In 1911, the distinguished physicist Ernest Rutherford proposed a new model of the atom. Drawing upon the vastness of the universe, he presented it as a miniature solar system. In this planetary model, tiny electrons whizzed sequentially across vast swathes of empty space while orbiting a “supergiant” nucleus. The Rutherford diagram would become a visual icon, synonymous with the atom itself: a staple of both science classrooms and, in a few more decades, an avalanche of popular culture meant to celebrate — as well as defang — the atom’s capabilities.

While Rutherford’s planetary model was smart, it was not perfect. By 1913, his colleague Niels Bohr had advanced his work to include fixed energy levels. The paradigm shifted again in 1926, when Erwin Schrödinger revealed that electrons do not perform fixed orbits around the nucleus, but instead trace fuzzy likelihood pathways within probability clouds. Schrödinger’s quantum mechanical model revolutionized nuclear physics and remains relevant today. It possesses its own visual beauty, as orbitals unfurl like plump petals across multiple subshells and axes. However, the archetypal depiction of the atomic model is stuck in a time warp: We have long been beguiled by the Rutherford-Bohr model and its retrofuturistic charms. Even today it pops up now and again in contemporary popular culture, secreted within nerdy sitcoms, apocalyptic computer games, and washing powder branding. The atom retains an aesthetic story at its nucleus.

The U.S. intended to dominate the race for thermonuclear weapons — an impossible task without public support

Rutherford kicked off the Atomic Age when he split an atom during an artificial nuclear reaction in 1917. After that, nuclear physics mutated from an abstract field to one with very concrete implications. Nuclear fission of uranium was achieved in 1938; the European physicists fleeing the Nazis at the start of the Second World War were among the first individuals to realize that it could be used as a weapon. In response to their concerns, the British government founded the first formal atomic bomb research project at the University of Birmingham, kicking off the race for the atomic bomb.

At the time, no one nation had the resources or expertise to develop the bomb alone. The 1943 Quebec Agreement facilitated a collaboration between U.S., U.K., and Canada to create the world’s first atomic bomb on the Manhattan Project. At 5:29 am on July 16, 1945, the deafening sound of the Trinity atomic bomb test ricocheted across the mesa in Alamogordo, New Mexico, marking the dawn of nuclear warfare. On August 6 and 9, respectively, America dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing between 110,000 and 210,000 people. The power of the blasts shattered windows to smithereens. Concrete crumbled and became coral pink from radiation exposure. The searing heat of wildfires reduced thousands of wooden buildings to cinders. For many victims, death and cremation occurred concurrently, as their bodies were reduced to ash by the heat of the blast. Those who survived became Hibakusha, “the exposed.” Some survivors were disfigured by their injuries; others faced cancer and chronic disease from radioactive fallout.

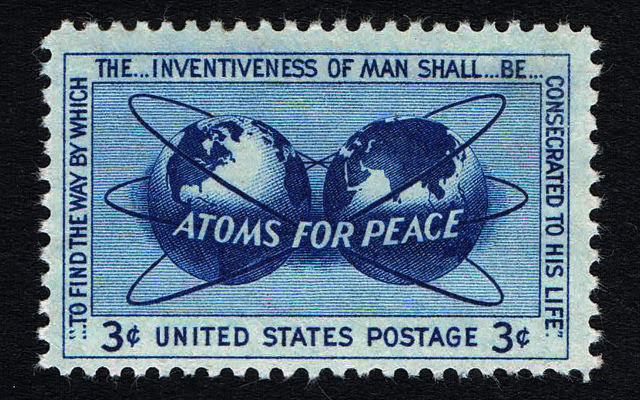

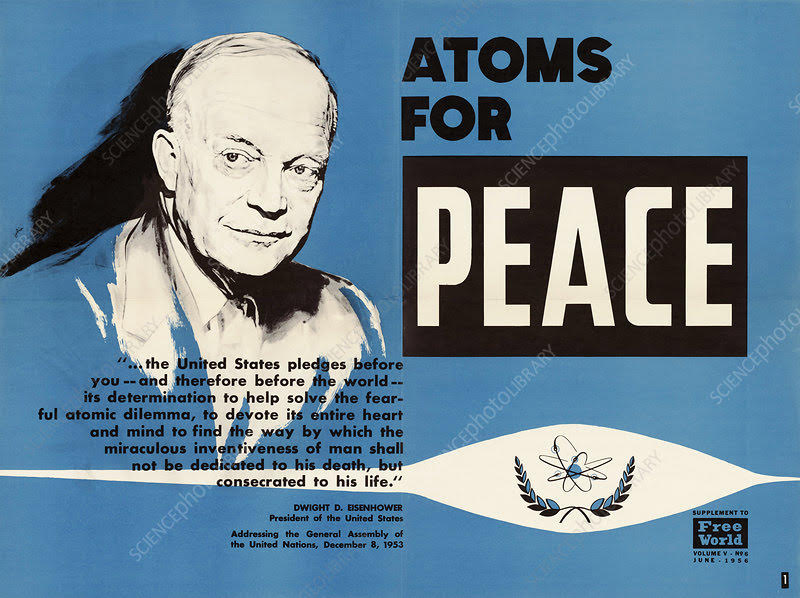

Stamp issued July 1955 based on a 1953 speech delivered by President Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly.

The horrors of Hiroshima were revealed to the public not by the American state, but by New Yorker journalist John Hersey in 1946. Public attitudes towards nuclear weapons began, understandably, to sour, triggering a cultural shift towards anti-nuclear pacifism. A Gallup poll from September 1945 found that only 17 percent of Americans saw the atomic bomb as a “bad thing,” yet by October 1947, the proportion of those who considered the atomic bomb to be bad had grown to 38 percent. This was an uncomfortable situation for America’s nuclear-friendly post-war government. The race for thermonuclear weapons had begun, and the U.S. intended to assert its global dominance — an impossible task without public support. The destructive power of the atom was unquestionable, and it needed a peaceful rebrand. Cultural rehabilitation was provided by the twin powers of President Dwight Eisenhower and the Disney Corporation.

Eisenhower announced the Atoms For Peace program in November 1953, exactly a year after he had ordered the world’s first hydrogen bomb test. Atoms For Peace highlighted the benefits of nuclear technology to energy, medicine, and agriculture; and shared this knowledge internationally, with a catch: The program participant countries were not permitted to develop their own nukes. As the atom’s self-appointed custodian, America purported to take responsibility for the good of humankind. Atoms for Peace initiatives served to naturalize the atom by making it useful and exciting. For example, atomic gardening exposed plants and seeds to ionizing radiation to generate beautiful mutants. Present-day products of the atomic gardening era include the “Star” sweet ruby grapefruit and the “Faraday” tulip. With so much power at hand, anything might be accomplished. The atom, far more than just a symbol of nuclear power, came to stand in for all of science, and for the future itself.

Post-war propaganda permeated popular culture, from the avant-garde to each middle-class TV set

The dangers and possibilities of the Atomic Age were broadcast directly into American post-war homes. This was not an organic process, but part of a meticulously orchestrated state media campaign called Operation Candor. Its purpose was to help the public move forward from Hiroshima and Nagasaki — and to allay their growing fears of Soviet thermonuclear obliteration. In the Disney film Our Friend the Atom, the atom is compared to a genie in a bottle that is capable of great good but also evil. This state-commissioned cartoon is just one example of the work undertaken to promote the atom as an agent of peace. Public focus began to shift from warfare to scientific progress and high technology, offering a clean slate for America’s domestic atomic relationship. The cordial atom’s ascent from the laboratory to the lounge had begun.

From Disney’s Our Friend the Atom (1957)

Post-war propaganda permeated popular culture, from the avant-garde to each middle-class TV set. From the mid-1940s to 1960, as corporate America embraced Atoms for Peace, atomic motifs came to dominate architecture, industrial and commercial design, and fine arts, eventually invading suburban homes. Designers adapted the aesthetics of nuclear physics and chemistry into appealing shapes and patterns, repurposing iconography like Rutherford’s atomic model into desirable products, from clocks to sofas. George Nelson’s iconic 1947 Bubble Lamp Pendant was elegant and mushroom cloud–like. Husband-and-wife design duo Charles and Ray Eames’ striking Small Dot Pattern fabrics and household hang-it-all mimicked molecular structures.

Atomic Age style was characterized by elegant uniform patterns, abstract designs, and cheerful colors, symbolizing hope for the future. The atomic motif in particular represented, but also obscured America’s techno-military ambitions: Despite the atom’s violent wartime history, the organic forms of Atomic Age style were comforting and humanizing. Mutant structures adorned carpets, ceramics, and fabrics; their friendly, cartoonish designs rebranded the atom into something cozy and optimistic.

Eames House of Cards (1952)

While home interiors depicted a blissful atomic future, their occupants lived in an age of revanchist conservatism. American society had become increasingly atomized and patriarchal during this time. Women were important contributors to wartime atomic science: Maria Goeppert-Mayer worked on the Manhattan project, and was awarded a Nobel Prize for her contributions to science by 1963; Leona Woods Marshall Libby worked in Enrico Fermi’s lab at the University of Chicago, where she demonstrated the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. When men returned from war, many women were discouraged from continuing their careers as scientists, technologists, and academics. As mainly white working women became wives in picket-fenced suburbia, they turned to the domestic affairs of the home to regain some control. As such, the demand for Atomic Age style was created by these women’s purchasing decisions. Atomic aesthetics in the home eventually served to “feminize” the atom, further domesticating its image.

The semiotics of the Atomic Age extended to women’s bodies. The fascination with nuclear power inspired fashion, just as it had interior design. As Donna Alexandra Bilak writes, a gown designed by the American couturier Adrian (most famous for Dorothy’s ruby slippers in The Wizard of Oz) offered “a sartorial embodiment of atomic detonation.” Jewelry of the time — accompanying a new sartorial emphasis on curvaceousness and femininity — often featured “a hodgepodge of designs representing explosions, swirls, stars, and sunbursts based on permutations of an atomic theme.” These themes didn’t just represent the optimism surrounding nuclear energy’s potential; they also drew on the awe inspired by its fearsome power. As Bilak notes, even the mushroom cloud was described, at times, in terms of its sublime beauty.

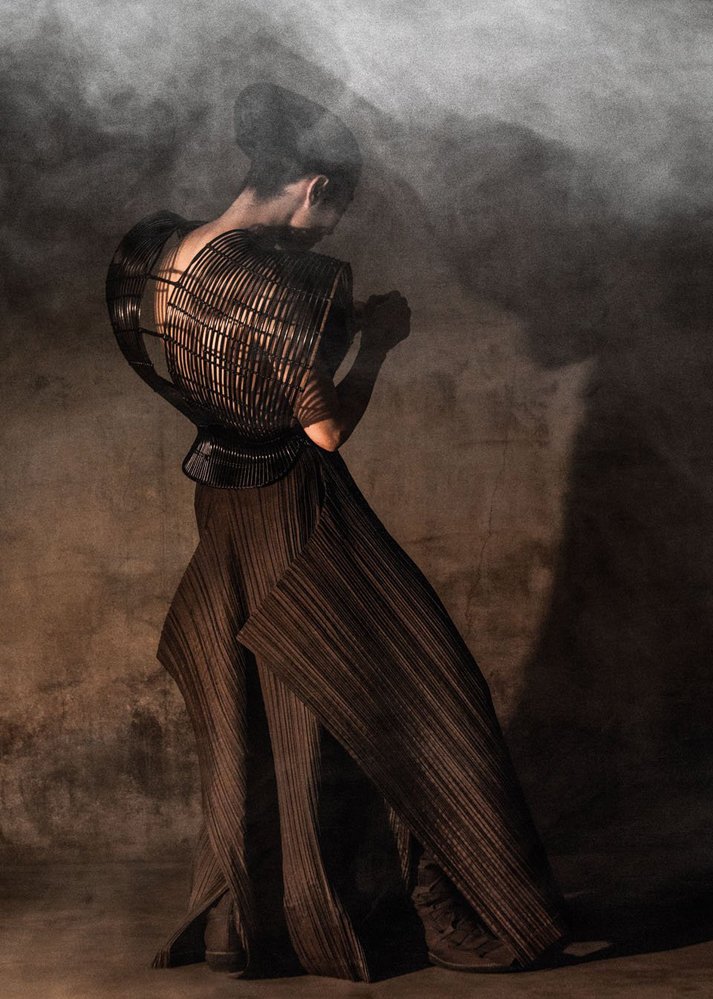

Issey Miyake‘s fame was cemented by his Atomic Age design work in 1960s Paris and New York. Extraordinarily, Miyake was also a Hiroshima atomic bombing survivor, but he avoided discussing his experiences for over 50 years. When he finally decided to speak, he explained in the New York Times that he wished to “think of things that can be created, not destroyed, and that bring beauty and joy.” Perhaps his understanding presents a broader perspective on the joyful and optimistic nature of the time.

Bodice woven with rattan and bamboo from Issey Miyake’s spring 1982 collection.

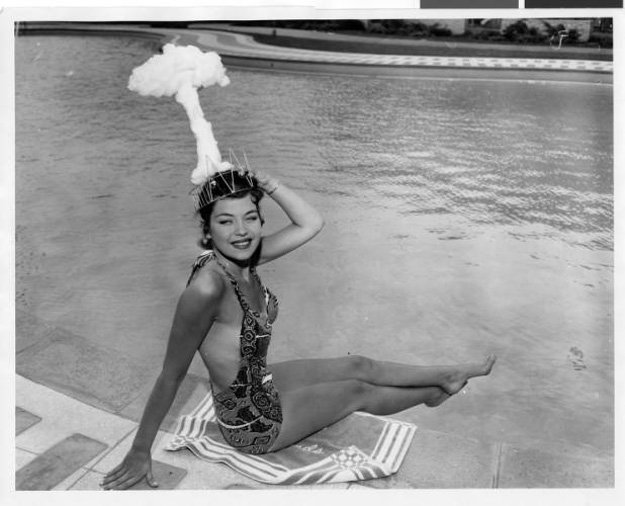

Beauty queens and pin-up girls proliferated after World War II. The new vogue for radioactivity reached pageantry, with new beauty contests celebrating all things nuclear. From Miss Atomic Blast to Miss Atomic Bomb, this cheerful embodiment of lethal nukes has been described variously as commercializing, feminizing, and disarming the atom. By 1955, atomic pageantry had diversified to celebrate and normalize uranium mining and nuclear energy, as Colorado and Utah became home to expansive uranium mining programs. In a contest sponsored by the Uranium Ore Producers Association and the Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce to celebrate Colorado’s uranium mining boom, the winning Miss Atomic Energy was rewarded with a truckload of uranium ore worth approximately $5000 in today’s money — and a trophy in the shape of Rutherford’s iconic atomic model.

The bikini bathing suit debuted in 1946, taking its name from Bikini Atoll, where the U.S. undertook its first nuclear weapon detonations since Hiroshima. Louis Réard’s design was itself derived from a less revealing French design created by Jacques Heim, known as “L’atome.” Both garments played with the semiotics of nuclear warfare. Models were initially scandalized by the bikini’s skimpiness and refused to wear it. By 1951, however, a bikini round had been integrated into the annual Miss World competition, further linking the atom with ideals of feminine beauty.

Linda Lawson at the Sands Hotel pool, early 1950s.

Teresia Teaiwa’s essay “Bikinis and other s/pacific n/oceans” discusses the bikini in light of both the consumption of women’s bodies and the Pacific nuclear weapons tests. Her work explores how the female body was appropriated to divert from nuclear imperialism and to depoliticize the nuclear weapon tests. She writes, “The sexist dynamic the bikini performs — objectification through excessive visibility — inverts the colonial dynamics that have occurred during nuclear testing in the Pacific, objectifying by rendering invisible.”

While America’s Atomic Age design celebrated economic growth and individual prosperity, Britain harnessed techno-scientific aesthetics as it tried to shake off the ravages of the Second World War. The 1951 Festival of Britain aimed to foster a feeling of recovery by sharing Britain’s pivotal creative and scientific contributions with the world. Helen Megaw, a brilliant Cambridge University x-ray crystallographer, cherished the elegance of the patterns that her research generated, and realized that molecular imagery would have mass appeal. As the Patternity Project reports, she headed a consortium of 28 textile designers that produced ceramics, clothing, and soft furnishings with atomic motifs. One particularly striking design featured the molecular structure of beryllium aluminium silicate, also known as beryl.

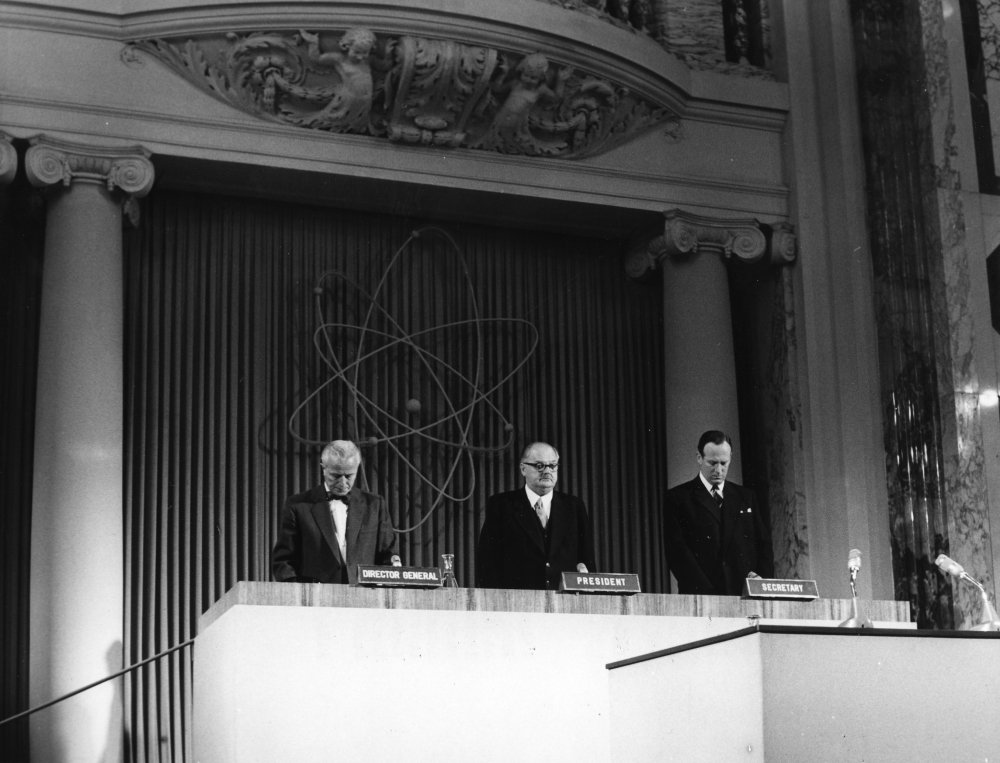

Erik Nitsche for General Dynamics, for the International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy in Geneva (1955)

Thanks to Megaw, this poisonous element quickly found its way to British kitchens in the form of tea towels, plates, and curtains. It would also, eventually, become the emblem of the most important nuclear scientific institution in the world. The International Atomic Energy Agency was formed in 1957 to deliver the US Atoms for Peace Program, and has since become a global regulatory authority. Their first logo included just three electrons; astonishingly, it took a year before someone at the agency pointed out that this logo depicted lithium — a key ingredient in hydrogen bombs. This beautiful but lethal image was unceremoniously updated with an extra electron in 1958. It now depicts the four electrons of the much more stable beryllium whizzing around a central nucleus.

Extra orbital added to emblem at the Second Annual General Conference of the International Atomic Energy Agency (1958)

Most designers were not scientists, and didn’t let a little hazard get in the way of a good logo. This may also be the reason why these images, even today, depict outdated models of the atom, as designers drew upon their schooldays for inspiration. The IAEA’s design history is now older than most of the scientists and policymakers who work under its remit, a friendly relic from a different age. Perhaps it has been retained because it presents an icon from a time of optimism, despite the ongoing threat of nuclear war. Or possibly it’s just an excellent design.

The launch of Sputnik in 1957 coincided with the peak of the Atomic Age. As rockets shot into the sky, women marched for their liberation, and arms control treaties were deployed, our love affair with the atom cooled. It was transplanted in fashionable homes by the sleek asymmetry and futuristic motifs of Space Age style. The space race, like the arms race, was just a new way for countries to embrace military one-upmanship. Graceful satellites and awe-inspiring space walks were the friendly face of a ferocious contest of espionage and missile technology.

Fear and optimism around nuclear science and technology inspired a mid-20th century boom in atomic design, as designers drew upon the symbolic power of the atom to produce motifs and emblems that valorized nuclear technologies. It also exerted a huge influence on both home interiors and women’s bodies, which further helped to domesticate and feminize nuclear technology, masking the prior devastation and threat of nuclear war. Over time, this style came to represent mid-century nostalgia; it developed an ironic charge, as it stood in for values now considered archaic, and an optimism that now seems naive at best. Our world has changed irrevocably, but it is still possible to catch a glimpse of the Atomic Age within contemporary popular culture. From Homer Simpson’s radioactive workplace to The Incredibles, atomic semiotics are still with us.

In some ways the Atomic Age is not unlike the present day. We live in a time of comparable environmental risk and numbing distraction, watching documentaries describing vanishing habitats, as rogue state leaders threaten nuclear annihilation. Skin cancer is becoming more common, and harmful zoonotic diseases such as Covid, malaria, and monkeypox reach further, faster. The Atomic Age reveals how world-changing events can inspire cultural transformation; and how their aesthetics can obscure a necessary urgency.

In memory of Issey Miyake: 1938–2022