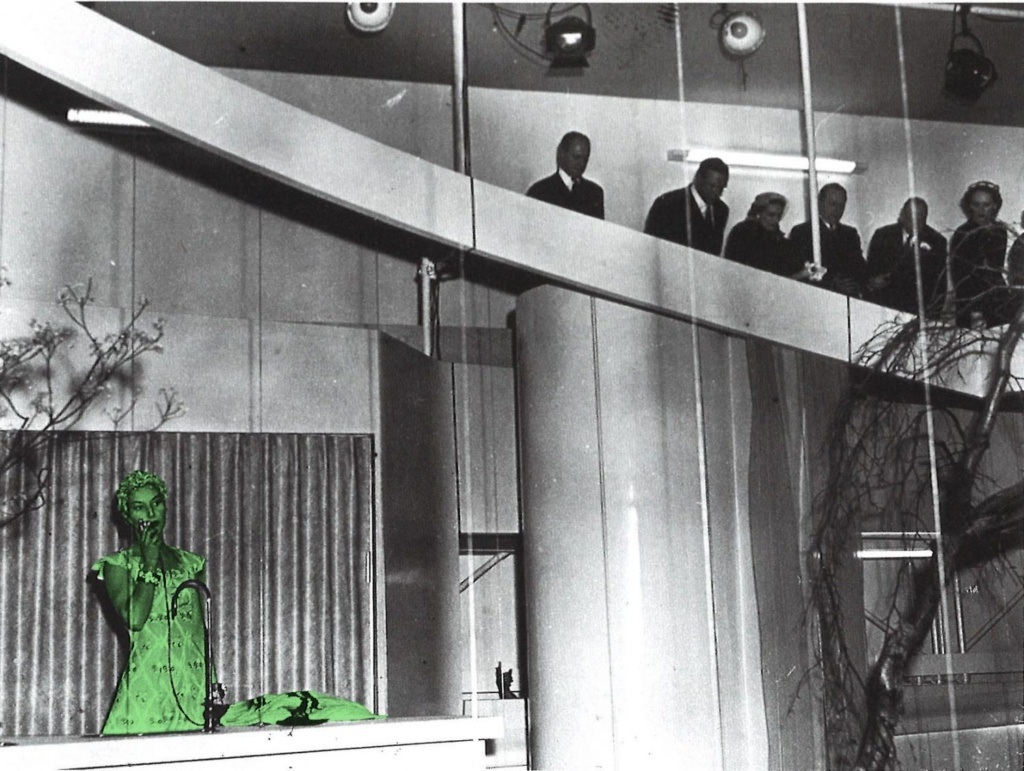

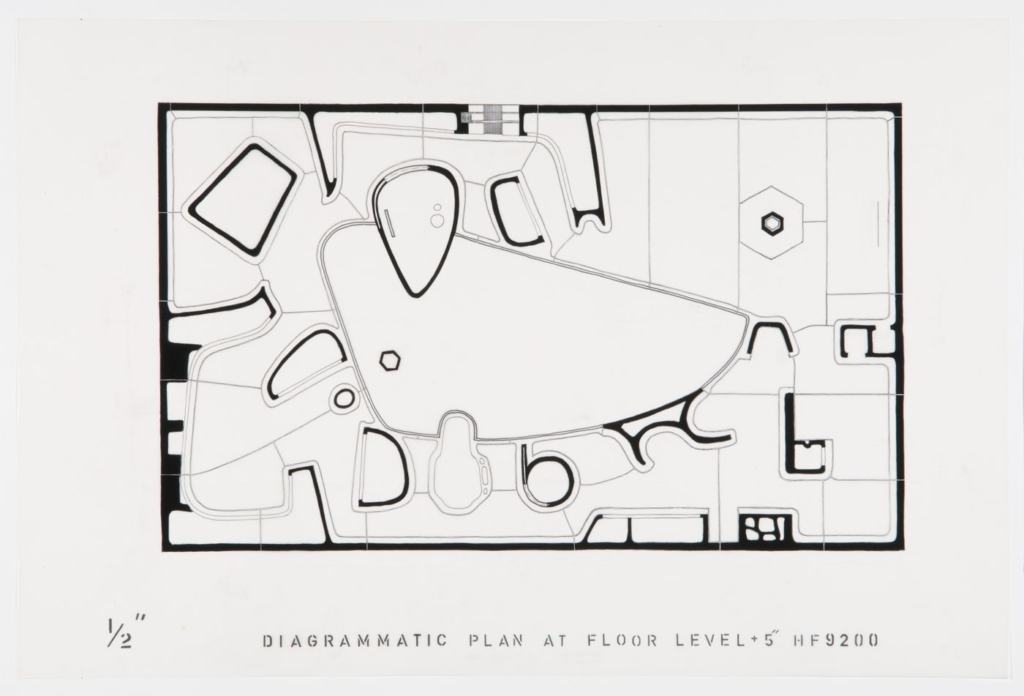

In 1956, Alison and Peter Smithson designed the House of the Future, an architectural installation which was later displayed at the Daily Mail’s annual Ideal Home Exhibition. The installation offered a vision of the future styled for the modern childless couple of 1981. The house was modest in size, with rooms that flowed continuously into the next, amorphous and all-encompassing like a cave. A product of post-war discourse and the early days of the Space Age, its aesthetics emphasized the empowering and alienating effects of technological advancement, while rooted in a recognizable, domestic past.

The house was marketed as an ideal “household life,” but the structure itself revealed a different intention: to cut off the outside world altogether, protecting its inhabitants from external threats while preserving a scene of domestic bliss. The house was fortified with two outer walls — a box within a box — with few exterior windows, allowing for identical houses to be developed side by side. The main source of natural light came from an oddly shaped, fully enclosed courtyard in the building’s center. The home was also equipped with a hermetically sealed, sliding front door; air conditioned interiors; a wired microphone system; sanitary amenities such as a self-cleaning bathroom; and an enclosed courtyard of “unbreathed air” (in the words of architecture historian Beatriz Colomina). What was being advertised as a modernist patio home was really a science fiction mock-up of the Cold War safe-house.

The human body was becoming a paranoiac site, and the House of the Future was a large-scale immune system

The fears disseminated to the Western population during the Cold War era strongly influenced its architecture: nuclear threat was inevitable, and survivability depended on cover. The importance of “preparedness” in the American consciousness of the 1950s and ’60s played out in the ideological construction of domestic space as a bunker site. The Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization placed emphasis on buildings that could not only survive an atomic blast, but also provide shelter from nuclear fallout, and provided installation instructions for double-walled or underground concrete and metal shelters. Modernism’s glass structures gave way to windowless concrete fortification. And yet domestic bunkers often integrated modernist design features meant to offer citizens comfort and psychological reassurance — encouraging an imaginative process of preparing for destruction, while promising an unchanged lifestyle in the face of nuclear war.

Cold War fears were also attuned to the enemy within. Critic Daryl Ogden has written about how the rhetoric of 1940s and ’50s immunology and virology forged a conceptual link between the fear of illness and fears of communist infiltration and invasion. In the 1949 publication The Production of Antibodies, virologists Frank Fenner and Frank McFarlane Burnet proposed a theory that mirrored many post-World War II anxieties around communist traitors within the body politic, asserting that the body’s immune system distinguished “self” from “non-self.” Ogden notes that for the body to succeed against disease, it had to do two things: 1) eliminate “effete” self-marked cells that weakened the body’s own defenses; and 2) destroy non-self biological agents. This rhetoric warned Americans of formidable enemies within the body that appeared — like communist sympathizers — to constitute the Self but were, in fact, the Other. The human body was becoming a paranoiac site, predicated on fear of disloyalty and subversion from within the body itself.

The House of the Future reflected this paranoia. The structure operated as a large-scale immune system: Similar to a submarine, the house had only one point of entry, which was carefully controlled and maneuvered from the inside. The embedded microphone system allowed its inhabitants to make contact with outside visitors without having to invite them indoors. Food was stored in air-tight, sealed containers within the hollow walls of the house, along with rainwater collected from the roof, allowing inhabitants to live self-sufficiently. Beatriz Colomina recounts that the Smithons promoted a particular feature where “all food [was] bombarded with gamma rays — an atomic byproduct to kill all bacteria,” remarking that use of terms like bombardment and atomic rays mimicked the language of war. The Cold War scientific paradigm, supported by the rhetoric of virology and immunology alongside looming global warfare, considered the body a vulnerable site for invasion and contamination against which all defenses were required. As an architectural object, the House of the Future embodied the Cold War citizen, concerned with the banishment of insidious and unseen terrors that could infect the body and attack from within.

The analogy between body and building has been a constant theme throughout architectural history. For centuries, architects — long before there was even such a title — have been using the human body as a generative model, reflecting the scientific paradigms of their eras. De Architectura (published as Ten Books on Architecture after its “rediscovery” during the Renaissance) was written by Roman architect Vitruvius around 15-20 BCE, and is considered one of the most influential texts in Western architecture. Vitruvius discussed proper symmetry and proportion as related to the building of temples. He believed that the proportions and measurements of the human body, which was divinely created, were perfect and correct; therefore, a properly constructed temple should reflect and relate to its parts. In this way, the body was seen as a living rule-book (the “golden ratio”), containing the fixed and faultless laws set down by nature. In the Modernist era, Le Corbusier, inspired by the technical precision of mechanical engineering, furthered this tradition by using the golden ratio against the mathematical proportions of the contemporary human body — more precisely, the body of a six-foot Western man with his arm outstretched above his head — to improve both the appearance and function of architecture and design. With this, Le Corbusier developed two new vertical measurements which he implemented as a principle of proportion to make redundant both the imperial and metric systems. Le Corbusier’s infamous modular buildings and social housing complexes, which implemented these measurements, revolutionized modern architecture’s rectilinear forms, with open interiors and “weightless” structures.

Notions of the body have shifted significantly since the Cold War: The body is increasingly hard to dichotomize into “self” and “other,” and more apparently an interconnected network of living and nonliving entities. This has upended architectural ideas of the dwelling: from something that banishes the outside world, to something that invites it in; and from an inorganic shell, to a hybridization of the body itself.

In her essay Air of Our Closed World, architecture scholar Ala Roushan highlights the parallels and differences between our current era and that of the Cold War. Similar to the threat of Cold War nuclear extinction, Covid-19 has urged citizens to seal themselves indoors in order to survive; but our current network technologies tether disparate communities together, solidifying our dependencies on digital technology as an essential part of life. “Sixty-four years after the House of the Future, our own homes function much like the theatrical space of Smithson’s machine — replacing the physical gaze with informatic exchanges as a register of our existence,” she writes. “We no longer breathe together, and the shared breath is now replaced with exchanges of digital information. The bubble becomes an echo chamber.”

The house embodied the Cold War citizen, concerned with the banishment of insidious attackers from within

As wireless communication networks replace material networks, the boundaries between human and nonhuman have blurred. It could be said that the contemporary human body has two selves: one of the flesh, and the other of a digital “body” consisting of biometric information, preferences, moods, habits, and schedules. The deep integration between physical and digital has made it more difficult to categorically say what belongs to the Self and what belongs to the Other. The Covid-19 crisis has only intensified the search for a new understanding of the human body, one that acknowledges the need to learn from codependent networks beyond the human species, be they technological or environmental.

Such is the posthuman ethos, which moves the human being further away from the center of inquiry. The guiding principles of posthumanism began to take shape within the mathematical sciences after World War II, which focused on the technological engineering of communication, feedback, and coding mechanisms to facilitate transmissions in organic and inorganic systems. In the 1960s, aerospace engineers developed a cybernetic organism, also known as the “cyborg”: a self-regulating human-machine system capable of enabling human life in new environments. Feminist theorist Donna Haraway later popularized the term in her 1985 essay “A Cyborg Manifesto,” invoking the cyborg as a sophisticated blend of body and machine that challenges the organic composition of the human.

Central to the construction of the cyborg are informational pathways connecting the organic body to its prosthetic extensions. In How We Became Posthuman, Katherine Hayles notes that this conceives information as a “disembodied entity that can flow between carbon-based organic components and silicon-based electronic components to make protein and silicon operate as a single system.” Posthuman theory hypothesizes that humans as a species have created a new technological environment in which we can no longer operate independently as living organisms. It widely suggests that the human body is no longer compatible with its technological surroundings, and that we have reached an evolutionary endpoint where the next logical stage of adaptation is for the organic to assimilate to the mechanic.

Concurrent with the development of networked technologies, architecture has begun to shift from something protective — a body’s second skin — toward something that is part of an interconnected system with the surrounding environment, blurring the distinction between home and occupant. While most of our current architecture is still rooted in older spatial imaginaries reminiscent of the Vitruvian or modular body, speculative prototypes, rooted in posthuman thinking, are accelerating ideas for how the built environment might evolve.

As far back as the 1960s, prototypes of posthuman architecture emerged, with visions of new worlds filled with technological wonders. Many of these visions prefigured the potential of the network, exploring it as a notion that could fundamentally transform our sense of space and the built environment. The Fun Palace, designed by Cedric Price from 1959 to 1961, was not a building in any conventional sense, but instead a socially interactive machine. Conceived of as a new kind of cultural center, the structure was intended to be a constantly changing matrix wired with the latest information technology. Although the structure was never realized, the concept was to invite visitors to assemble movable, prefabricated walls, platforms, and floors, to create their own art space for theater productions, exhibitions, and performances of all kinds. What ultimately distinguished The Fun Palace from other projects of the time was its embrace of cybernetic thought. Electronic sensors and response terminals would collect information on leisure preferences. The computational power of an IBM 360-30 mainframe computer would detect clusters of trends, providing the specification for spatial modification. Not simply responsive to human need, The Fun Palace would use information to anticipate behavior.

Architecture has begun to shift from something protective toward something that is part of an interconnected system

The Fun Palace predicted a reality we’ve come to accept. With this project, architecture dissolved into the technological gadgetry that extends our limbs and senses. The structure was imagined as an interface between us and the world, defining space not by enclosure but by mediation. The models of space proposed by posthuman and cybernetic architecture shift our understanding of architecture itself, from the static, autonomous shelter to something dynamic and ever-changing.

In more recent years, a new generation of interactive technologies has been rapidly emerging within contemporary architecture, integrating machine learning, emotional computational systems and synthetic biology reactions into built structures. Hylozoic Ground by Philip Beesley was a Canadian experimental installation constructed for the 2010 Venice Biennale of Architecture. It created a new kind of responsive architecture, simulating the structure of earth itself. Hyperbolic meshworks were organized into over-hanging webs, presenting as a “geotextile terrain,” exhibiting qualities of a plant or fungus-like system. An array of mechanisms allowed these webs to breathe, shift, and move in relationship to passersby. Dense groves of frond-like “breathing” pores and whiskers, organized in clusters, communicated to one another — like a swarm of insects, or a coral reef — through proximity sensors and information networks. Human interaction could trigger breathing, caressing, and swallowing motions. The structure also approximated the conditions of a lymphatic system, gathering toxins from the surrounding environment and converting them into harmless substances through filtering membranes and networks of tubing and vials of minerals and oils.

Hylozoic Ground (2010), a structure that “filters moisture and organic particles from the air,” by Philip Beesley. Photo copyright Pierre Charron.

This project displaced the notion of architecture as a protective shell, presenting an amorphous, atmospheric, biological enclosure that accommodates both human and environmental subjects. Posthumanist scholar Cary Wolfe explains that the installation’s informational network denaturalized the concept of life itself, pushing two opposite notions toward one another: it expanded the definition of “subjectivity” toward new forms of embodiment; and directed notions of codes, programs, and systems from the domain of the machine toward that of the human. This confronts us with the question of what is living and what is not.

The challenges of environmental and socio-technical change, emphasized by the Covid-19 crisis, prompt new ways of thinking about the state of our species. Continued and looming environmental catastrophe incites further exploration of the possibilities of architecture, acknowledging our codependencies with nonhuman entities in our surrounding environments. As with all tools and technologies, architecture can be seen in terms of its prosthetic relationship with the human body, as a means of augmenting our bodies’ capacities. With this comes the possibility for a greater degree of hybridization and interaction between the body and building.

Posthuman architecture could thus be regarded as a call to action: to survive the enduring threats of anthropogenic turmoil, we must eradicate the binaric notions of self versus non-self, and acknowledge the human body as part of a wider, hybridized network of human and nonhuman entities.