Watching YouTube, I wonder if Grammarly’s “Write the Future” ad campaign is targeting me. Marketing itself as a writing application and grammar checker, Grammarly — like other proofreading services like Hemingway and Ginger — purportedly offers a vital supplement for digital composition by providing grammatical and syntactical advice in real time. Maybe routine searches for syllabi and novel summaries leave me algorithmically predisposed for these EdTech advertisements — the network is talking back to me. In this way, I found myself simultaneously sympathetic and unnerved by their “term paper” commercial, which stages the all too familiar anxieties many college students experience when writing academic papers.

The ad begins with a head-on shot of the writer’s face, contorted and confused by what Grammarly has marked “passive voice.” Cutting back from the laptop screen to the student’s face, we watch them rub their eyes in frustration. They’re sitting on a bed; the wall behind them is filled with books and lit by string lights; it’s clearly night. The camera returns to the computer screen as the student rewrites the sentence, “Words are often portrayed as if they are powerless,” beginning instead with “Our language often, ironically….” Grammarly and the student are in dialogue here, dialectically honing an essay titled, “Words: Humankind’s Most Powerful Tool.” Grammarly suggests that language is not merely a mediating tool, but a translation machine that can re-present the writer. By assembling the sentence in just the right way, by selecting the correct words, we can manifest our best selves.

While writing is supposed to intimately represent who we are, this software highlights the perpetual inadequacy of translation, intervening with standardization as optimization

In “A Cyborg Manifesto,” Donna Haraway wrote that “Writing is pre-eminently the technology of cyborgs, etched surfaces of the late 20th century. Cyborg politics is the struggle for language and the struggle against perfect communication, against the one code that translates all meaning perfectly.” For Haraway, language and writing are counter-political tools for disrupting the monolithic and oppressive codes of late capitalism and patriarchy. Grammarly, on the other hand, understands language as a privileged access point into these systems. Language becomes less a conduit for faithful translation than a tool that filters communication to fit the “one code” of neoliberalism — a cyborg politics predicated on assimilation rather than transformation; identity rather than difference; stabilized fluidity.

Proofreading software raises questions about the relationship between voice and writer by opening a yawning gap between their presumed unity. While we like to pretend that our writing can intimately represent who we are, this software highlights the perpetual inadequacy of translation, intervening by positing standardization as optimization. But how much of “me” does “my” writing ever actually reflect, let alone when it’s mediated through this technological prosthesis? The stakes of performativity aren’t merely elucidated here, but rather amplified by our relation to these emergent technologies. They provide another site for examining our interwoven anxieties about representation and identity, perhaps helping us ask a more existential question: Who do I become, and what do I relinquish, in the effort to account for myself?

Spelling and grammar standardization software renders effective communication and correct grammar coterminous, (re)producing a monolithic syntax by which all our expression is judged. How we articulate or perform ourselves online makes explicit the anxiety we experience IRL, attempting to present whatever “self” we imagine desirable. As Rob Horning argues, “With social media, the compelling opportunities for self-expression outstrip the supply of things we have to confidently say about ourselves.” Traversing a multitude of networks with varied social and linguistic expectations — email, Facebook, text, Twitter — amplifies the impetus for “appropriate,” site-specific communication. Software like Grammarly grounds us in a particular context by standardizing our performances, assuring us we can be rendered legible so long as we take a particular, circumscribed form.

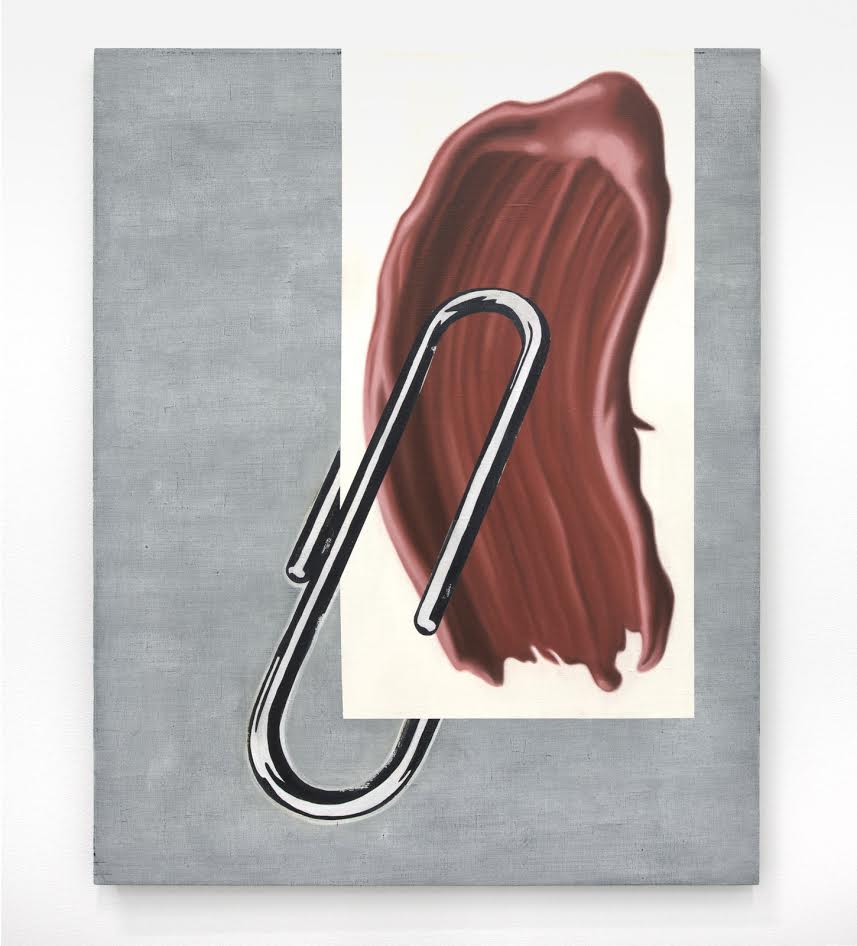

Writing apps are comparable to FaceApp, Facetune, Bestie, and other post-production beautification apps, which remind us of our inability to conform to specific socio-cultural standards. They teach us what is beautiful or desirable by continuously reminding us of how we are not, at least not without some kind of modification. This standardization leads to a paradoxical legibility and imperceptibility, allowing us to assimilate into an oversaturated network. Access requires acquiescence, a willingness to conform and contort ourselves into the requisite form. The danger of complying with these services and ideals is not merely inauthenticity, but the reduction of difference. Performativity and representation constitute a vicious feedback loop in which prescriptive standards circumscribe the possibilities of permissible expression.

While the enhancements offered by beautification apps are often read as disruptive — the overlay distorting or misrepresenting our faces — writing apps swerve this charge by erasing the distinction between original and augmented forgery. They collapse the perceived distinction between the “real,” material world and its overlaying data. By weaving post-production into production, the demarcation between writer and software, subject and object, “authentic” representation and inauthentic performance are rendered indistinct, reconfiguring our subjectivity in the process.

While the enhancements offered by beautification apps are often read as disruptive, writing apps swerve this charge by erasing the distinction between original and augmented forgery

If language is figured as the original prosthesis inaugurating humanity, proofreading technologies become disciplinary apparatuses modulating neoliberalism’s posthuman subject. These apps function less dictatorially than by subtle and insidious coercion, narrowing and replacing our language, allowing better integration into neoliberalism’s dreams of seamless flows of information and capital that language otherwise disrupts. These apps exemplify the imperative for subjects to take responsibility for their imbrication or extrication from the market driven social order. Of course, this supposed optimization is anything but lossless: Forced to internalize this grammar, we are reconfigured into a more recognizable form, de- and rematerialized for easy reproduction and consumption.

The process of writing is not privileged here, nor is the subject’s becoming; rather, what matters is the final draft, our “best self.” This stable version of an infinitely more complicated subject is easily circulated and commodified, but it is also infinitely reconfigurable. Writing becomes almost magical, or at least causal, with specific words, sentences, and syntactical variations producing desired effects. We are unmarred by the anxiety of communication when we realize we just need to give others the self they want.

At the end of “Term Paper,” the protagonist gives a confident nod when they see an A+ on their work, and the comment “Wonderful use of words,” written so legibly in red marker that one wonders if the commercial’s writers have ever seen a humanity professor’s handwriting. This is not merely the fantasy of the achieving student, but of the infinitely fungible subject, able to reconfigure their self to fit whatever situation may be at hand.

Grammar correction software reconfigures its users by offering prescribed and predetermined phrases, words, and syntax. These suggestions become integrated into our composing circuit, optimizing our prose while teaching us what we’ve long known: Writing doesn’t happen alone, but entails interacting with a variety of human and nonhuman others. The banality of our collaborative relationship to pen and paper, or keyboard and word processor, takes new shape with these new technological intermediaries, amplifying the (in)distinction between subject and object at constant work in reading and writing. Grammarly insists on the separation between subject and object and posits writing as representational, a stand-in for the writer rather than a deployment of force.

The process of writing is not privileged here; what matters is the final draft, our “best self.” When content is deemed unimportant, so is the writer

But language is a deployment of force. Content is never translated one-to-one, because meaning emerges from the dynamic relationality of reader and text, affecting and compelling the reader though never in predictable or stable ways. Form and content are interwoven, equally vital partners in the production of meaning, but writing apps like Grammarly confuse form for content. In the process, they sell the notion that form supersedes content, that content is hyper-fluid, easily reconfigured for seamless integration and compatibility with myriad contexts. When content is deemed unimportant, so is the writer these apps purport to help. Or rather, the writing subject becomes anyone, the faceless prosumer of neoliberalism.

As N. Katherine Hayles notes, “When bodies are constituted as information, they can be not only sold but fundamentally reconstituted in response to market pressure.” We become further imbricated in the flow of contemporary capitalism, ripped from our bodies, becoming no one. Who we are is less important than who we’re willing to become, so long as that new self remains fungible. It’s no coincidence that Grammarly’s other ads — a VP introducing himself to a new office, a furniture restorer composing the perfect ad — are geared towards economic transactions: handing in a paper, a new job, advertising a newly refinished table.

A friend recently bemoaned our high school and college education, noting that it didn’t adequately prepare him for his job as a management consultant at a large and well respected firm. “I honestly feel my high school and college education coming up short in many discussions (how to quickly structure sentences, grammar perfection at the 99.9th percentile, just small things like these),” he texted me. It was then that Grammarly came into focus as a prosthetic for softening entry into spaces we might otherwise be barred from, mitigating the differences made legible by our language. In this way, Grammarly becomes the reminder of all we relinquish in order to succeed, or all that we give up in service of becoming a productive but docile subject.