“I’m pajama rich,” Kanye rapped in 2010. But, by then, you didn’t have to be rich to spend your days in clothes you could have slept in. Among young, female professionals, Lululemon and its imitators were taking over. Even debt-ridden students and freelancers — or especially students and freelancers — were dressing as if they might at any minute hit the sack or hit the gym. And why not? It wasn’t as if we had fixed schedules.

The size of the market for athleisure — a coinage officially adopted into Merriam-Webster’s lexicon this April — grew five percent each year between 2009 and 2014, from $54 billion to $68 billion. The trend accounted for nearly all growth in the apparel, footwear, and accessories sector during this period. People in American cities were wearing Lululemon, Lucy, and Lorna Jane; Gap Body, Athleta, and Nike everywhere, including to the office. According to a February article in the New York Times, the market may hit $100 billion by the end of 2016. Meanwhile, sales of jeans fell six percent in 2014 alone — the most precipitous drop in more than 30 years. One Business Insider article called it the “Denim Apocalypse.”

Why have fancy workout clothes become the uniform of so many American women? Marshal Cohen, the chief apparel analyst for the market-research firm NPD Group has told reporter after reporter that the reasons are straightforward: The clothes are “comfortable” and suit “a fitness-conscious lifestyle.” But for many wearers, the athletic part of athleisure remains aspirational: Sales of yoga clothes increased 10 times as much as participation in yoga classes over the 2009 to 2014 span, according to the Wall Street Journal. Comfort is not a constant either. As Lululemon founder Chip Wilson infamously said on Bloomberg Television, “Some women’s bodies just actually don’t work in the pants.”

Athleisure offers a physical feeling that corresponds to how we are expected to feel about work, merging work and play, effort and pleasure

It is not simply ease or convenience that puts women in athleisure. The look physically connects us to an ideal. Social psychologists have coined the expression “enclothed cognition” to describe “the systematic influence that clothes have on a wearer’s psychological process.” For instance, a test subject wearing a lab coat becomes more attentive to details than someone not wearing a lab coat. Another experiment found that test subjects wearing what they were told was a “doctor’s coat” did the same, but those wearing an identical garment they had been told was a “painter’s coat” became less attentive.

Simply looking at a lab coat while performing the task had no effect.

The researchers concluded that enclothed cognition derived from two sources: the “physical experience” of wearing a garment and its “symbolic meaning.” Athleisure is trending because it offers a distinctive physical feeling that corresponds to how we are expected to feel about work in an era when “do what you love” is the conventional wisdom about careers. Lululemons announce that for their wearer, life has become frictionless. It clothes us in an ideal that merges work and play to the point where they become indistinguishable, and effort feels like pleasure.

For me, it started with a Spanx. It was the summer of 2009. I was in Minnesota, on the eve of a family wedding, and feeling unsure about my outfit.

“You have a waist from another era,” the saleslady back in New York had gushed, flattering me, when I tried on the high-waisted skirt I was planning to wear. But did I, really? What did that even mean? In the clear light of the Midwest, it looked like an optical illusion, produced by other bulges that the skirt exposed.

My mother pulled a flesh-colored something out of her suitcase that, she laughed, she had to “sausage herself into.”

“Spanx,” she explained.

The next morning I convinced one of my aunts to drive me to Dayton’s. The knockoff I bought fit me like a glove, but more closely than any glove I ever wore.

That night, my cousin was married, and I drank too much and danced too closely with a stranger I kept calling “Mike,” even though I knew he was called Alex. For some reason, in that state, the idea of not being able to remember the name this confident young man kept repeating struck me as funny.

As we swayed, hip to hip, I felt the cling that I now feel in most of my clothing. Held and exposed. Smoothed and protected. The sense of touch is notoriously difficult to describe — hence, begging-the-question words like mouthfeel. But the word for how my casing made me feel was optimized. I was the best lonely girl at a wedding I could be.

The physical sensation of Spanx comes from Lycra, which is another name for spandex. Like many technologies — the internet, for instance — it was a by-product of research funded by the U.S. Army in the middle of the last century. During World War II, chemists at Dupont (itself originally a gunpowder manufacturer) developed rubber-based polymers that could be used to make parachutes capable of resisting rain and heat. After the war, a chemist named Joseph Shivers found that when he took out the rubber, he could make fibers that stretched up to five times their length without losing shape. By 1962, Dupont had commercialized it under the name Fiber K, and soon manufacturers were buying miles of it to make into sportswear and girdles, swimsuits and hosiery. By 1990, spandex was one of the most profitable divisions at the company.

Maybe two years after my cousin’s wedding, my friend Mal told me about Lululemons. We were taking a yoga class at the studio she went to. I have never managed to stick with yoga for the same reason I probably should: I get too impatient. But I still wear Lululemons almost every day.

Spanx and Lululemons share a chemical formula; the spandex they both use offers flexibility to the point of being indestructible. It also embodies the dual nature of that flexibility. Spandex is an anagram of “expands,” but as much as its fibers stretch, they also compress. They offer a kind of comfort, but on the condition that you submit to having your body shaped. Rather, they ask you to commit to shaping it in a certain way.

While Spanx are a secret weapon for managing intractable body parts, Lulus put that effort on proud display, announcing that their wearer is eager to be seen as engaging in constant self-management — toning her ass and thighs and balancing work with “life.” As the “embodied cognition” people might put it, yoga pants let the entire body think that aspiration.

As the Lululemons symbolize aspiration, the spandex enforces the discipline needed to achieve it. Offering convenience, the pants also nag us to exercise. Self-exposure and self-policing meet in a feedback loop. Because these pants only “work” on a certain kind of body, wearing them reminds you to go out and get that body. They encourage you to produce yourself as the body that they ideally display.

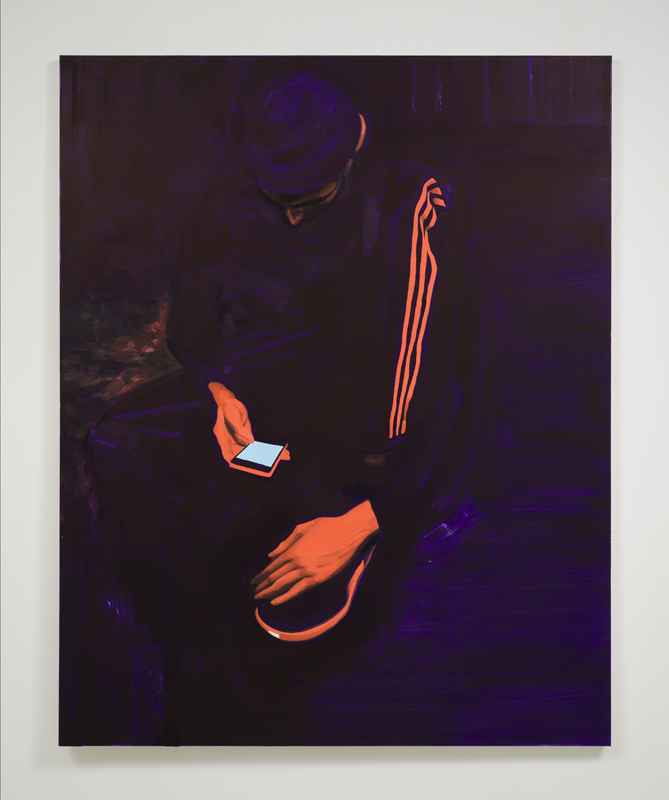

Lululemons suggest an unfussy attitude (“Oh these? These are just gym clothes!”). At the same time, they telegraph that their wearer is driven. “I am dedicated to fitness,” they say, “and I have no time to change.” Yet, wearing these pants at midday hints that you have a flexible schedule. You do not have to go into a traditional office. Or, if you do, you do not feel any pressure to impress. You just might step out for a spinning class or a green juice.

In other words, Lululemons convey status. Like spending a fortune on nutrition, facials, and skin cream so that you can boast that you “only wear lip gloss,” wearing these pants is a form of inconspicuous consumption — particularly when you pair them, as so many women do, with an expensive handbag. In their conspicuous inconspicuousness, as well as their homogeneity, Lululemons recall the “normcore” trend of several years ago. They share the pretense of democratic-ness but leave out the irony. Athleisure humble-brags.

All over San Francisco, I see evidence that the Lululemon class has sexualized the pain involved in becoming your fittest self. The other day I saw a $60 T-shirt for sale on Polk Street. The front read: BARRE WHORE.

Before athleisure, Americans wore denim. Like spandex, denim was said to be comfortable. Like Lululemons, blue jeans crossed boundaries between work and play. Unlike athleisure, however, jeans were first made for men.

Levi Strauss, an immigrant from Bavaria who landed in San Francisco, is credited with being the first manufacturer of modern jeans. In 1873, with a tailor, he filed a patent for a denim pant with “rivets sewn in at the points of strain” — the pockets, crotch, and hip. The goal was to make pants you could wear for years — on horseback and into gold mines or, less romantically, for any sort of manual labor — without ripping them.

Jeans remained working clothes worn by factory hands until around the beginning of World War II, when the uniform was reinvented as an image. When director John Ford put John Wayne in jeans in the 1939 movie Stagecoach, it was to symbolize not drudgery, but freedom through hardship — and the kind of manliness that was supposed to have flourished there in the absence of women. (In the 1870s there were 100 men for every 38 women in California, and the gender ratio would not reach parity until 1950.)

Already in the 1880s, Walt Whitman made fun of the “down-town clerks” he saw flooding in and out of the office buildings of lower Manhattan. They were “a slender and round-shouldered generation, of minute leg, chalky face, and hollow chest.” Their clothes were especially embarrassing. They looked “trig and prim in great glow of shiny boots, clean shirts … tight pantaloons, straps, which seem coming into little fashion again, startling cravats, and hair all soaked and slickery with sickening oils.”

As Western wear, jeans represented a rejection of this white-collar emasculation. Levi’s promised that America was still a place where you could get by on your wits and that if you took risks you could turn dirt to gold. Lady Luck might favor anyone on the frontier — any white man, that is. If jeans were the sartorial symbol of equal opportunity, the democratized work wear of self-made men, racism always tainted their American dream of transcending class. Nineteenth-century satirists mocked the Chinese laborers who came to San Francisco for wearing black pajamas. The Apaches that John Wayne kills sport leather chaps.

Lulus announce someone eager to be seen as engaging in constant self-management — toning her ass and thighs and balancing work with “life.” Yoga pants let the entire body think that aspiration

Fashions changed, but the idea that white-collar work made men effeminate persisted. In the 1950s and 1960s, a growing literature on male malaise — from The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit to Revolutionary Road — attested that the kind of bootlicking required to hold down a salaried job was the opposite of independence. You put up with these humiliations only in order to support your wife and kids. Wearing jeans would never fly with a white-collar boss. A man in jeans thus revolted against domesticity and its demands. On Marlon Brando, James Dean and Elvis, jeans became that paradoxical thing: a uniform of rebellion. As fetishized consumer goods, they became part of the consumer economy — traditionally the domain of housewives and households — even as they symbolized the desire to escape it.

In this same era, women put on jeans to play with the gender expectations men hoped to shore up. A woman in denim seemed slightly cross-dressed; jeans looked like a kind of jaunty drag. Consider Marilyn Monroe in her second-to-last movie, The Misfits (1961), a Western about the end of the Western. Just as the film’s dramatic tension comes from her being unsuited for the cowboy life, the frisson of her look comes from how it combines her hyper-feminine body with manly roughness.

But the ideal female body changes as the needs of capitalism change. The full figure that Marilyn’s jeans hugged broadcast softness and fertility, a person who lived to consume and breed. The shrinking bodies of the 1970s and 1980s suggested a different aspiration: to combine the fragility associated with being female with the drive and self-control required to build a career.

Historically, in western culture, women have been seen as playing the body to the male mind. But the first generation of calorie-counting career girls hoped that they could overcome this history. Get you a body that can do both. Women’s jeans became a fixture in this period because they suited these aspirations and the idealized body that emerged with them.

The new physique expressed the contradictory values of female passivity and masculine ambition. Jeans were ostensibly androgynous garments. This made them particularly well suited for articulating actual gender difference. The 1992 Calvin Klein spreads featuring Mark Wahlberg and Kate Moss highlighted how the ideals of male strength and female fragility could persist even in a presumably equal-opportunity world. The look synthesized them. Because for the vast majority of women, it would take superhero willpower to stay that thin, especially if you were also busy climbing a corporate ladder. The jeans never fit.

Of course, you don’t need to tell any woman who has ever shopped for jeans that they were not made for us. Over the past decade, we may have finally left them behind. This is our progress: In the era of Sheryl Sandberg and Hillary Clinton, we no longer live in thrall to Kate Moss waifishness. In form and in function, athleisure celebrates strong women. It was as if clothes that could stretch to fit a female figure could also make the boundaries between public and private space — between the spheres traditionally understood as male and female, as for work and for sex — more elastic.

American Apparel was the transitional brand. The porny tableaux of lithe young women in monochrome basics that started to crop up on billboards and buses from Brooklyn to Berlin were like Calvin Klein campaigns reshot as sexts. The fact that the models looked like amateurs was precisely what made them titillating. As a dude at a grad school party once put it, “An American Apparel ad promises you could get fucked anywhere. You could get fucked in your youth hostel. You could get fucked at the laundromat.” (When I told him later that I was wearing an American Apparel dress, he waved my embarrassment aside, saying, “I knew that.”)

Next came jeggings — the denim-spandex blend that became popular as American Apparel crashed and burned — and then athleisure, which took the process of “liberating” the female figure from the ill-fitting stiffness of denim to its conclusion. But this liberation is conditional. It retains the superwoman work ethic. A woman dressed in Lululemons looks like she is ready to scream with enthusiasm through a punishing exercise class and then hurry back to the office.

Even as athleisure liberates us from earlier, gender-bound modes of dress they enforce a new code of the body as a constant work in progress. The ideal contemporary subject is a person who is willing to spend all her time being productive. You have to work hard to afford Barre or spin or yoga; at the same time, these efforts energize you to return to work.

In the heyday of John Wayne jeans, the break between work and not-work was clear. Men who worked from 9 to 5 could put on jeans afterward to symbolize rebellion or, at least, their need for respite. It recharged them to return to the office the next day.

In the era of athleisure, time is more ambiguous. When the workday starts or ends, and where work happens, have become less clear. At the same time, selfhood has become an entrepreneurial project, a question of optimizing different activities. The ideal worker in this new regime is female. It is not just that women are more experienced with the kinds of service work and image and emotional work that have largely replaced manual and factory labor in the developed world. It is that women are more accustomed to balancing multiple kinds of demands.

The ideal worker in this new regime — in the era of athleisure — is female. Women are more accustomed to balancing multiple kinds of demands

In April, Beyoncé released a video to announce the release of her new athleisure line, Ivy Park. In it, she delivers a monologue over a montage of her exercise routine,explaining that the brand name comes from the park where her father used to make her exercise every morning as a child. “I remember wanting to stop, but I would push myself to keep going,” she says. “It taught me discipline.” Of course, the Ivy part comes from the name of her daughter.

In the voiceover, Beyoncé demonstrates how she shifts easily between public and private mode, between the work of work and the work of life: “There are things I’m still afraid of. When I have to conquer those things, I go back to that park. Before I hit the stage, I went back to that park. When it was time for me to give birth, I went back to that park.” The video cuts to an image of her giving Blue Ivy a piggyback ride. It’s a typically understated rebuttal to the haters who say that Beyoncé did not gestate her child. But it also suggests that the drive her father instilled in her applies equally to her work as a pop star and to the private tasks of being a mother. To compete at the top, the empowered woman must be willing to work anytime and anywhere.

“The park became my strength,” Beyoncé concludes. “The park became a state of mind. Where’s your park?”

If the default gender of athleisure is female, men seem to know what is up. “You’re in spandex country now,” an Uber driver crowed to my sister as he dropped her off in the Marina neighborhood of San Francisco recently. “You bring your stretchy pants?” I have heard more than one man refer to Lululemons as “those pants that make every girl’s ass look good.” I meet a petite philosophy professor who tells me about going on a few dates with a man who asked her to start wearing Lululemons, for this reason, on date three.

The past 10 years have seen a resurgence of the ass as the key femme trait. If “Baby Got Back” came out now, it would make no sense: No magazine is telling anyone that flat butts are the thing. On the contrary: Blake Lively is quoting Sir Mix-A-Lot re: her own ass, on the red carpet at the Oscars: “LA face and an Oakland booty,” she posted on Instagram. Sir Mix-A-Lot defended her against those who criticized the post for being racially insensitive. (“I checked it out, and looked at it and I was kind of … I liked it. You know I like stuff like that,” he told the Hollywood Reporter.) “Booty celebrity” Jen Selter has earned 9.5 million followers by posting photos of her posterior. Most show her doing squats in the garment best suited to showcase them: athleisure leggings.

To look at Beyoncé after looking at, say, Kate Moss gives one hope that our culture is embracing a wider array of body types and sex symbols than it once did — and giving women more latitude in the process. The figures of Beyoncé, Nicki Minaj, and Kim Kardashian no longer look as starved as those of Calvin Klein models. Nonetheless, they too demand discipline to maintain. A new generation of strong women are still being encouraged to direct their energies inward, to transform their bodies into fetishes. Beyoncé says she exercises two hours per day. Jennifer Lopez — whose private trainer told the press that he has never met anyone who works so hard — took out insurance on her ass. We can have a range of female bodies, so long as they are all commodities.

And, of course, so long as they are firmly located on one side of a cisgender binary. While I am writing this essay, Facebook starts showing me ads for Lululemon for men. Ironically, these ads describe the project of getting a man into exercise clothes as one more thing for women to do. The man in the ad that I see most often looks like Chris Hemsworth. In him, a Mark Wahlberg build meets long gold hair. If The Misfits posed the Woman in Jeans as a kind of drag performer, this guy is a gender-flipped Marilyn, the man who can be dragooned into buying outrageously expensive pants to maintain himself.

“We’ll help you help him,” the ad reads. “Our shorts just got the ABC (anti-ball crushing) upgrade, giving him the freedom from unnecessary adjustments.”

Markets need to expand. It makes sense that companies would want to develop a His version of the garment of choice for the ambitious and Bootylicious. But Lululemon for men has yet to catch on, and most of my male friends insist it never will. When I ask why, they are blunt: “You can’t wear those pants if you have a dick.”