“A photograph is incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened. The picture may distort; but there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist, which is like what’s in the picture,” Susan Sontag writes in On Photography. The “what are you wearing today” (WAYWT) thread — now staple of fashion forums online, especially menswear forums — wants you to provide evidence. There are no other ways to answer the question without resorting to posting a photo of your outfit, or “posting a fit.”

WAYWT is still “WAYWT” on Reddit’s MaleFashionAdvice subreddit. It’s also “WDYWT,” or what did you wear today on 4chan’s fashion board, /fa/. On Reddit’s MaleFashion subreddit, I find “WIWT,” what I wore today; “WIWY,” what I wore yesterday; and “WIW,” what I wore. Members of communities like these seem to gravitate toward these spaces after a sudden urge to dress better overcomes them elsewhere on the site, in their early 20s or mid to late teens. Many learn how to dress on the internet now, and the trends, images, and conventions produced by their efforts bear the imprint of online dynamics.

Like photos in general, looking at a “fit pic” is not analogous to experiencing clothing in person. In real time, outfits are noticed, witnessed, spotted in motion; they are incidental to existing in public space. Bodies are attached to faces; brand names might be visible, but are sometimes deliberately left hidden, or implied. In public space, contexts shift and interlock: We are mindful of dressing for occasions — on the subway car, you can guess who’s on their way to class and who’s on their way to a job interview or the gym. Style is both a strength and a vulnerability. When you leave the house, you have no choice but to be seen; getting dressed is a way of making a pitch for yourself.

The contextual cues that we use to evaluate an outfit in real time are dynamic in public. But on these forums, a good picture of an outfit is a good outfit

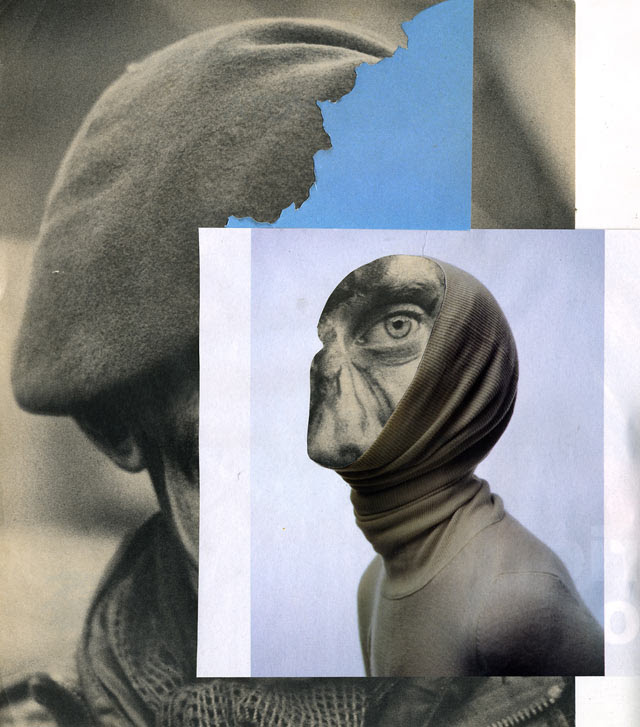

By contrast, participation in WAYWT and its variants is voluntary, and necessitates deliberation: WAYWT isolates the unconscious act of noticing, witnessing, or spotting and converts it into something more intentional. The average of every “fit pic” is a careful photo of a man, face cropped out or scribbled over or carefully blurred. (Women participate in these communities as well, despite the menswear focus.) The image is typically more coherent than striking; it always makes sense to look at. Outfits are positioned in the most neutral corners of posters’ bedrooms or living rooms, or the spaces that match them the best; mirrors that reveal little reflected behind them. The brands present are neatly listed nearby, in the body of an image board or forum post, in the titles or comments of posts on Reddit.

The internet inverts geography and physical presence — it provides a collective space for disparate environments — and style is influenced by both. Fashion forums on the internet have developed a grammar that seems to understand this. Outfits are immediate and scrollable, elements easiest to assess within the confines of one’s browser. A picture has to look good against the web page it’s hosted on, before anything else — a good outfit alone is insufficient, even impossible, without a matching backdrop. The contextual cues that we use to evaluate an outfit in real time, which lead inevitably to some assessment of the person wearing it, are dynamic in public: an outfit assembled for a party is still worn on the subway, on the sidewalk. We have limited control over the backdrop that frames us, or the people on whom we might make an impression. A good outfit accounts for these variables. On these forums, the context is static: a good picture of an outfit is a good outfit. Users feel compelled to note when they are being “lazy,” or when they know that they are wearing something “basic” or “boring,” or when they are “trying something new.” They might explain where they wore an outfit; the event they might have worn it to. And a good outfit has less to do with the synergy between the wearer and their clothing than between the clothing and the backdrop, as well as the meta-backdrop — the confines of the threads these images exist in.

Good in these spaces is often represented by the quietly neutral, potentially even aloof. Guys eternally still or mid-stride against nondescript walls in photos that sit nicely against the endless clean of minimalist UI. Hidden faces mean you focus on the clothing, outfits disembodied, and some level of anonymity is allowed to be preserved — a photo of yourself with no face provides a clear limit to strangers’ critiques and presumptions. While participation is necessarily social and never not intentional, it is frustratingly impersonal for that reason. The fashion internet’s canon reflects the folded space it occupies more than anything.

Spaces like 4chan’s /fa/ are not only focused on fashionable clothing, but also fashionable lifestyles, or the appearance of them. The board is full of threads dedicated to establishing and building on their own aesthetics, and the advice offered is inclined toward fitting those conventions. The r/MaleFashion and r/streetwear subreddits are dotted with Imgur links to “inspo” albums; /fa/ houses a myriad of threads that classify, seek to classify, and provide inspiration for endless looks, along with questions about what is “/fa/” and what’s not — its definition is never fixed, entirely dependent on the opinions of strangers, and meant to look like the opposite: intuitive, immutable.

The posters in these threads are drawn to a specific aura, not a mere costume. The meaning is in making the identification, creating the category

Many posters on /fa/ are preoccupied with “–waves” and “–cores,” aesthetics built upon photographs with only remnants of their contexts — “terrorwave,” for example, which was founded on well-composed, entrancing photographs of Afghan fighters and soldiers in Eastern Europe, but only entailing utilitarian clothing, Adidas sneakers, and low-key military surplus wear in neutral tones. Carefully constructed movie stills can go into inspo threads — images of Ryan Gosling in The Place Beyond the Pines, candid photos of soldiers looking gritty and careless can go into inspo threads, the fervor of the gunman that assassinated Andrei Karlov can go into inspo threads, all of them qualifying for different “–cores” and “–waves” with every repost. Personal style is subordinate to these “waves,” which become recognizable through participation — filed into inspo albums, easily reblogged on Tumblr, “liked” on Instagram, infinitely sortable.

While anybody can bleach their hair and wear white T-shirts, or buy vintage military uniforms, or wear a suit, the posters in these threads are drawn to a specific aura, not a mere costume. They seem to need genres in order to make sense of things — a single photo allows one to ask “what core is this,” based on purely visual understandings, subsuming individual narrative into that of the thread itself. The meaning is in making the identification, creating the category.

The desire to be cool seems incompatible with the compulsive tendency to materialize a presence on the internet, and to sift anxiously through the presences of others. The passion for collection mediates no matter what, as long as one can suggest an underlying sort of critical-ironic distance, as demonstrated by the “starter pack” meme, a cousin of “get the look” packages in fashion magazines: a grid layout of the various components of a subculture, indexing uniforms to incredibly specific points. These points become strange signifiers; an item of clothing reaches “meme” status based on its documentation on the internet, how it’s documented, and who documents it, not when it becomes “trendy” off-screen. Starter packs identify the shared affects and social behaviors of these subcultures with the same pattern-recognition sense that leads to the construction of that aesthetic in the first place. The more thoroughly mapped an “aesthetic” is, the more difficult it is to execute earnestly — take the memetic evolution of “clout goggles” as tied to Soundcloud rap, now saturated to the point that wearing them must somehow imply some sort of bitter irony. These “aesthetics” have less to do with things people actually wear on their body than the idea that they would. They’re lifestyle brands, constantly collated in the past tense — “starter packs” as systems of reference that expire as they emerge, newly invented “cores” and “waves” that track aspirations.

A now-dated pejorative expression in the vernacular of these forums is “dressed by the internet” — as in, the source of a look is too obvious, evoking the primordial sense that one might be “trying too hard.” But dressed for the internet might be more accurate. The looks themselves are born online, and subject to online conventions; the outfits are partly assembled to be seen online, adapted to the message board or timeline more than to public space, and are meant to be judged against it. “The internet” almost always implies distance; the ability to recognize what it looks like is a nervous reminder. “The internet,” even now, almost always implies a distance from “real life,” which might be more accurately described as “real time” — the immediacy of bodies in public space. Of course, the internet is real life, but it’s a domain of reality subject to its own logics, its own sets of norms, as well as its own accelerated pace: ideas of whole ways of being, arrived at collaboratively and then passively falling away.

This essay is part of a collection of essays on the theme of EXTREMELY ONLINE. Also from this week, Eric Thurm on galaxy-braining the galaxy brain meme.