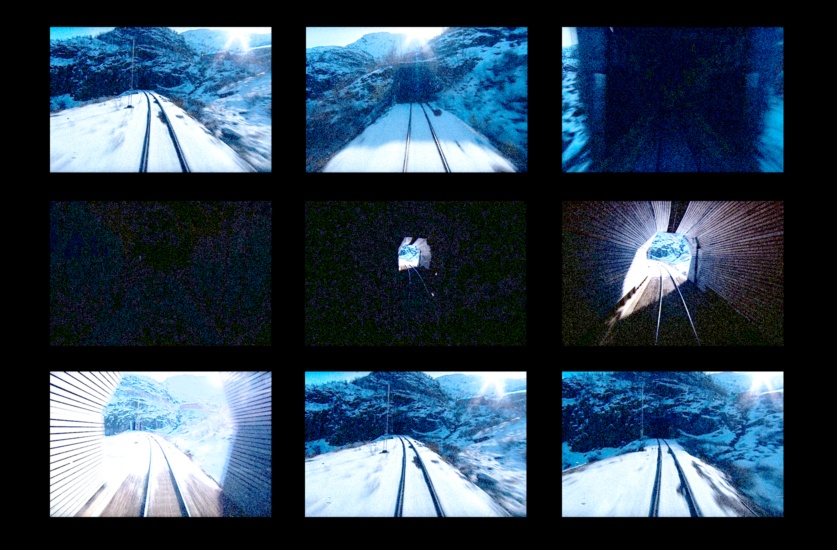

You hear a slow clicking, the course scrape of metal on metal, and a whirring sound as the train picks up in speed. To the right is a house-lined street; to the left, industrial buildings. Ahead are the tracks, distant mountains, and a clear blue sky. Slowly, you leave the city and enter lightly wooded plains. Four hours in, the landscape turns snowy, and tall evergreens line the tracks. You enter pitch-black tunnels and curve around mountain bends, passing through small towns along the way.

This is the 10-hour Norwegian train ride from Trondheim to Bodø in spring. On YouTube you can catch the same ride in winter, summer, or fall. Or if you’re into a more urban setting, you might take a similar ride around Chicago and its suburbs through a “real-time” video from the Chicago Transit Authority. But it’s not just train rides. YouTube offers countless videos of boat rides, aquariums, knitting marathons, babbling brooks, and more. Often referred to as “slow TV,” it offers an alternative to the dense narrative and complex plot lines of many scripted shows. With slow TV, the one definitive characteristic is that not much will happen.

With slow TV, the one definitive characteristic is that not much will happen

I came across these sorts of videos while studying for my PhD examinations. For six weeks I spent 10 hours a day in my office reading and taking copious notes, accompanied by the sights and sounds of train rides through Scandinavia. These offered just the right amount of presence without excessive distraction. When my eyes tired from reading, I glanced up at my screen and watched scenic landscapes pass by. It was not compelling enough to distract me; instead, it allowed me to regather focus to return to my books.

Slow TV resembles earlier experiments in minimalist film, like Andy Warhol’s Sleep (1963), which, as promised, depicted nothing other than a man sleeping for roughly five hours. But contemporary slow TV began when the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation’s aired uninterrupted footage of a seven-hour train ride from Bergen to Oslo, shot from the front of the train. Nearly a quarter of the population of Norway tuned in to at least some of the train ride. Since then, similar programming has become popular in Scandinavia and is catching on outside the region. In 2016, Netflix began streaming some of the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation’s slow TV programming, and Amazon has launched the Window Channel, which offers a “vicarious travel experience” with clips of scenery from around the world.

But YouTube is the central hub for finding slow TV videos, with playlists of hours and hours of serene visuals readily discoverable through straightforward searches. Whereas slow TV was once only available to viewers in the countries in which it was produced when broadcast networks decided to air it, YouTube allows audiences from all over the world to tune in at any time. This dynamic creates a surplus of formerly scarce video content, and that surplus opens up opportunities for new types of viewing experiences.

When visual content was scarce — when it was only available at certain times and through certain mediums — it generally had to be information rich, with compelling plots and characters that would draw in the viewer. But in a media environment where content is everywhere and readily available at any time and on any screen, low-information video like slow TV becomes an appealing contrast.

Minimalist videos like slow TV are neither hot nor cool, neither readerly nor writerly. They don’t require much of viewers, yet they also don’t prescribe a meaning

Comments on these videos exhibit the spectrum of viewers’ reactions: confusion, fascination, delight, boredom. Some report using the videos as sleep aids, for mindful meditation, or as a companion to household chores or office work. It can make a room feel as though it has come to life without requiring much in the way of viewer participation. They serve as a gentle background to activities that require a certain level of attention.

These minimalist videos and the ways that audiences use them complicate a McLuhanesque approach to theorizing audience participation. McLuhan divided media into two types — “hot” and “cool” media — according to the demands they make on viewers. Film and radio are, in his view, hot media: they are low-participation and don’t demand that viewers fill in any gaps or process the content to go along for the ride. Television and comics, by contrast, are cool media that demand audiences fill in more gaps to comprehend their meaning. Roland Barthes made a similar distinction between “readerly” or “writerly” texts. A readerly text has a clear narrative and characters with overt motivations, which allows readers to take a passive role; a writerly text requires active and continual deciphering.

Minimalist videos like slow TV are neither hot nor cool, neither readerly nor writerly. They don’t require much of viewers, yet they also don’t prescribe a meaning. The audience create its own: whether that be relaxation, hypnotic transfixion, “vicarious travel experience,” or simple background. They trouble the idea that there is a continuum from readerly to writerly, or from hot to cool. Instead, the intensity of attention operates independently of the project of making meaning. This highlights the broader point that media viewing is not simply a matter of either transmitting information or presenting a consumable narrative, but of creating a viewer experience on a deeper, more variable level.

What makes the minimalist video genre novel is how it blends the static contemplation that older art forms like painting invited with the movement afforded by electronic media. John Berger in Ways of Seeing made the point that a painting is primarily and essentially silent and still, but we may see that fact become more complicated with new genres like slow TV. These videos are updated versions of framed photos — a landscape that comes to life and serves the individual needs of viewers. Slow TV is not simply an alternative to the fast pace of modern life but a new mode of engagement with media that transcends arbitrary binaries like education or entertainment, or engaging or disengaging, offering something altogether different. It is not, in the mode of a film or television show, a world into which we can escape but an ever-present companion to the mundanities of everyday life.