The conventional wisdom about networks suggests that their politics can be reduced to how centralized they are: A centralized network is designed for control, while a decentralized or distributed network is democratic. Early champions of the internet assumed both that its structure made it decentralized and that its decentralization would protect it from monopolization. In 1999, Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, wrote that the internet “is so huge that there’s no way any one company can dominate it.”

From the beginning, then, there was clearly a misunderstanding of what the internet was: Its biggest advocates believed it would be immune from corporate or state capture while empowering individuals with new tools for information sharing and production. But that view was always clouded by libertarian idealism. As Joanne McNeil writes in Lurking, “the internet I felt momentarily nostalgic for” — one where people came together in chat rooms and on forums to have discussions untainted by politics, social divides, or economic pressures — “is an internet that never actually existed.”

While it’s technically true that no one company dominates the internet today, the cloud services, undersea cables, and other infrastructures that power it are increasingly concentrated in a small group of telecommunications conglomerates and the owners of the web’s dominant platforms: Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Facebook. But looking back at the internet of the 1990s, the power of private companies was already apparent. Even though the internet’s infrastructure wasn’t fully privatized until 1995, online interactions were already being shaped by commercial pressures. In 1994, Carmen Hermosillo published an influential essay on the nature of community online, arguing that “many cyber-communities are businesses that rely upon the commodification of human interaction.” Hermosillo explained that even though “some people write about cyberspace as though it were a ’60s utopia,” early networked services — America Online, Prodigy, CompuServe, and even the Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link (the WELL) — were businesses that turned the actions of their users into products, shaped users’ interactions to serve corporate ends through censorship and editorial discretion, and maintained a permanent record that made cyberspace “an increasingly efficient tool of surveillance.” Counter to the boosterism of Wired, the electronic community, Hermosillo argued, benefited from a “trend towards dehumanization in our society: It wants to commodify human interaction, enjoy the spectacle regardless of the human cost.”

But looking back at the internet of the 1990s, the power of private companies was already apparent

Hermosillo was not the only voice pushing back against the libertarian framing of cyberspace. In 1996, technology historian Jennifer S. Light compared the talk of “cyberoptimists” about virtual communities to city planners’ earlier optimistic predictions about shopping malls. As the automobile colonized U.S. cities in the 1950s, planners promised that malls would be enclosed public spaces to replace Main Streets. But as Light pointed out, the transition to suburban malls brought new inequities of access and limited the space’s functions to those that served commercial interests. The same went for virtual communities where, under private ownership, “these agora function only in their commercial sense; the sense of the market space as site for civic life is subject to strict controls.” Commercial “communities” prioritized business interests over facilitating the participation of marginalized voices, promoting education and productive exchanges, and facilitating the democratic governance of digital spaces.

Light provided the example of Prodigy, which she described as an “electronic panopticon” that monitored public posts, censored those that were not family-friendly, and subjected users to “constant advertising” tailored to information collected about them. These same problems, of course, still characterize commercial communication platforms. If anything, the post dot-com-bubble approach to monetizing the web made it worse. “Web 2.0,” which Tim O’Reilly aptly described in 2005 as the effective platformization of the web, began a concerted effort to enclose all forms of online interaction so that everything users did could be captured and catalogued for corporate gain.

In less than 20 years, a small number of companies came to oversee many of our online interactions and dictate their shape to serve their interests, just as Light warned. As Twitter user @tveastman joked in 2018, “I’m old enough to remember when the Internet wasn’t a group of five websites, each consisting of screenshots of text from the other four.”

Yet in recent years, we have begun to see cracks in the model that allowed these companies to dominate: Digital advertising, which has been key to subsidizing the sites, services, and platforms that brought users on, is under threat. Part of this is because of increased efforts to impede the industry’s surveillance of users: Apple recently rolled out features to block ad targeting on iOS devices, which Facebook in particular saw as a huge threat. But digital advertising’s effectiveness in general is also being questioned. “Ad fraud,” or the misrepresentation of attention metrics (often through the use of bots), is believed to be rampant, and companies like Procter & Gamble and Uber cut their ad spend by $100 million each with little apparent impact on their revenue growth.

The vulnerability of the digital advertising model offers an opportunity to imagine a different kind of network, rooted in an alternative political agenda; one that elevates social benefit over corporate profit. But that won’t happen automatically. Without coordinated action for a better internet, the move away from digital advertising may simply lead to a further monetization of our networked interactions. The so-called creator economy is helping normalize a renewed emphasis on micropayments and subscription models, and the dominant social media platforms have followed suit with new monetization features, such as Twitter’s Super Follows and Facebook’s Bulletin. Beyond new apps and services, there’s a growing effort to graft an infrastructure of monetization onto the internet itself: Web3, a vision that Drew Austin describes as “a blockchain-based internet that works less like an open network circulating ‘free information’ and more like an expansive matrix of built-in ownership and payment infrastructure.”

On the creator side, these technologies offer what amounts to false promises to people who don’t already have a large audience. The creator economy is even more unequal for artists and performers because of how platforms drive a superstar economy that hollows out the “middle class” of professions. A small number of people with huge followings can leverage the new tools to generate more revenue, while a vast pool is left playing the virality lottery. Meanwhile, monetization features render the internet more unequal generally, linking access to an individual’s ability to pay and universalizing an invasive form of personal commodification where we are all incentivized to turn ourselves into products.

The vulnerability of the digital advertising model offers an opportunity to imagine a different kind of network that elevates social benefit over corporate profit. But that won’t happen automatically

But in some circles, there is hope that Web3 will renew the lost promise of decentralization of the early internet. Crypto enthusiasts and some activists in the digital rights space assert that cryptocurrencies, blockchains, smart contracts, and related technologies will evade the regulatory power of the state and allow people to avoid predatory intermediaries like major banks. Yet they downplay how centralized these technologies have already become and fail to explain how renewed libertarian appeals to decentralization will avoid succumbing to a similar corporate capture as the internet.

Web3 is a technological solution that does not contend with how power is distributed in the real world. It does not aim to produce a more equitable means of networking society; rather, it seeks to forestall the political struggles that pursuing that aim would actually require. Like other “decentralized” concepts, it is readily available for co-optation. Silicon Valley billionaires are already openly hailing cryptocurrency as a right-wing technology, while Amazon recently launched its own “distributed” network consisting of its own products. Bitcoin’s infrastructure is controlled by just a few major companies, and in the same way that Google financialized digital ad markets, Web3 seeks to extend the logic of financialization to even more of our digital interactions.

Appeals to decentralization too often fail to contend with the power structures that can take hold of supposedly liberatory projects. In an essay in Your Computer Is on Fire, Benjamin Peters argues that “networks do not resemble their designs so much as they take after the organizational collaborations and vices that tried to build them.” In other words, focusing solely on network design misses the political ideals and institutional practices that gave birth to them and that have been baked into them. For example, while anyone can still hook up their own server to the internet, the infrastructure is increasingly controlled by the same tech giants that have enclosed our activity on the network and whose devices we use to access it. Not to mention that purported decentralization did not stop mass surveillance by the National Security Agency or companies like Google and Facebook tracking virtually everything we do online.

Decentralization is not a politics in and of itself. Without a politics that explicitly seeks to serve the public while challenging corporate power, decentralization isn’t an actual strategy to decommodify our online interactions and reorient our networks toward alternative purposes.

The libertarian boosters of the early web held up the individual hacker as key to challenging state power and bringing about the liberatory potential of the internet, even as corporate giants took it over. Today, we hear about the individual creator, taking advantage of the opportunities offered by the consolidated internet, even as such narratives serve to keep us all creating content for platform companies to monetize for themselves. But individual actions will never generate emancipatory online spaces. That will require state action to fund and build the alternatives, pushed by an organized public demanding technology for the people.

There is an alternative to fetishizing decentralization. The history of state-driven communications projects in the 20th century offers examples of how to approach networks in different ways and with different politics.

When the history of the internet is usually told, it begins in 1969 with the first computers connected to ARPANET — an early packet-switching network funded by the U.S. Department of Defense that linked university research centers. But as Peters describes in How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet, the first proposal for a national civilian computer network originated in the Soviet Union in 1959, when Soviet cybernetics pioneer Anatoly Kitov proposed the Economic Automated Management System to help coordinate the planned economy. The network would have had a hierarchical design, but Kitov also built in the ability for workers to provide feedback and criticism, thus giving them greater influence over the planning process. The project was stifled by Soviet bureaucracy, but had Kitov’s vision been realized, worker participation would have made for a very different beginning to the civilian network era, orienting it around economic planning rather than knowledge transfer among academics.

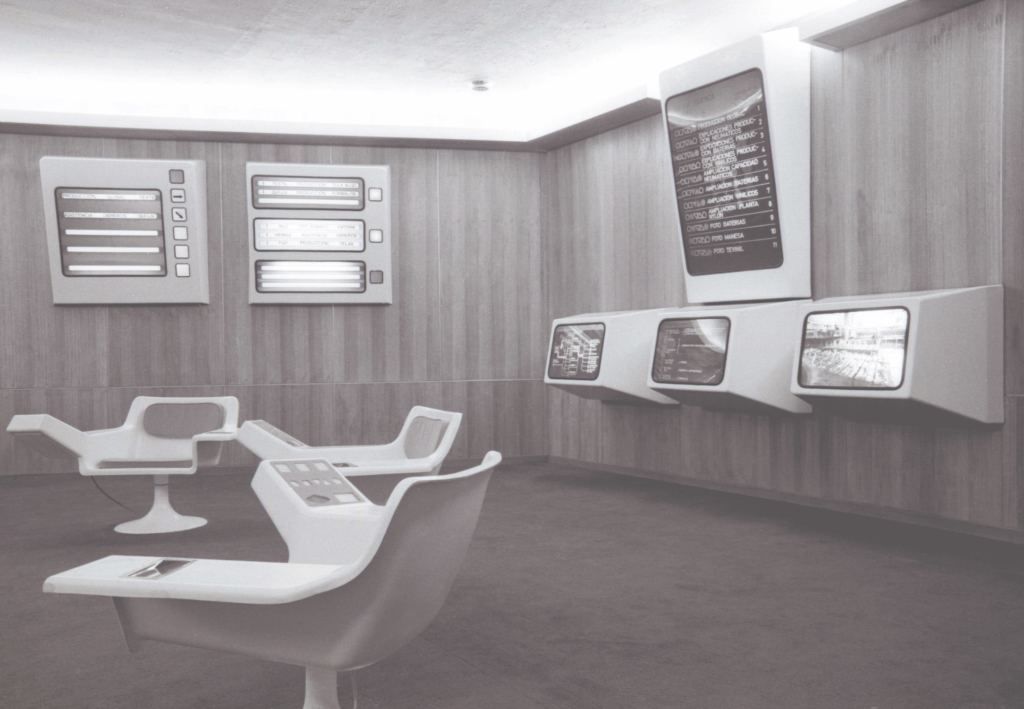

Chile’s Project Cybersyn, developed under socialist president Salvador Allende, had a similar economic orientation, but took a different approach. As Eden Medina explains in Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende’s Chile, it was an explicit attempt to break away from the “technological colonialism” of powerful countries like the U.S. “that forced Chileans to use technologies that suited the needs and resources of the wealthy nations while preventing alternative, local forms of knowledge and material life to flourish.” Its developers sought to imbue it with the politics of the left-wing government by seeking worker feedback, maintaining factory autonomy, and building a command center accessible to people without technical skills. The government hoped to use the network to coordinate production as it nationalized key industries, but we’ll never know how it would have operated in practice because Allende was overthrown in a CIA-backed coup in 1973. Medina asserts that the project demonstrated how rather than networks having an intrinsic politics, the political process itself can direct the design of networks, and innovation can occur outside the purview of market competition.

Another alternative was the Minitel system, developed in France after French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing declared in 1974 that “for France, the American domination of telecommunications and computers is a threat to its independence.” As Julien Mailland and Kevin Driscoll detail in Minitel: Welcome to the Internet, the system, which was rolled out in the 1980s, had a “hybrid network design, part centralized and closed, part decentralized and open.” While the state telephone company controlled the center of the network, the edges — the servers on which private services were stored — were managed by private companies. It also had monetization built into its design. When a user connected to a service — users could access news, games, sports updates, topical message boards, and much more — they were charged for every minute of access, creating a revenue stream for the service provider and the telephone company, which took a cut. This business model incentivized companies to keep people on their services as long as possible without having to turn to advertising or tracking. In fact, Minitel had a certain privacy built in; when a user’s bill arrived, it would not identify which services had been used.

Crypto enthusiasts downplay how centralized these technologies have already become. Decentralization isn’t a strategy to decommodify our online interactions and reorient our networks

Mailland and Driscoll compare Minitel to Apple’s App Store, where a centralized authority manages the “platform” and maintains standards. But unlike on Minitel, where decisions “were subject to due process and could be appealed in a court of law, Apple exercises absolute control over the communication that takes place on its platform. The public has no interest, no representation, and no recourse to settle disputes.” In other words, because Minitel was run by the state telephone company, there was public accountability both through legislation that granted citizens those rights, as well as through the representative democratic system.

These earlier network projects — especially Project Cybersyn and Minitel — were explicit efforts to block technological imperialism. The globalization of the internet in the years since has hampered such aspirations. Most governments can only speculate about networks with a different politics because the global networks their citizens already use appear to be beyond the regulation of any nation outside the United States.

The most notable exception is China, where the “Great Firewall” is at work. This set of technologies and legislation is often framed solely as an attempt to limit the Chinese populace’s access to sensitive information or communication about controversial topics — which is undoubtedly true and a problem — but its economic implications are arguably more important. China’s protectionist measures, paired with generous state funding, have allowed it to develop a domestic tech industry that has grown to rival that of the U.S. — something other countries are seeking to emulate.

Researcher Juan Ortiz Freuler argues that if countries in the Global South continue to have the value they create extracted by U.S. companies, they will become more open to the Chinese model. This fuels concern about the internet breaking up along national borders — what’s called the “splinternet.” But Ortiz Freuler argues that the trend toward fragmentation is not only incipient but has already occurred — just along platform and not necessarily national lines. In enclosing online activity, companies like Google and Facebook limit the open transfer of data and interoperability of services to cement their dominance. The response to a “splinternet” is not to assure the internet’s supremacy but to explore alternatives — and the alternative politics that would underpin them.

Technology for the public good will most likely not emerge from either side of a technological cold war between the U.S. and China. With a nod to the 120 countries that rejected the choice between U.S. capitalism or Soviet communism during the 20th century’s Cold War, Ortiz Freuler calls for a digital non-aligned movement to build information systems “geared toward solving the big challenges we face as humans on this planet,” including the climate crisis and global inequality. Our social, environmental, and technological salvation, he argues, is not to be found in the Global North, whose cultures are “so intertwined with the rationalities that bred capitalism itself.” The Global South, however, has the imagination to create different systems, as it has “seen its own cultures shattered by colonialism, only to see the pieces of it repurposed into a new narrative, favorable to its new rulers.” That is not to place the responsibility for solving the problems created by the Global North on those it’s oppressed, but they will likely have a unique approach to ending the dominance of U.S. technology — and rejecting its replacement by Chinese tech. We might expand Ortiz Freuler’s call to include oppressed peoples in the Global North as well — those who are subject to the surveillance and control of technical systems that are constantly expanding to cover more areas of life.

As the Chinese example shows, allowing alternatives to thrive will likely require existing platforms to be neutered, whether by blocking them or pursuing policies to tear down their “walled gardens.” We should also recognize the importance of state control of infrastructure and how that allows public entities to shape network outcomes. There are many forms this experimentation could take, but one example could be found in Dan Hind’s proposal for a British Digital Cooperative, consisting of a communication platform free from advertising pressures and designed to promote socially beneficial forms of interaction, and community technology centers that educate locals and develop technologies to address their needs. But could we also imagine Chile, as it undertakes to rewrite its dictatorship-era constitution, rekindling the anti-imperial technological spirit of Project Cybersyn? Or Cuba learning from its biopharma success to reimagine how digital networks should serve a socialist society instead of succumbing to the hegemony of US tech giants? Or even Brazil, once again under the leadership of Lula da Silva, leading a coalition to build technologies that serve the Global South?

After commenting on how we’ve idealized the early web, McNeil writes that “when I think I feel nostalgic for the internet before social media consolidation, what I am actually experiencing is a longing for an internet that is better, for internet communities that haven’t come into being yet.” Clearly, this is not just about decentralization; it’s about thinking through the outcomes we want to see and building institutions — and only later technologies — in service of those political goals. Instead of hoping a particular network design will be immune from corporate control, we can build a better internet by first building the political power necessary to make it a reality.