It has always struck me as ironic that audiophiles are often mediocre listeners. Careful listening to music defines the audiophile’s identity, yet conversations with them can be frustrating affairs. They believe themselves to hold special insights into sound, which they impart with little prompting: knowledge of the best books about audio fidelity, of the highest quality recordings, of historic hi-fi landmarks, of the best speakers, speaker cables, speaker polish. The audiophile tends toward monologues, impervious to disinterest — or dissent.

When Baudrillard, in his 1979 book Seduction, personifies hi-fi recording, he may as well be describing the audiophile. Such recording, he argues, “gives you so much — color, luster, sex, all in high fidelity, and with all the accents (that’s life!) — that you have nothing to add, that is to say, nothing to give in exchange. Absolute repression: by giving you a little too much one takes away everything. Beware of what has been so well ‘rendered,’ when it is being returned to you without you ever having given it!”

This description of an excessive information giver evokes another figure: the mansplainer, a person who speaks without purpose, pause, or perspective, offering unsolicited explanations that overwhelm bystanders. If women are conventionally represented as patient listeners who accommodate such insensitivity, men are positioned as those compelled to inform, evaluate, and explain. Of this character type, the audiophile is the most intriguing iteration because he is the most ironic: a person who loves sound yet doesn’t listen.

In popular culture, the trope of men as empowered speakers takes on a number of forms. Essayist Alana Massey has sketched a portrait of the “sugar daddy,” a powerful man who hires young women not only for sex but for their willingness to listen to him talk about himself. The sugar daddy, in Massey’s description, has few valuable things to say; he will expound only on “his own tedious mythology.” His desire to lecture, however, drives him to speak for the simple pleasure of being heard.

Audiophiles, like catcallers, are often unaware of the resonance of their own voice

This portrait resonates with the figure of the oppressive teacher critiqued by educator Paulo Freire. In Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968), Freire theorizes education in terms of listening. He argues that bad educational practice forces students to behave as docile listening subjects who can be filled with knowledge, as though they were empty vessels before receiving it. During this process, which “anesthetizes and inhibits” the students’ creativity, the lecturer speaks as if reality were static and predictable, draining words of their concreteness until they become a “hollow, alienated, and alienating verbosity.”

In a sense, such words function like catcalls; they are comments presented as valuable insights that come off more like surveillance, threat, or ridicule. The catcaller feels authorized by his social position to speak without a filter, evaluating subjects he only dimly comprehends. Reflecting on the weariness many women feel at this attention, Autumn Whitefield-Madrano writes, “I suppose what I’d want to happen is for men to just know what they’re saying when they say it — or rather, for men to know what women hear when they speak. To know that the two are not the same.” Audiophiles, like catcallers, are often unaware of the resonance of their own voice.

Listening differs from hearing in that listening takes account of the “situation of audition,” in anthropologist Paul Carter’s words. The implications of aural gestures emerge neither at the point of intention nor reception, but somewhere in the space between, amid a tangle of waves in air. For Freire, a liberating model of education involves not merely transferals of information, but conscientização: shared critical consciousness between teacher and student, a tug of war between the act of listening and the act of listening in the world.

For writers and theorists, acoustics have long been a choice metaphor for polite conversation. Roland Barthes asks in A Lover’s Discourse: “The perfect interlocutor, the friend, is he not the one who constructs around you the greatest possible resonance?” More than just an act of friendship, listening well among strangers is an ethical imperative, with rules as amorphous as sound itself.

Once, I spoke to a high-fidelity audio-equipment expert about my research on social histories of listening. I had written about the significance of our memories and moods in evaluations of audio fidelity, a critical take on empiricism that was dismissed as “provocative” in conversations among audio enthusiasts on web forums. When this expert asked me what I thought about the sexist subtext on those forums, I defended audiophiles. I chalked up their more blatant prejudices to a misguided earnestness and identified with their analytical style of thinking, their attention to detail, and their love of music. Nonetheless, my interlocutor chastised me for being sexist when I stood up for myself.

This defensive inversion, calling reverse discrimination at the slightest sign of critique, was in character for the audiophile, who is known for his chauvinism. Hi-fi enthusiast Ralph Ellison acknowledged as much in his canonic essay on urban listening, “Living With Music” (1955). He recounts his arrogant “plunge into electronics,” during which obsessive listening to hi-fi records led to a volume war between his prized phonograph and his upstairs neighbor, a vocalist. But the story ends with him turning down his records to better hear his neighbor’s singing, which came to move him greatly: “I was forced to listen, and in listening I soon became involved to the point of identification.” This is audiophilia at its empathetic best.

More often, the audiophile’s hypersensitivity leads them to balk at being regarded as anything other than a foremost expert. This competitiveness has led male audiophiles to defend their turf in a way that excludes women. “Women broadly have too much sense to be audiophiles,” wrote journalist Jonathan Margolis last year, suggesting that a feminine aesthetic is incompatible with the excessive consumption associated with appreciation of high-quality sound. From this view, the fact that women make up less than five percent of sound engineers and producers — the professionals who control how music is documented and distributed — is a sign of female practicality, not women’s systematic discouragement from participation in the field.

More than just an act of friendship, listening well among strangers is an ethical imperative, with rules as amorphous as sound itself

False flattery of women as sensible, like a catcall, conceals essentializing assumptions about gender — in this case, a “boys with toys” mind-set that imagines women as domestic managers intent on reining in their husbands’ childish shopping habits. In a 1954 article for High Fidelity, audiophile Thomas I. Lucci described his invention of a stereo system enclosed inside a large box in which a man could sit to tune out his family. But, as Lucci stressed, this immersive cube would have a crack that allows one’s wife to “slip you a sandwich now and then.” With this legacy of idealized sloth in mind, perhaps we should conclude it was too much trouble for Margolis to interview any living female audio experts for his piece on audiophilia. (Susan Rogers, engineer of Prince’s Purple Rain, maybe had too much sense to comment.)

The critical underrepresentation of women in conversations about audio, then, is no surprise. It’s clear why some aspects of the popular audio-recording website gearslutz.com might turn women off to the field as defined by wealthy men. Beyond the site’s asinine URL, the equivalences between price and quality drawn all over the site’s message boards are indicative of the community’s complacency. On one of the site’s forums, “The Moan Zone,” the moderators emphasize that no discussion of politics or religion is allowed. No feminism, no feelings, no cults — except that of unbridled consumerism.

The audiophiles’ refrain is that we all could be better listeners if only we owned gear as good as theirs. Case in point: A recent promotional video called “Lossless Explained,” made by the streaming provider Tidal in hopes of persuading prospective customers to sign up for its $19.99-a-month “high fidelity” service. The video intends to teach listeners how to better hear audio quality — something one might think would be self-evident, even to untrained ears — in order to convince them this higher quality is worth a higher price.

First, the video must make listeners doubt their ability to perceive distinctions between recorded sounds. Tidal presumes we can’t tell the difference between MP3s and “lossless” sound, and that we need a video with subtitles to explain the inadequacies of what we are hearing — and how we hear it. The first musical example plays with a frame that reads: “This is an MP3. The sound lacks liveliness.” As the audio track continues and transitions to a supposedly “higher quality” passage, the texted visuals force a comparison on us: “This is lossless sound quality. A fully detailed, richer sound.”

The arguably negligible differences in sound between the two passages are exaggerated by what is clearly a difference in quality of musical performance. The actual live performance of the purportedly low-quality MP3 portion of the track is sloppy, featuring intentionally cacophonous musicianship. By contrast, the lossless portion is tight and well-performed, producing clarity of rhythm and time feel. In other words, the video explicitly insists we should be hearing distinctions in audio quality, even as such distinctions are emphasized by different styles of instrumental performance and not styles of recording, compression, and playback. Rather than capture supposedly empirical differences in sound quality that would presumably be content agnostic, the musicians perform an idea of audio fidelity.

Tidal’s advertisement exemplifies the mansplainer’s lack of self-awareness: The video’s premise is flawed, the information delivered is misleading if not entirely inaccurate, and the imagined audience is openly belittled. Like an audiophile, a sugar daddy, or a dull pedagogue, the video’s makers assume listeners can’t or won’t appreciate the object under explanation, but they proceed to explain anyway. Like catcallers, they tell us what we should be hearing without knowing what they are really saying about us. The final frame of the video reads: “Ready to hear it as it should sound?”

An attentive listener to the Tidal video finishes it feeling disoriented and gaslit. An inattentive listener might be seduced by the advertisement’s surreal performance, enough to proceed to pay the $19.99 monthly fee. According to Billboard, as of March 2016, Tidal’s “hi-fi” service was accessed by 1.35 million subscribers.

Although listening closely is widely considered a laudable act, listening inevitably involves restraint. Writing during the Cold War, Jacques Derrida, in The Ear of the Other, warned readers against listening too well lest they become subjects of totalitarian rule. He, in a reversal of Baudrillard, uses the metaphor of a “high-fidelity receiver”:

The hypocritical hound whispers in your ear through his educational systems, which are actually acoustic or acromatic devices. Your ears grow larger and you turn into long-eared asses when, instead of listening with small, finely tuned ears and obeying the best master and the best of leaders, you think you are free and autonomous with respect to the State … Having become all ears for this phonograph dog, you transform yourself into a high-fidelity receiver.

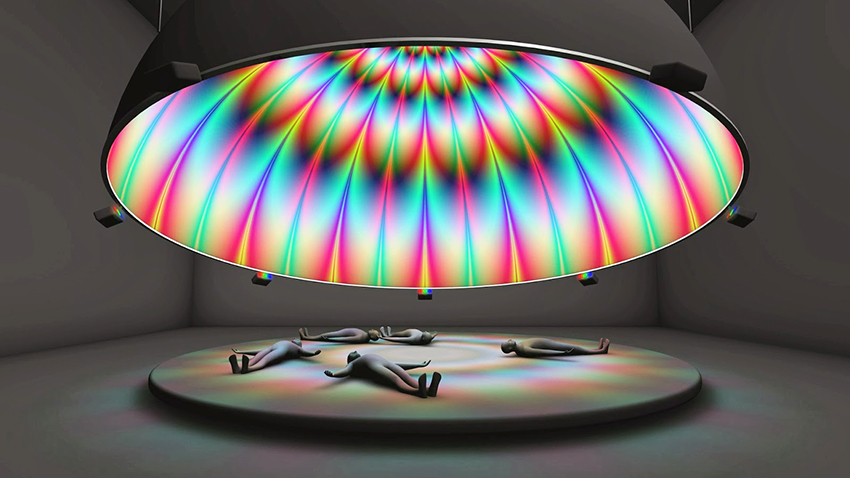

Historically, sound’s multi-directionality and capacity to enclose listeners has made it seem particularly capable of systemic coercion, brainwashing. In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to the way sound in built environments structures social life. Capitalizing on the capacity for sound to invisibly alter consciousness, corporations such as Mood Media (formerly Muzak) teach businesses how to use background music in shops to covertly encourage increased consumption. “The sound kind of creeps in; you can’t turn off your ears,” said Craig Dykers, architect of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, describing how his team exploited acoustic properties when designing the museum, emphasizing certain frequencies to influence visitors’ walking pace.

Unlike eyes, ears don’t close. To protect ourselves, we must tune things out, and our choices about what to sacrifice are often fraught

Unlike eyes, ears don’t close. Listening leaves individuals especially susceptible to external influence. Many good listeners find this vulnerability exhilarating; they let mansplainers finish for the pleasures listening brings and the insights they absorb. In John Cage’s formulation, listening to anything at all can render it artful by virtue of it being fully heard. But interest easily lapses into false curiosity, unwarranted attention offered to those who don’t deserve it. With this in mind, a mansplainer’s speech (described by Julia Baird as a “manalogue”) could be considered a form of coercion that exploits the labor of patient listeners. To protect ourselves, we must tune things out, and our choices about what to sacrifice are often fraught.

Many sounds in the world are best avoided: irritable trolls, tired children, raving loons. To be “tone-deaf” is to speak eloquently about the wrong subjects or poorly about the right ones, targeting someone else’s audience or intervening in their conversation; it is to miss the point entirely. Days after the shooting at Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, one of my relatives erupted into an online tirade, blaming queers everywhere for all of modernity’s discontents. At that moment, I’m not sure whether the mute button on my social media profile functioned more like a fist or a form of prayer.

To listen ethically is to engage the ambiguity between what we choose to disregard and what we need to hear. Although it’s probably wise to follow Derrida’s advice to listen with “small, finely tuned ears,” reflexive auto-curation can be cloistering if it becomes a way of life. Masking, one of the sonic principles underlying audio compression, enables the manipulation of frequencies deemed inaudible on a digital audio file, which makes the files manageable by saving space. Convenient accessibility to the music depends upon the exclusion of what is deemed expendable, based on generalizations about the typical human ear. Audiophiles debate whether the missing frequencies can be detected, which raises a question: Can we resist what we can’t hear, or what we simply ignore?

In recent years, widespread accessibility to noise-canceling headphones has led to an association of the device with certain types of listeners: millennial aesthetes, estranged from the communities through which they commute. For philosopher Michel Serres, dialogue is defined by the exclusion of an imagined third party, “noise,” from a pair. And headphones — like all technologies of listening, be it a gadget or a mode of etiquette — are often used to cancel noise without starting conversation in any meaningful sense, defending their users against histories of conflict and inconvenient realities.

Although headphones often work like antlers, they can also be used as hearing aids. Prior to the commercialization of the loudspeaker in the 1920s, headphones were the most common means of listening to gramophone discs and radio. Far from an isolating device, they were used by heads of household to listen to the narratives of radio broadcasts, which would then be relayed to the rest of the family, gathered around the receiver. If this rapt fascination, applied in the wrong context, is exactly what encourages mansplainers to continue, this should lead us to give up on mansplainers, not on the act of listening itself. Close listening can help attune us to the world and to each other.

When the din of political spectacle becomes intolerable, silence can feel like a form of refuge. On a metaphorical level, a loss of hearing may seem welcome, but it is a luxury to treat noise as a metaphor. The World Health Organization recently announced that 1.1 billion people worldwide are at risk of partial or full hearing loss, a serious threat posed by excessive and prolonged exposure to loud environments. Although noise might ultimately overwhelm us, we can nonetheless resist deafening ourselves to what challenges and moves us most.