logic of self-competition to all of waking life, making everything an exercise opportunity. If we once recognized this as “gamification,” we’re more likely now to view it as just another part of daily routine. For that matter, we might find ourselves playing these fitness games to serve the priorities of other parties, like health insurance providers.

Wherever there is quantification, there is gamification. This has long been the case, but so much more is now being quantified. We learn each January how many miles we ran last year, how many minutes we spent meditating, and which songs we listened to most frequently. In all likelihood, we didn’t specifically ask to know most of those statistics, but once we do, the activities they measure feel illegible if not impossible without them. Our behavior is thereby continuously nudged to adapt itself to the device’s affordances. That feeling, of course, increases our dependence on those apps — it “engages” us — and thus supports the apps’ underlying business models.

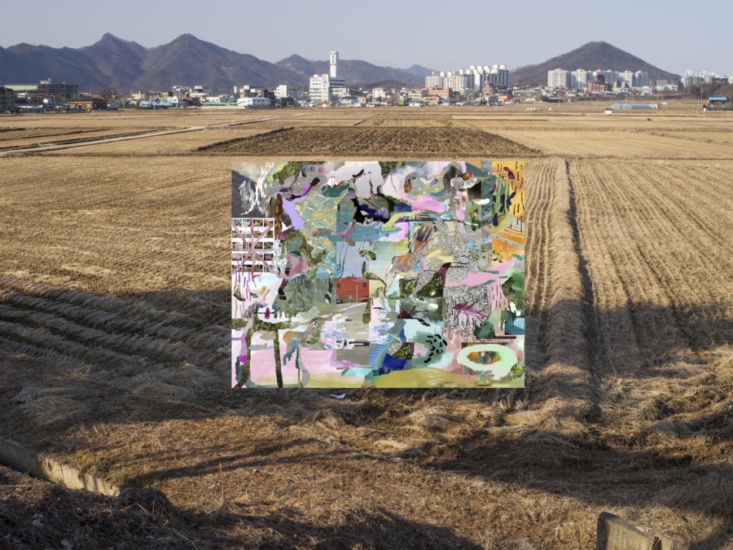

Games are a vector for the rationalization and monetization of new spaces, the perfect neoliberal mechanism, even when (or especially when) they make those spaces more “fun.” Games capture our attention and draw us in, asking us to accept their rules and adopt their priorities. They are a way of seeing the world, despite whatever distortions of reality they urge us to accept. What is gamified becomes more visible and more palpable, even as the gamification dynamic itself vanishes into familiarity.

Gamification as a label may be receding from consciousness, but games are obviously still everywhere. The video game industry earns well beyond $100 billion in global revenue annually, and this doesn’t include activities that are merely “gamelike” or gamified. Augmented reality games like Pokémon Go and Ingress merely bring gamification logic to a conclusion: Is the now-ordinary quest to accumulate 10,000 steps in a day by any means necessary so different from the circuitous journeys made in pursuit of digitally rendered creatures? The distinction between game and nongame environments blurs. In both cases, behavior is encouraged that appears irrational to anyone outside the context of the app providing guidance. Both environments appear equally amenable to being modeled by software and administered through a codified set of formal rules.

Marc Andreessen famously observed that “software is eating the world,” but that statement has as its corollary that games, too, are eating the world. Software’s ability to model, measure, and otherwise represent reality allows it to layer game mechanics atop behavioral data. The potential for digital abstraction and simulation are nearly unlimited, and so is the potential scope of game dynamics. But representation in software necessarily simplifies reality by eliminating certain details to better emphasize others: Facebook reduces the messy variability of relationships to a standardized social graph with equally weighted connections, while Yelp and Foursquare depict the urban landscape as nothing more than a constellation of bars, restaurants, and retail stores. These simplifications amount to an expedient map-territory distinction, removing information to emphasize what remains and make it easier to navigate and interact with, if mostly on the app’s terms.

If Fortnite is a skate park, then Call of Duty evokes the mall-like spaces where tight control and total design are mapped back onto the physical world

If we’re constantly engaging with reality through the kinds of simplified models that apps and games represent, we might wonder where the more “real” reality that supposedly lies behind this software is found, if anywhere. But as Venkatesh Rao argues in his essay “On the Design of Escaped Realities,” the history of civilization consists not of a falling away from reality but of a long succession of attempts at escapism, which he defines as “a deliberate entrance into a simpler reality, as opposed to an unplanned entrance into a messier one.” There is not some ultimate, pure reality that we might eventually access after peeling away all the simplifying layers — such a reality, in his view, exists more as a theoretical ideal than something possible to experience in everyday life. Rather, he points out that there is a deep history of escapism through a variety of changing means that are determined by technological possibilities as well as cultural conditions.

Environments characterized by game dynamics are no more artificial than their nongame counterparts. Instead, games are yet another interface for reality. The practice of playing games is an escaped reality just like school, the workplace, or any of the other environments in which we spend most of our time: That is, the space of games distorts and simplifies a broader enveloping reality to make certain practical purposes seem more achievable. Institutions, ideologies, and games are all escaped realities in the sense that they, like software, simplify a universe that is too complex and overwhelming to apprehend directly. The formalized rules and rituals that characterize all these environments help streamline and orient experience at the expense of a broader, more complex reality. Virtual reality and augmented reality are merely the latest examples of such simplified realities, drawing upon the most recent technological developments. But the simplifications that gamification requires are not native to the digital realm; they are everywhere. And as Rao’s essay suggests, logging off from them will not re-immerse us in genuine reality.

The difference, then, between game and nongame spaces may be slighter than we’re tempted to imagine. What distinguishes the two is not their relative fidelity or authenticity, but the directions of escape they offer, or the lines of flight they facilitate. Michel Foucault, in a 1967 lecture and subsequent essay, posited as heterotopias those “real places … which are something like counter-sites” that create “a space of illusion that exposes every real space, all the sites inside of which human life is partitioned, as still more illusory.” He lists gardens, cemeteries, fairs, and prisons as examples of heterotopias. The spaces shaped by gamification may also serve this purpose: Instead of merely offering an escape from reality, these spaces are counter-sites that can remind us of the nested artifice that pervades and constitutes civilization — outside of which we can’t perceive reality at all.

Rather than escapist fantasies, we can understand games as spaces to relearn a kind of being that has receded from many other environments

In this sense, games are environments that make it easier to see the world in general as a kind of simulation. If subtle, manipulative gamification conceals its presence as a neoliberal apparatus, other types of gamification can shed light on the very same mechanisms, exposing their operation more broadly across different sorts of spaces.

This potential for illumination may help explain what has driven Fortnite’s unprecedented popularity. Keith Stuart compares Fortnite to a skate park, full of “‘dead time’ to mess around and chat.” He contrasts it to the “highly directed experience” of the Call of Duty games, where “every map is dense and claustrophobic and usually designed with three parallel channels that funnel players toward each other.” If Fortnite is a skate park, then Call of Duty, in its contrast, evokes the airport- and mall-like spaces that characterize so much contemporary urbanism, where the tight control and total design that software facilitates are mapped back onto the physical world.

It may just be that Fortnite, unlike Call of Duty, achieves a more seamless unification of game and nongame environments. Though there is nothing exactly new about it as a game — multiplayer gaming has existed for decades, after all, and Second Life and Minecraft had already refined the noncompetitive aspects of such gameplay — what is new about Fortnite is how it foregrounds the intersection of game and nongame space rather than disavowing it. That acknowledgment opens the game’s potential as a counter-site. Fortnite refines the non-competitive qualities of its predecessors inside the context of a battle royale. It rejoices in how gamification has eroded the boundary between game and nongame space to the point that it’s impossible to say where one ends and another begins.

Fortnite, by displaying the easy coexistence of games and nongames, could be seen as a kind of utopia in which players can inhabit both contexts as fluidly as in other domains, with the terms of each made more transparent. If apps allowed the physical world to be more intensely gamified, the inherently gamelike digital universe has the equivalent need to be de-gamified. Previous examples of this shift, like Second Life, didn’t occur within the context of an unavoidable, overarching competition, like Fortnite does. The lesson of Fortnite is that, on an island where every player is trying to hunt one another down, it makes sense to stop and dance for a while. Maybe learning to thrive amid such unresolvable tension is key to surviving the harsh, competitive conditions of neoliberalism — and for this reason, the game could be seen as a mixed blessing, making tolerable an arrangement that would be better upended altogether.

Many people who have spent too much time hanging out on gamified Twitter, posting 140-character missives in the quest for likes, retweets, and followers, might find the Fortnite dynamic inscrutable, but the game represents the full embrace of that experience. We come to social media to hang out and find ourselves gradually playing a game, often to our dismay, and without a clear grasp of the rules. But Fortnite inverts that: It attracts us with the intention to compete and then actually encourages players to hang out and socialize. For all the attempted behavioral engineering to which our devices and apps subject us, we should welcome this development.

Rather than escapist fantasies, then, we can understand games as spaces to relearn a kind of being that has receded from many other environments. Games can remind us or teach us how to carve out oases of calm in the midst of a cutthroat, omnipresent battle royale. As one more of many simplified environments with its own rules and constraints, Fortnite isn’t necessarily more free than the others. But its particular contours offer a different kind of freedom than other spaces where we spend our time. Instead of luring us toward a mirage of more authentic experience, games might teach us how to better inhabit the spaces where we must inevitably live.