Technology is often premised on the act of disappearing — on cutting out the middleman, the storefront, the physical transaction point. (Legal protection for workers, job security, and benefits also disappear into the void.) Now it’s possible to receive therapy without leaving your couch (iCouch.me), to visit a doctor sans the waiting room (there’s the house-call app Heal or online urgent care option PlushCare), and to order medical records without waiting on hold for 35 minutes (just choose between MotherKnows and Patients Know Best). When it comes to abortion, the dream of disappearance came well before the apps. Pre-Roe, it was assumed that with legalization, abortion would slip from the cultural battlefield and re-emerge, quietly, as the routine medical procedure it is.

The pro-choice movement has long rallied around the mantra of “Safe, Affordable, and Rare.” Two-thirds of those mandates have been achieved, just not the way they were envisioned. The procedure is extremely safe, and also rare — or rarely accessible to most Americans, who often have to travel hundreds of miles just to get to a clinic. Affordability remains a huge barrier: With so few clinics, what could be a 10-minute procedure has morphed into a whole-day affair that often requires a full day off work. A 2014 study found that cost and travel were the top factors preventing earlier abortions.

Clinics are vulnerable for their separateness, which reinforces the idea of abortion as separate from ordinary reproductive care

In the immediate aftermath, many misread Roe as an endpoint, rather than an important victory in what now seems to be an endless war. “We thought we’d won. We thought it was over,” an abortion provider practicing since 1973 once explained to me. (He’s still providing.) Today, the frontlines of anti-abortion offensives are decidedly low-tech, and defense is often mounted in kind.

The clinic — the structure itself, beyond the medical technologies used therein — has become the most contested physical space in the seemingly endless battle over reproductive care. Just after legalization, hospital officials — who had once refused to sanction abortions, claiming that their hands were tied by abortion’s murky legal status — suddenly insisted that a deluge of patients seeking abortions would be too much to handle. Many doctors were hostile to abortion and didn’t want to provide them anyway. Swiftly, free-standing clinics were proposed as an alternative. Just after Roe, half of abortions took place in hospitals; by the late ’80s, 86 percent were happening in clinics, according to Eyal Press, who wrote a book on the subject. These days, most hospitals do less than 30 abortions per year.

Freestanding clinics offered a space staffed by supportive providers, where the cost of abortion could be kept lower than in the hospital. But these safe spaces soon found themselves under fire from state regulations, lack of funding, and violence. Clinics were more vulnerable for their separateness, which also reinforced the idea of abortion as separate from ordinary reproductive health care. In a hospital, at least, it would be harder for protesters to pinpoint providers and patients.

Most protesters today counter the free-standing clinic with their own physical presence, often crying “free speech” when providers complain about interrupted service. Their methods are usually quite low-tech — for instance, presenting poorly designed posters reminiscent of sixth-grade science fairs, demonstrating a similarly simplistic understanding of the science at play. More extreme measures are similarly basic, requiring guns, blocked numbers with which to generate bomb threats, and imitation (as in fake clinics masquerading as medical centers).

Upon arriving at a clinic, individuals seeking abortions are greeted by screaming, frothing protesters who dart around on motorized scooters, block cars, climb atop ladders with megaphones, pretend to be clinic escorts, and just generally stress out patients before a procedure that’s improved when said patients feel relaxed. For her book Contested Spaces: Abortion Clinics, Women’s Shelters and Hospitals: Politicizing the Female Body, architect Lori A. Brown interviewed a number of clinic employees. One clinic manager explained she has “no problem with them protesting, but what they’re doing is crazy … even when we prepare the patients, even when we let them know what’s going on, until you see it, until you’re in it, you can’t understand it.”

Anti-choice extremism grew through the ’80s and reached a peak in the ’90s, with clinic bombings, arson attacks, kidnappings, and murders. “Today, it seems that there’s a little less violence because the right wing has been able to make a lot of legislative changes,” an abortion provider told me in 2015. “The frustration and the desperation they felt in the first 20 or so years has been mollified by their ability to generate meaningful legislation for their side,” including significant state and federal advancements, plus some key Supreme Court decisions.

The Supreme Court has ruled in favor of small floating buffer zones that move with the individual entering a clinic, and against larger static buffer zones. In the 2014 McCullen v. Coakley ruling, the Court held that a 35-foot buffer zone Massachusetts had enacted deprived protesters and petitioners “of their two primary methods of communicating with arriving patients: close, personal conversations and distribution of literature. Those forms of expression have historically been closely associated with the transmission of ideas.”

Speech on sidewalks around abortion clinics is protected by the constitution, but blocking entrances isn’t. The ruling left some discretion to states, specifically with regard to “narrower” laws: A state, for example, can pass a law allowing police officers to force an aisle between protestors so that patients and doctors can get through. But without constant police monitoring, protestors often block entrances and simply move if and when a cop car rolls up.

Landscape work is scheduled to coincide with protests, drowning out chants covering protestors in mulch

Even though they’re able, most states seem reluctant to enact either federal or state protections for clinics. Over three decades later, only three states have enacted versions of the 1994 Federal “Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act,” which specifically makes property damage and intimidation or interference at a health clinic illegal. Just 11 states have passed legislation making it illegal to obstruct a clinic entrance, and a measly six have laws on the books about threatening a clinic staff member or patient.

Since the low-tech tactics of protesters are so hard to counter through legal avenues, American clinics have to rely on low-tech defenses. Shatterproof glass, metal detectors, and security guards are common. When repeated requests for police intervention go unanswered, clinics deal with noise violations by playing classical music loudly to counter the protests or moving procedures to the back of the building to reduce patients’ exposure to the sound.

Facing political hostility and police apathy, clinics often respond to protesters on their own, with creativity borne of shoestring budgets and architectural impediments. In her book, Brown details how one clinic fought protestors by vying for the area’s weekly noise permit. Both the protestors and the clinic would request it every week, but whoever’s email got in first would be awarded the permit. If the protesters got it, they could use a microphone; if the clinic got it, they didn’t do anything beyond preventing the protesters from having it.

When protesters came with signs, one clinic responded by hanging a 1-800-ABORTION sign in view so any media coverage came with free promotion. Another pretty effective tool is lawn care: remote activated sprinklers soak protesters, so landscape work is scheduled to coincide with protests, drowning out chants and giving protestors a choice between getting covered in mulch or going away. One clinic put up a rather effective hedge until police determined it’d be a perfect place for anti-choice protestors to hide a bomb.

Targeted Regulation of Abortion Provider (TRAP) laws are forcing clinic closures around the country and, given that 75 percent of American women getting abortions are low income, it makes sense to focus on making (already safe) abortions as accessible and cheap as possible. Medical abortions, a series of pills swallowed to induce miscarriage in early pregnancy, once seemed like an effective alternative to clinic visits. A number of studies have suggested that individuals are more than capable of doing it all at home, dealing with side effects, and seeking medical attention in the case of any complications.

Data from a large clinical trial of Mifepristone–Misoprostol abortions across the U.S., involving 2,121 women aged 18 to 45, “suggests that most women can handle most steps of the medical abortion process themselves, effectively and safely.” The authors also noted that the “utility of clinic visits to ingest mifepristone and misoprostol is questionable,” arguing that “even the follow-up visit could perhaps be replaced by telephone follow-up combined with home pregnancy tests” and suggesting that “alternatives to the present protocol might allow greater control, comfort, and convenience at lower cost.” Two-thirds of abortions happen before eight weeks, but if an abortion pill were effective up to 12 weeks instead of 10, 89 percent of those seeking abortion could theoretically take a pill or two to end a pregnancy.

But since it was introduced in 2000, mifepristone, the first half of a medical abortion, has been under the FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS), which limits distribution methods, and is used mainly on drugs with a limited track record, or those with a serious risk for abuse or complications. A scathing commentary just published by a number of health experts in the New England Journal of Medicine accused the FDA of over-regulating mifepristone: “It’s unconscionable that the REMS restrictions remain after 16 years of data showing mifepristone is an exceedingly safe and effective abortion method,” said Beverly Winikoff, President of Gynuity Health Projects, in a statement.

Assuming that advancing technologies can replace the physical space that’s guaranteed abortions for decades is high-risk

Pharmacies are generally located in much smaller towns than hospitals or clinics, and are more accessible to a larger population; the possibility of a prescribed or over-the-counter medical abortion is incredibly promising, but fraught with risk. Even if FDA regulations were to be lifted, it wouldn’t necessarily mean that individual pharmacies would choose to stock (or dispense) the pills. Already, the ease of obtaining emergency contraception — which, for the 100th time, isn’t an abortion — varies dramatically. In 2007, Brown surveyed pharmacies around the country, calling and asking “Do you sell emergency contraception? Can I fill my prescription?” Many pharmacists said yes, but many did not. Kentucky pharmacists said things like “we sure don’t” and “there’s not a pharmacist here that will sell it.” In Mississippi, it was “I don’t know what that is” and “we stock but I won’t dispense it.” In North Dakota it was “looks like I’m out,” while in Utah a simple “nah” was offered. Now imagine asking, “Do you sell medical abortions?”

Shifting medical abortions from a clinic to a pharmacy may decrease distance, but make access nearly impossible, as another simple intervention faces an equally simple barrier. Unfortunately, it’s a problem with less clear counter actions. Exploring possibilities for similar situations, the Dutch non-profit Women on Waves flew their first abortion drone across a small river between abortion-friendly Germany to abortion-hostile Poland in 2015. There’s even a video of the drone’s journey on YouTube, but it’s pretty anti-climatic and ends with a nose-dive in the grass. When the drone was face down, two women swallowed the pills. German police on the other side of the river confiscated the remote, and charges over improper distribution of medicine were filed before eventually being dropped. Women on Waves has docked in countries hostile to reproductive rights and taken patients out to international waters to provide abortions, but it’s less of a large-scale solution, and more of a publicity-based challenge to egregious reproductive rights violations.

In the United States, activism surrounding medical abortions has largely focused on wrestling it out of REMS status; if and when that occurs, limited availability will present the next challenge. Making abortion more available at home is a necessary and laudable goal, but assuming that advancing technologies can replace the physical space that’s guaranteed abortions for decades is high-risk. Though clinics have been subject to an immense amount of devastating and sometimes deadly violence, they remain one of the few safe spaces for individuals seeking reproductive care.

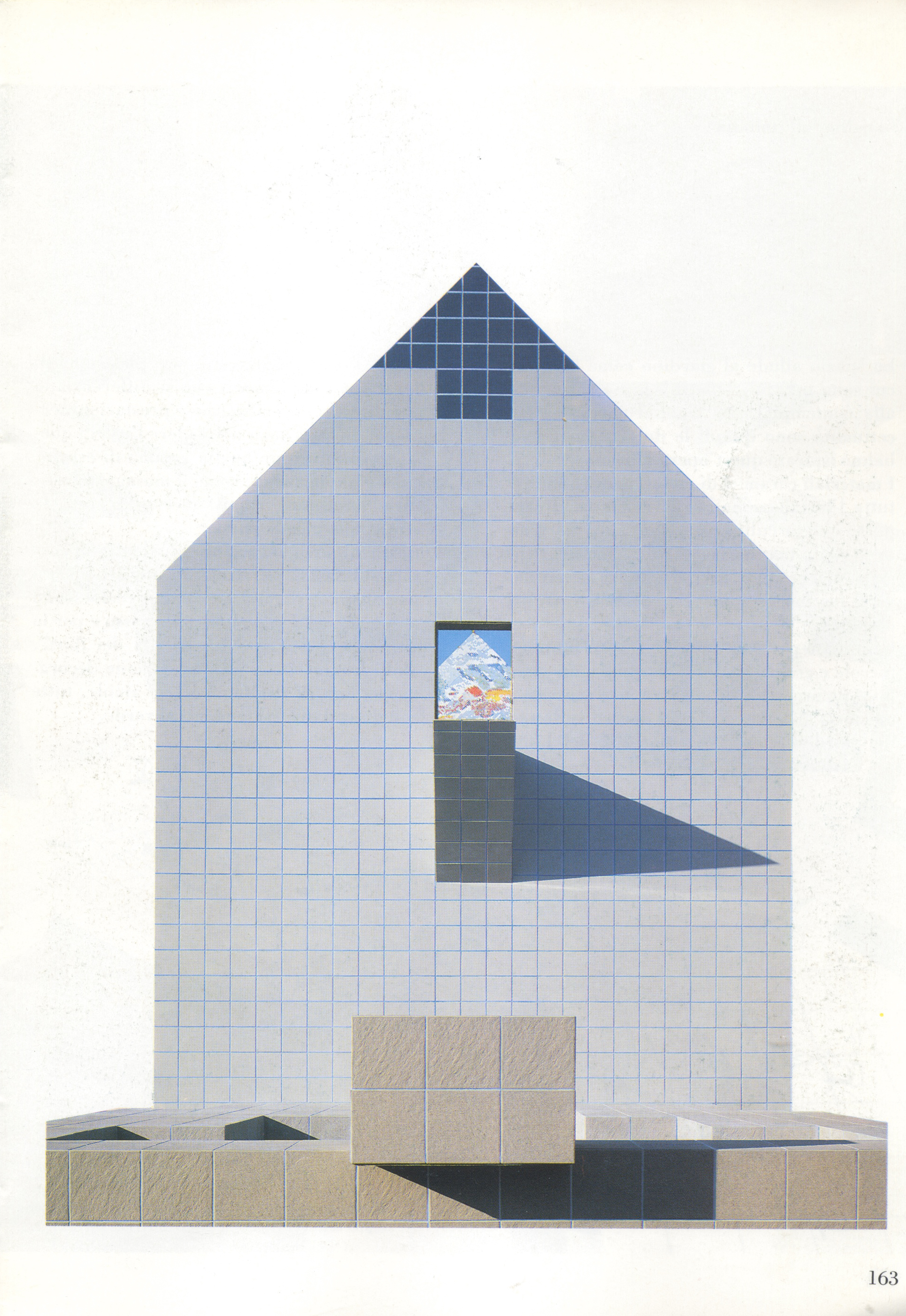

One of the most effective approaches to ensuring safe, accessible abortion, then, might not be to look to new technologies, but to continue strengthening the one that has proved most reliable thus far. Making abortion accessible isn’t just about literal access, but also providing a safe and welcoming environment, which continues to establish abortion as the routine procedure it is at a time when 55 percent of med schools don’t offer students clinic exposure to abortion and only four percent of U.S. hospitals provide abortions. A few architects around the country are working to enhance clinic design. “Our strategy took a unified approach to opposing goals: to increase security against terrorist threats and to express warmth and welcome to [Planned Parenthood] staff and patients,” architect Anne Fougeron’s site explains. (Brown does clinic re-design, too.)

In Fougeron’s clinic design, frosted glass walls balance openness with privacy needs; integrated bullet-resistant desks provide safety without being too visually obtrusive; and bright color paint counters the idea that these medical centers need be drab. One Oakland clinic has a special waiting area for children to play in, the most honest response I’ve seen to the fact that 59 percent of those getting abortions are already mothers. Skylights, canted walls, and courtyards bring natural light into the other Oakland clinic her team worked on. “This colored refracted light, which changes in hue and intensity throughout the day, is a constant reminder of the exterior world beyond,” the architects write. Sometimes it’s the clinic itself that provides a necessary escape from that exterior world beyond.

When I worked as an abortion doula, one thing that surprised me was that most patients I saw didn’t consider their abortions to be remotely political. Before that, my only exposure to abortion had been to the activism surrounding it. Still, giving patients the chance to quietly be together before and after a procedure that many of them faced alone was paramount, no matter how they conceived of it.

The recovery room, which I dipped in and out of on each side of an abortion, offered patients a sense of community they seemed to appreciate, even when most were eager to get home. Those who cried in pain found another face stained by tears, those who struggled with guilt could see another patient who considered things differently and was cracking up over the cheesy movie that played on loop. The recovery room doesn’t host consciousness raising circles, just space for a number of patients who’d otherwise never meet, sitting in lounge chairs, sipping juice, and sharing an experience.