At a consultation with a new therapist, I was asked to describe my family’s medical history. Of my father’s siblings, I said, four have died of heart attacks. They passed suddenly and were mourned without autopsies, but I was told that they complained of chest pain, and that their complaints mounted in the moments approaching death. I was there, at the therapist’s office, because I believed my heart was failing me. Each night I felt it slow, and in the split second before sleep I became convinced that I was dead. I recognized the belief that my body was working against me as delusion, but to the therapist I wanted to substantiate my claims: I come from a long line of people whose hearts have failed them, I said, and I am next of kin.

Last summer my father’s arteries became clogged with a substance the doctors called “plaque.” My father told me that “plaque” is like the film that coats a drain: minor and routine. Into his arms the doctors injected a serum, which he described as “Drano,” but prescription. When the Drano didn’t work because his drains were too clogged, we switched metaphors and his body became a car with motor trouble: he needed spare parts. From his leg the doctors extracted a blood vessel, which they grafted onto his open heart.

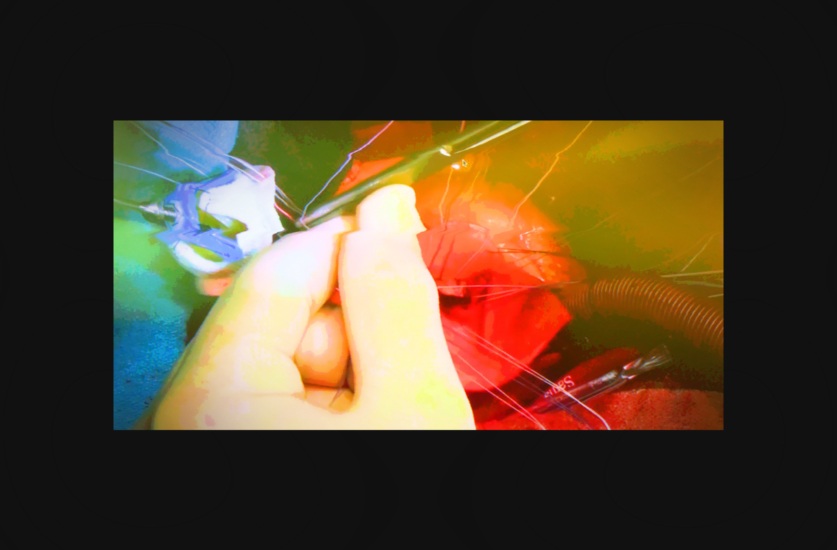

Self-diagnosis teaches patients to speak like doctors, and videos of surgery teach patients to see like them too

Because my father experienced his treatment in an anesthetic haze, his testimony could not account for the incisions his body had sheltered — in the same moment that he registered his inebriation, he woke up. Because I experienced his treatment from the waiting room, I was an unreliable witness: In the time it took for me to eat breakfast, my father had turned into a child. He needed me to feed him lunch.

When we left the hospital, his heart was working well, like a steering wheel newly greased. But neither of us had met the mechanic or been told what to do should the wheel stick again. Our metaphors were becoming mixed, and what we wanted was a representation of the thing itself. I typed “live open heart surgery youtube” into my browser’s search bar and began scanning through the 3,150,000 results, most of which depicted, in real time, the process by which blood flow is redirected around a clogged artery. Here is how it typically goes: First the surgeon cuts into the breastbone, so as to reveal the ailing heart. A machine beats for the ailing heart, and the doctor applies an appendage. A healthy artery is routed along the blocked one, and when the doctors close the incision, the heart, now invisible, beats like new.

If WebMD provides the medical translation for patients’ symptoms — chest pain, shortness of breath, heart palpitations, nausea — YouTube is the theatre in which patients can watch those symptoms be repaired. For every “live” video of open heart surgery, there exists eight videos of “live” nose jobs and 17 videos of “live” c-sections, the vast majority of which have been posted by doctors, hospitals, or third-party promoters. For surgeons who provide elective procedures like breast augmentation, posting videos of successful surgeries is incentivized: Potential patients are more likely to hire a doctor whose work they feel they already know and trust. But for procedures whose function is to save lives, and which are therefore often performed without notice or choice, surgical videos function like a command. Standard patient consent forms now include a video release, which authorizes doctors to share recordings of consultations, examinations, and treatments, all for the express purpose of training their peers. Videos are typically accompanied by a pat narration, which describes the mechanisms by which a featured team of doctors facilitates a successful repair.

Self-diagnosis teaches patients to speak like doctors, and videos of surgery teach patients to see like them too. Because the lexicon of self diagnosis mimics that of professional diagnosis almost exactly, and because the people who control the broadcasts of successful treatment are, for the most part, white men in white suits, articulating pain demands an acquiescence to the language and perspective of medical authorities. “Pain alone cannot be measured by a blood test or ultrasound,” writes Karla Cornejo Villavicencio in the New Inquiry. “It needs to be communicated through some mix of words and performance … both require the physician to need to ‘believe’ that the pain is ‘real.’” Because patients are coded as liars and doctors as priests, the burden of proof is always on those in need of care, and not those who are tasked with providing it. The imperative to make one’s pain manifest obscures the imperative to alleviate that pain with generosity and grace, and as a result of that obfuscation, doctors often leave their patients in the dark.

If “live” videos of surgery grant patients the clinical transparency they are rarely afforded in real life, “secret” videos of surgery — covertly directed by patients themselves — reveal how clinicians speak when permitted to go off script. In Virginia, a colonoscopy patient was scheduled to undergo anesthesia; he brought his phone into the operating room and left it recording should the doctors offered any advice he’d be too drugged-out to take in. But the phone recorded neither tips nor tricks; what he’d missed while sleeping were a series of misdiagnoses intended as jokes at his expense. The doctors suggested a rash on his penis — which they were not supposed to be examining — was Syphilis, then revised the punchline to tuberculosis, and then revised it again so that it was simply a punch: “After five minutes of talking to you during pre-op,” said the anesthesiologist, “I wanted to punch you in the face and man you up a little bit.”

In Houston, Ethel Easter, who is black, suffered from a hiatal hernia that caused, in the space of 24 hours, abdominal attacks, stomach bruising, and a bloody bladder. When she arrived at the hospital, her doctor scheduled her for a laparoscopy, but her appointment, which she hoped would be immediate, was two months away. When she complained, demanding that she needed immediate relief, the doctors told her she had a bad attitude. When she resigned herself to waiting, and the day of her surgery finally arrived, she placed a small recorder in her hair and left it running. When she woke up, hernia repaired, she discovered the doctors had criticized her pre-op demeanor, joked about her bellybutton, and called her by the moniker Precious, which they derived from the 2009 film by the same name.

Speaking precipitates treatment. But for people whose suffering is eclipsed by what medical authorities understand to signal aggression — race, religion, immigration status — speaking is a sign of deceit

Both of these recordings were posted to YouTube, where they now live among colonoscopy and laparoscopy videos posted by doctors who appear very well behaved. Because doctors are arbiters of suffering, they are also arbiters of language. Pain is either diagnosable, dire, or imagined, demarcations that have nothing to do with how it feels and everything to do with how it’s communicated. For people whose hurt is understood by practitioners to be familiar — either because they perform well as patients or because they perform well as “citizens” — speaking precipitates treatment. But for people whose suffering is eclipsed by what medical authorities understand to signal aggression — race, religion, class position, immigration status — speaking is always a sign of deceit.

My father, like his brothers, felt a pain in his chest, and like his brothers, his heart stopped beating. But because he, unlike his brothers, had been granted citizenship and its attendant paraphernalia of safety (affordable healthcare, gym membership, blood pressure medication) the slowing of his heart was controlled by a professional who, hours later, brought him back to life. When the nurse on call in the days after his surgery asked him if the bandages around his calves were too tight, he said “They make me go crazy,” and she ignored him: In Ethiopia he was held in a prison for two years with shackles around his feet. In Romania, where he was one of four black students at a university of thousands, he had to bribe the doctor to speak to him directly. He brought packets of cigarettes to secure an appointment, and a bottle of whiskey to procure a diagnosis. The doctor said his heart was on the right side of his chest, the wrong side, and that he needed a new spleen. That was 1983, the same year the U.S. saw its first nationwide broadcast of a live open heart surgery in a special called The Operation. You are going to die within two months, said the doctor, but still my father lives.