Visual representations of the internet most often manifest as intricate webs, like a neural network where even the most tenuous connection is noted, or else a map of independent orbs floating in an infinite sea, their radius determined by traffic. One seeks to reinforce the curious notion that the internet, because of its physical truth as a vast network of cables that connect one machine to the rest, can do the same for humanity. The other situates most of us as an audience to the behemoths of Google, Facebook, and YouTube. Neither seems particularly accurate to anyone who’s ever posted anything anywhere; we are more than spectators, and yet when you set out to showcase yourself — to say something only you can say — you find out almost immediately that nobody is listening. It does not feel like going to a party, or even like chatting with a seatmate in an amphitheater. It feels like peering over the edge of a cliff, into an empty gulf.

But then, that’s how all of cyberspace felt in the age of Blogspot, the transition from the internet as a loose collection of exclusive html sites in the 1990s to something a significant fraction of humanity carried in its pocket after 2007. For a couple years, blogs were the main method for a person who didn’t know a lick of code to establish herself online. The interfaces have changed since, but the idea remains the same. Rather than relying on masses of users and followers to function, like the social networks we’re used to now do, they existed alone. And they have endured.

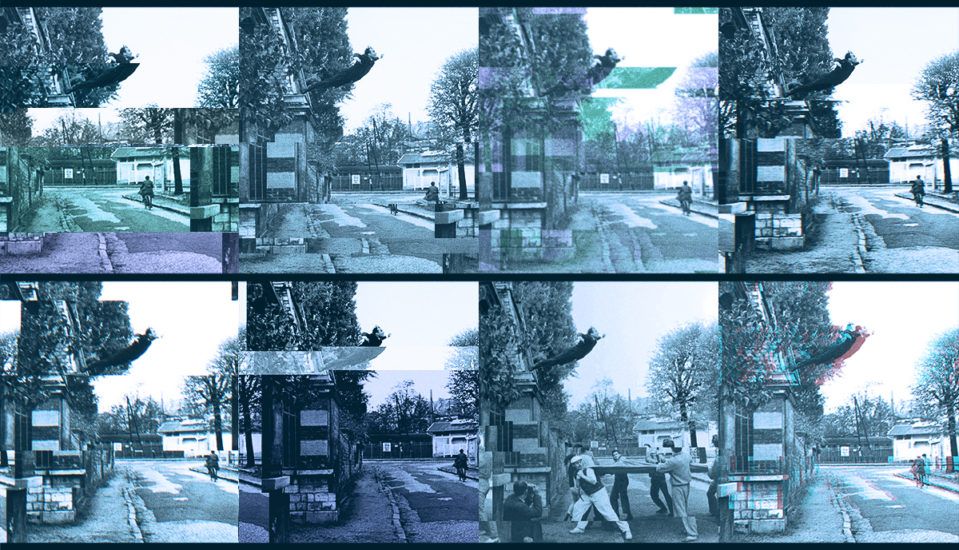

Blogs of olde are severed from the fiber optic network, seeking not to influence or comment so much as to simply capture a fleeting moment in the author’s life

On one blog called “Beyond Mundane,” a self-described “Black American Southerner with a particular point of view” has chronicled his thoughts about technology and identity since 2005. In early February, he wrote a post titled “Executive summary of my situation.” “Discovered some important and powerful things including important ideas,” he begins, “However, ran into a silent treatment from established experts.” Click “Next Blog” in the toolbar and find a woman “in the backwoods of NH” who writes that “I’m pretty sure I have no space left in my brain to access any more creative thoughts than what goes into this.” Next blog: a Kenyan immigrant in Maryland who writes against a vivid, pink background about being betrayed by a sweetheart. “I am the same caring, loving person I have always been,” she writes, but “you are still a selfish psychopath.” Click again and find “a flibbertigibbet who lives in Central Iowa” and who “likes papercrafting, photography, traveling, music, the beach, reading, going to Jimmy Buffett concerts, soccer, the Iowa Hawkeyes, the WORLD SERIES CHAMPIONS CHICAGO CUBS, the New Orleans Saints, and tequila & rum.” Click again.

In these particular blogs, present manifestations of a now antiquated form, there is no overbearing Trump presence. No Brexit, no global refugee crisis, no opioid epidemic. The incensed and concerned seem to have mostly migrated to the social internet where the audiences for their opining are readymade. But blogs of olde are telling of a deeper seclusion from the 24-hour news cycle that the internet also allows. They are severed from the fiber optic network, seeking not to influence or comment so much as to simply capture a fleeting moment in the author’s life. “We have in fact only two certainties in this world,” writes Georges Bataille in Inner Experience, “that we are not everything and that we will die. To be conscious of not being everything, as one is of being mortal, is nothing. But if we are without a narcotic, an unbreathable void reveals itself.” The buzz of a notification in your pocket is seductive, but its extended absence can provoke alarm. To live on social media is to forever risk the void. The blogger side-steps that balancing act — instead of fleeting interactions, she fills the void with the work of writing, and does it for no one’s sake but her own.

Such hermitage is easily dismissed as self-indulgent. The conversations that shape culture and public policy, on Twitter and Facebook, are all Very Important. But importance is relative. The Times’ Maggie Haberman, to a “deplorable” Tomi Lahren superfan, is a left-wing provocateur. Put another way: All news is fake, now. The Muslim ban is an abomination, but any coverage that labels it as such, to a bigot, serves only to certify the coherence of a worldview. As long as a story gets likes or generates follows, its objective truth comes second to its ability to codify whatever the reader expects to be reading. The void is filled not with self, but with a sense of vindication.

It seemed easier to delude ourselves that our society had risen above such pettiness before Trump won, to believe that the internet’s cacophony had tamed the void and made it navigable for “everyone” with access. Didn’t all those little floating spheres contain the same trending stories on Facebook? The same recommended videos on YouTube? The cool users, the savvy ones, the ones who can vet an article’s accuracy based on the quantity of white space in its layout, are just waking up to the fact that the whole time they’ve been standing on the edge of a cliff. They are powerless to stop the man leading us into a Know-Nothing abyss. All the links in the world, all that shared knowledge, are still weighted for those who are listening; to those who aren’t, we are snowflakes, and we will melt.

In 1909, Italian theorist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti called for the glorification of war, “the only hygiene of the world”; he wrote of exalting “the aggressive gesture, the feverish insomnia, the athletic step, the perilous leap.” His conception of Futurism was an embrace of the rapid modernization of Europe — he extolled “the factories hung from the clouds by the ribbons of their smoke,” “the adventurous steamers that sniff into the horizon,” and “the broad-chested locomotives, prancing on the rails like great steel horses curbed by long pipes.” To him, these marvels of engineering were what would deliver Italy (and by extension the world) “from its gangrene of professors, of archeologists, of guides, and of antiquarians.” Which is another way of saying: from facts.

When World War I broke out, Marinetti agitated for Italy to join the fighting; after peace was negotiated, he co-authored “The Fascist Manifesto,” the founding declaration for Mussolini’s League of Combat. Marinetti understood that he lived in a time of pivotal change, but while many dreaded the conflagration that seemed inevitable, he welcomed it. Self-reflection and rumination — those qualities that one can still bump into while scrolling through random Blogspot accounts — were relics of an outmoded past that could and must be erased by violence. At the same time, Marinetti was formulating Futurism, he wrote in “The Joy of Mechanical Force”:“Let us abandon Wisdom like a hideous vein-stone and enter like pride-spiced fruit into the vast maw of the wind! Let us give ourselves to the Unknown, not for despair, but simply to enrich the unplumbable wells of absurdity!” For the Futurists and the Fascists that followed them, absurdity was not charming or fun — it was a manifestation of the frivolity of any action not meant to achieve power.

As long as a story gets likes or generates follows, its objective truth comes second to its ability to codify whatever the reader expects to be reading. The void is filled not with self, but with a sense of vindication

The times have again been overtaken by absurdity, and so it’s as difficult now to avoid feeling apocalyptic as it must have been in the early decades of the 20th century. It’s little comfort that our geopolitics are different, just as the technologies that lend us the feeling of life at unbelievable speed are. We convince ourselves that prologue is not prophecy. We cope.

We hit Next Blog and find a man who claims “mathew 10:39 pretty much explains me” journaling his Crossfit training. Next Blog: daily inspirational quotes and extensive annotations on the LA Times’ crossword puzzle. Next Blog: A Filipino “man in his mid-20s trying to carve a niche for himself in the world.” “A glimpse into the life of a single mom and her (mostly) humorous and (sometimes) painful attempt at finding the man of her dreams.” “A nutrition enthusiast who loves to spend time in the kitchen.” Keep sinking. The void goes on forever.

To abjure an audience is to invite it. For many years, scholars assumed that this sort of self-conscious withdrawal was behind the swiss modernist Robert Walser’s decision, starting in 1924, to compose in a coded language no more than a millimeter or two high — this narrative was certainly served by his subsequent interment at the Waldau Sanatorium. A perception of such an elaborate attempt at mystification is perhaps the most enticing invitation to a reader of all — as David Foster Wallace explained 20 years ago to Charlie Rose, who described Infinite Jest as “complicated and long, compared even to the internet”: “Yeah, it’s complicated and it’s hard and it’s weird but it’s also seductive enough to make you want to do the work to go through that.” For an author to go to so much trouble is a virtual guarantee that what he’s at is worthwhile.

Rather than formulate an experiment that sought to challenge his audience, though, Walser’s perplexing code was simply a means to get his ideas down on the page at a time when he was struggling. “With the aid of my pencil,” he wrote to one editor, “I was better able to play, to write; it seemed this revived my writerly enthusiasm.”

The compulsion to blog, despite the overwhelming indifference of the internet writ large, is not new. What is unique to it, what distinguishes it from scribbling in a notebook you can secure with a key, is that an audience does exist — if only theoretically. Wallace and Walser both had a following that they respectively enticed and avoided. These blogs do not, but their potential readership is infinite. And it’s that phantom presence, out there somewhere in the void, that shapes the work into something distinct from entries in a diary. That’s why when a trawler in the void happens onto these strangers’ musings, he lingers for a while, entranced. The posts did not invite him, but they are still there, and they can still be read. It’s in those moments, more than during any Periscope stream or exchange of Snapchats, that the promise of the internet seems closest: watching and admiring another person’s brain, functioning privately.

We have known the vastness of the universe for some time, but even so we have done our helpless best to extend ourselves into it. We have left footprints on the moon and ordered robots to collect dirt on Mars. We have sent a golden record hurtling through space. The vessel carrying it is going over 35,000 miles per hour and won’t leave the solar system for 40,000 years. We have identified seven planets that may host life — our own, even — and are heartened that they are a mere 235 trillion miles away. We will continues monitoring the void like this until the oceans rise and swallow us for good.

To abjure an audience is to invite it. We write because it forces us to face ourselves, to confront what does exist and value or demean it on its own terms

From a vantage of a million miles, our squabbles, catapulted around the globe on those pulses of light, are fleeting. From that perspective everything is. The void is everywhere, but we must not mistake the stuff we ourselves are made of for the gulf we’re swimming in for — nor drown in it. Sitting down in front of a CMS is like peering over a cliff, but there is more to tossing an essay over the side than a hopeless attempt to fill the unfillable. We write because it forces us to face ourselves, to confront what does exist and value or demean it on its own terms. Like Walser, we take our pencils and write inscrutably because communication comes second to articulating for ourselves the lives we lead. And that process doesn’t always amount to much. The blog is there when you need it, and forgotten when you don’t. We check Twitter every morning, during lunch, on the toilet. A blog is ignored for months, and then returned to, like an old friend. It allows a brief reprieve from the hurtling speed that Marinetti believed would reform the world, if only for a little while.

So click next and find “Various thoughts. Random observations. Mostly my life.” Since 2007, BJ (who works “at a freight company moving freight”) has used her Blogspot to occasionally write about exactly that, and lived up to the stated disclaimer — “Not as boring as it sounds.” In that time she’s defined herself as a “primal, jagged, fierce lioness” and chronicled her struggle to cope with her spouse coming out as transgender and their subsequent divorce. “I thought for a long time I could love the person inside,” BJ wrote in September of 2014, “because this person inside was blossoming into the person they were supposed to be.”

“I’ve been feeling really creative lately,” she wrote a little over a year later, with only a post or two in between, “Not just this blog but also working on a fiction piece. I’ve also been thinking about knitting, which is the first step in actually making something for me.” She hasn’t written since, but the blog remains.

The internet is a void to pour these thoughts into, without any expectation that they will be noticed or commented upon. It is a record — lasting, but ephemeral — that can be left bobbing on the sea, bumped into and noted by the Blogspot trawlers, and then swiftly forgotten with the rest as our attentions wander. And our indifference does not nullify their existence. They have a weight that the constant conversations happening in other, more fashionable quarters of the internet don’t: They are borne not of the attempt to share information — breaking, just in, updated — that will pass almost immediately into history, but rather of an earnest attempt to do just that: exist. They ask nothing of us, no like, no cartoon heart, no signal boost. They simply exist as lodestars in our noisy void, intimate resting places for our screen-soured eyes. It cannot be said enough: they exist. They do what we all hope to continue doing, and they are reminders that that goal should not be taken lightly.