Earlier this year, Los Angeles won the bid to host the 2028 Summer Olympics. Originally the bid was for 2024, but after losing that bid to Paris, the city pushed forward as if 2028 were always the plan. On Twitter, @LA2024 disappeared and @LA2028 sprung up in its place. The website la24.org began automatically redirecting to la28.org. On the path to an Olympics future there are to be no false starts, no bumps or hiccups.

Los Angeles’s bid claimed that “nothing brings the world — or a nation — together like the Olympic and Paralympic Games,” a message of global unity that stems from the modern Games’ origins in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian war. Bound up with this image of peace is the promise of prosperity and a bright future, evoked by new aerodynamic arenas, the efficiency of the televised spectacle, and the procession of athletic accomplishments and records broken.

Expensive and attractive new structures come with the promise of long-term democratic and civic improvement. Host cities claim that the self-contained economy that the Olympics create will have a legacy effect — a future for which its worth overlooking present inconvenience or injustice. Before Atlanta hosted the Olympics in 1996, the Corporation for Olympic Development in Atlanta “pledged to improve fifteen impoverished districts and use the Games to tackle wider problems of poverty and inner city decay,” according to a 2007 study commissioned by the London Assembly. But instead, development ended up focusing on revitalizing commercial areas, leaving “a legacy of ill will amongst particular neighborhoods” that were displaced as commercial developments grew. The same study describes how Athens, which built expensive new stadiums for the 2004 Olympics, sought to create long-term employment and help Greece integrate into the European Union. While employment did rise in the run-up to the Games, primarily in hotels, restaurants, and construction, Greece lost 70,000 jobs in the three months afterward.

For the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, China faced down criticism of its human-rights and environmental record with an all-out aesthetic push, commissioning artist Ai Weiwei and other architects to design the reported $500 million Bird’s Nest stadium, for instance, while authorities jailed human rights activists, journalists, and lawyers and cracked down on a Tibetan uprising. And in 2016, Brazil, despite being in the midst of a national corruption and bribery scandal and major economic recession, hosted the Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, pouring funds into the construction of athletes’ quarters and Olympic arenas. One of these was intended to become a set of public schools, but as of August those plans have been scrapped, and the arena sits vacant.

With each wastefully built and eventually abandoned stadium and each exposure of unmet humanitarian promises, it becomes more obvious how destructive the Games can be for host cities. Given the Olympics’ dark history, it’s natural the Los Angeles 2028 bid asked its audience to “follow the sun.” But what justifies any optimism? The city could point to its earlier history with hosting the Games: There won’t be new abandoned buildings because Los Angeles has pre-existing structures. And the 1984 Games, which generated a $225 million surplus, seems to refute the idea that it will take years of taxes to pay for the 2028 Games. Why can’t the city do it again?

With the focus away from what the Games could destroy, the civic discussion centers instead on what the Olympics are to bring Los Angeles: improved public transportation, including a subway extension through Beverly Hills and another to LAX, as well as a unifying connector line downtown. None of these projects exist solely because of the Olympics, but their urgency and importance has taken on a new tone in light of the impending international event. Ashley Hand, a former strategist with the Los Angeles Department of Transportation, told Wired that the Olympics will “act as a spur to help move some of those projects together faster.” This creates a precedent where Angelenos look to the Olympics rather than expecting its government meet needs it should have been meeting all along.

Citizens are encouraged to look to the Olympics rather than expect its government meet needs it should have been meeting all along

This is characteristic of Olympic futurism: longstanding civic deficiencies are turned into forward-looking opportunities. This opens the door for short-sighted solutions touted by other hucksters of the future. For instance, the L.A. bid incorporates Airbnb into its proposal (“Currently, there are over 42,000 Airbnb rooms available for rent from Airbnb hosts within 50 km of the Games Center,” the Olympics bid book notes, “ranging from affordable quality to luxury options and single bedrooms to full houses”) without assessing that company’s adverse impact on housing costs in the region, focusing instead on how well the city has been able to accommodate the “sharing economy.”

This adopts a view of the future already promoted by tech companies, in which “shared” resources offer both convenience and community. But as Jia Tolentino points out in an essay for The New Yorker, this future trades on an old idea about self-reliance, “which makes it more acceptable to applaud an individual for working himself to death than to argue that an individual working himself to death is evidence of a flawed economic system.” People lose economic security in exchange for what tech companies claim is economic independence; labor laws dissolve at the term independent contractor.

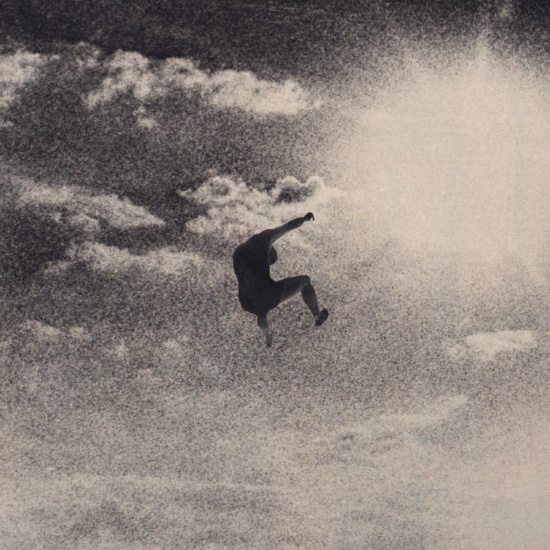

But in the context of Olympic futurism, instead of the image of individuals working themselves to debilitation, we are presented an overriding image of athletes striving for perfection, giving all they have for country and glory.

It is no surprise that the surplus Los Angeles accrued after the 1984 games went back into funding local sports and Olympic training. Not only does that nicely illustrate how the Olympics end up boosting not the host cities but the Games themselves, but it suggests the centrality of idealized athleticism to the Olympic fantasies of the future. As far the International Olympic Committee is concerned, the future appears mainly a matter of clean, innovative arenas to showcase record-breaking feats of competition, strength, poise, and achievement. If there is any vision of economic equality, it is strictly trickle-down. If the athletes are making sacrifices, why can’t a city’s residents?

Athletes, training at the limits of their physical capacity, project the triumph of ends over means as a kind of heroism. Severe injuries — not to mention doping — are common across virtually all Olympic sports. The use of steroids, stimulants, or other drugs to achieve higher athletic performance is technically illegal, but doping scandals are as much an Olympics tradition as the opening ceremonies. Russia recently earned the distinction of being banned from an entire Olympics in response to doping charges stemming from the 2014 Sochi Olympics. Putin’s utopia included high-achieving athletes, regardless of the cost; Olympic futurism imagines there should no cost to pay for achievement. It seeks to project a purity beyond the economic ramifications of competition.

Athletes, training at the limits of their physical capacity, project the triumph of ends over means as a kind of heroism

The Olympics mobilize the body’s ability to push limits and puts it in service of political aims. This was perhaps most explicit with the 1936 Summer Olympics, held in Berlin under the Nazi regime. Commissioned by the IOC to make a documentary of the games, Leni Riefenstahl, who had already made the fascist propaganda film Triumph of the Will, produced Olympia, which translates Nazi ideology to the idiom of sport. Technically a sports documentary, Olympia presents athleticism as a paean to authoritrianism. As Alex von Tunzelmann argued in a 2012 essay for the Guardian, “Riefenstahl’s Olympia subtly underlined a tenet of all authoritarian regimes: that individuals must be turned into machines that act as required, but do not think. At no point do the sportsmen and women in speak.”

Riefenstahl’s camera pans over Greek monuments and cuts to close-ups emphasizing white athletes’ physical power, to evoke an ersatz heritage for the Third Reich and posit a vision of its supposed Aryan future. She cuts together a spectacular image of the Games, wherein the audience, athletes, and Berlin itself are joyous and united over the power of sport. Her use of media technology makes the human body complicit in the way the Games were used to espouse this politicized vision and helped build a legacy of using the Olympics to chart a path toward a “purified” city or country.

Every Olympics broadcast since has borrowed from the techniques Riefenstahl pioneered: tracking the body of gymnasts as they flip upside-down on the still rings, getting close-ups of runners’ faces as they’re about to sprint, positioning the camera below the bar as a high jumper clears it from above. Riefenstahl used editing and sound in Olympia to manipulate the excitement and thrill of the performances, transforming them into fantasies of seamless effort, cutting away with the strenuous and unglamorous components. It created a fantasy of what athleticism leads to — power, success, purity. The presentation of the human body becomes an integral component of a futuristic utopia in which struggle exists only as a conduit for national success.

Olympic promises may now take a tone of civic fortitude, but they perpetuate a system of idolizing the theoretical potential of the Games more than their actual repercussions. A massive media spectacle that showcases a bright and high-tech event packed with audience members and star athletes helps create the image a host city looks for and promises via the Games. The image of success replaces accountability. More environmental policies, revitalization of low-income areas, or expanded job networks take a backseat to an image of athletic power, even though those promises are often necessary to get a city on board with a bid in the first place.

When 2028 finally comes along, Los Angles will be a completely different city. Someone will be the new fastest swimmer, fastest runner, most jaw-droppingly skilled gymnast. But the city will likely still have a crippling homelessness problem, inaccessible transportation, and skyrocketing housing prices. Angelenos will still be walking to their cars on cracked, dangerous sidewalks, trying not to think about the $5.3 billion spent on an image of the future. The Games will come and distract Los Angeles for a moment and inspire another city to reach for its own Olympics-induced salvation. The 2030 Olympics will be just around the corner.