In China, Tencent’s “super-app” WeChat — an instant messenger with grafted-on social media, news, payment, and local services features — has grown to become a stand-in for the wider internet. Social and online life is unimaginable without it. Tencent calls it a “lifestyle app,” and for once this typically empty marketing speak has a ring of truth to it. WeChat is, as academic Yujie Chen put it, “super-sticky,” inseparable from everyday habits in Chinese society.

For many in urban China, WeChat has collapsed the personal, professional, and parasocial into one interface, and more crucially, one single online profile. Work, social life, shopping, payments, news — very little of daily life requires one to leave the WeChat interface. It isn’t much of a real option to leave either. Since the start of the pandemic, many city-specific Covid test-result dashboards and contact-tracing alerts are solely accessed within WeChat. It is a complete, and completely surveilled, lifelog.

As a necessary survival skill, WeChat users must develop a fluid understanding of the app’s meta-structures: the circles of visibility for posts, an awareness of the potential for incriminating screenshots, techniques for reading behavioral gestures via quirks of its interface. When everything is said on the record, there is a lot at stake in how you speak. The Chinese web is, above all, a linguistic battleground haunted by deletions, ringed with no-go zones, and pockmarked with banned phrases. WeChat frequently erupts in whack-a-mole skirmishes between users trying to push through a sensitive message, and censors (now both human and AI) zapping recognizable instances out of people’s timelines and chat logs.

Sticker pack: Little Blue’s Social Life

Being online means arming yourself with a sophisticated arsenal of forms of indirect speech: The widespread spiky, passive-aggressive performativity seen on the platform, for instance, can actually be understood as a kind of coping mechanism. It’s a careful staging of life and work, a necessarily low-key basking in noncommittal expressions of disavowed emotional states like frustration or laziness.

Indirect speech is also an arena where “stickers” — which are basically GIFs and tiny images with WeChat’s DRM attached — shine. Stickers have no direct equivalent elsewhere, having evolved to meet the Chinese web’s very specific needs for visual expression. Their kaleidoscopic intertextuality is the result of over two decades of shape-shifting through conventions, norms, and censorship. Today you can see in stickers remnants from custom emoticon sets that circulated on Chinese message boards in the mid-2000s, the “panda-head” meme images that were dominant on QQ in the early 2010s, and the expressive cartoon animals popularized by Korean chat app LINE’s own sticker platform, which was launched in 2012. They have also become crucial to communication where the implied is preferred over the stated. They provide an everyday shared cipher, a way of hinting at something without stating it outright.

Stickers have become crucial to communication where the implied is preferred over the stated

Stickers have an expressive range that other chat apps, notably WhatsApp and Meta Messenger, cannot replicate. They aren’t just “reacts,” like bitmojis or emotes, but a language for lives thrown into and inhabited completely within WeChat. Stickers enable ways to signal online what Tim Markham in his book Digital Life calls “being-in-the-world” — allowing for acts of “observing, barely noticing, responding, not responding and moving on” — in an app unsuited to handle these complexities of social lives. On the WeChat interface, the button to open the sticker drawer is placed right next to the empty message prompt, where you’d expect to find “Send Message.” For rote, template-driven conversational settings — good mornings, thank yous, acknowledgements — they’re a single-tap affective shortcut, easier to use than images.

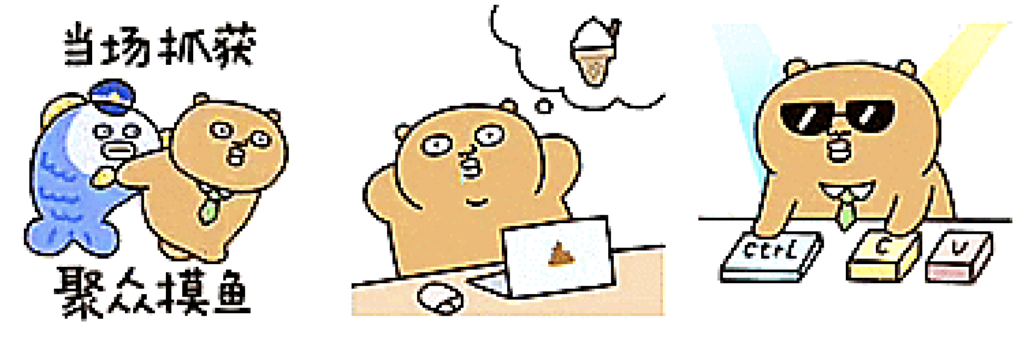

You can import any image into WeChat to build a personal collection of stickers, alongside a staggering diversity of “packs” that are available for download on a marketplace. Sticker packs can be based on pop culture figures (pop star G.E.M., law professor Luo Xiang, and the 2022 winter olympics mascot Bing Dwen Dwen all have their own sticker packs), feature original characters with elaborate worldbuilding (“Duckyo Friends” and “What Cat?” are a few personal favorites) or be delightfully situational (“annoyed designer responding to client requests,” “workout bro”). As with memes, a range of templates for stickers have developed that can assimilate new trends as they emerge. Artifacts from the early message-board era of Chinese web culture, such as the cult around depictions of former Chinese premier Jiang Zemin, survive today purely as circulating stickers. Government agencies, most disturbingly the Beijing Anti-Terrorism Police, now actively circulate WeChat stickers that reflect agency propaganda.

Stickers are tagged in WeChat with the phrases they represent — type “tired” for instance, and WeChat will autocomplete with sticker suggestions from your collection. This has helped stickers mutate into a language of their own, a densely referential web of pop-culture GIFs, animated illustrations, meme captions, text-based wordplay, and warped emojis. In China they are how online slang is mainstreamed and how hyper-specific emotions like “let it rot” find expression. The level of profanity and violence they can exhibit suggests that stickers are relatively uncensored, compared with other aspects of the Chinese web. Fluency in sticker use can feel skillful, like a slick online agility. The freewheeling, riotous joy of sticker-laden conversations is often what makes WeChat’s stranglehold on everyday online life bearable.

Sticker pack: What Cat

Behind the normalized use of stickers is an entire sticker industry, facilitating the production of idiosyncratic feelings as tradeable objects. Stickers are big business, part of what might be called a “moodboard industrial complex.” In a familiar pattern from internet platformization, what starts as a vast level of user production to plug critical gaps in an app’s capabilities becomes commoditized by third-party producers and later by the app itself. Large studios now churn out cartoon bestiaries of ducks, shiba inus, cats, and pigs, creating packs for every imaginable conversational scenario, and there are fierce fights over IP control of recognizable sticker characters. WeChat’s unchallenged dominance over the social web in China perhaps made this inevitable, but the fact that stickers have survived this conversion into assets with their creative energy largely intact speaks to their expressive power.

Stickers could be understood as a more quotidian version of what Asian Studies professor Margaret Hillenbrand, in her book Negative Exposures, theorizes as a “photo form”: media that involves a “labor of decipherment [that] binds people together,” creating intimate, interpersonal “coded archives” of clarity, in-jokes, and shared meaning. She draws on lingering (and clandestinely circulated) images of traumatic and powerful events in China from the long 20th century — the Tiananmen Square massacre, the Cultural Revolution — to show how photo forms function within suppressive environments as modes for visualizing what is hard to say aloud.

It may seem strange to apply a theory developed with respect to such significant world events to stickers, a medium primarily concerned with circulating images of lazy cartoon ducks and the like. But that is part of the point. Stickers reveal how the realities of public secrecy in China within the culture of the everyday have crystallized. With stickers, the tactics of visual ambiguity, remixing, humor, affective masking, irony, and ambivalence — once the preserve of artists dealing with significant political events — have become a primary part of mundane visual expression.

Visual ambiguity, affective masking, and ambivalence have become a primary part of mundane visual expression

One of Hillenbrand’s key points is that photo forms don’t “blow open” public secrecy through dramatic reveals of what was once hidden but rather provide “strategies of defamiliarization,” ways of seeing a parallax view that encourage viewers to “gaze anew at the social world.” Their impact is iterative, building through habitual exposure a language of secrecy and shared connection. They thrive where “knowing what not to know” is a structuring force. In giving spectators a “code to crack,” photo forms allow for liminal, conspiratorial spaces of emotional expression. Stickers can likewise help bind marginalized groups together: queer-coded stickers, stickers for niche fandoms, stickers for people in particular workplace conditions. In large WeChat groups — perhaps the single most common mode of social engagement for most Chinese today — sticker choices function like tote-bag slogans or T-shirt patterns: the means by which beliefs and interests are announced and decoded.

In recent years, stickers have sustained — perhaps even boosted — buzzwords that capture disquiet and disaffection among young Chinese. Phrases like the widely reported “lying flat,” “touching fish,” and others are kept alive via sticker circuits, capturing an ironic recognition of workplace exploitation that official media downplays. In their tiny, playful, riotous probing of “taboo” feelings, stickers, in the words of Shaohua Guo, foster “micro-ruptures” within hegemonic formations. They become repositories of trending speech that can be “unsanctioned” or overtly political — an agglomeration of photo forms adding up to a “coded archive” of jokes, opinions and punch lines, both “occluded and blindingly obvious.”

Half-Hearted Bear at Work. Text on left: “Arrested for Inciting a Slacking Incident”

Stickers represent a front in a normalized, everyday struggle against opaque platform logic. The photoform on WeChat — whose dominance over Chinese social life is now approaching a decade — is perhaps just a few clicks down the timeline from the rest of the world. The dynamic it captures reappears, to some degree, within every social platform with more or less totalizing ambitions. The attunement to algorithmic logic, the intuitive understanding of a platform’s content moderation through constant probing and boundary testing, can be seen in, for instance, TikTok “algospeak,” where users swap in code words like “unalive” to replace phrases like “dead” that might be down-ranked by algorithms that control post visibility. But the logic of the photo form also appears as the organizing principle behind both social movements (such as anti-junta activism on Facebook in Myanmar) and reactionary subreddits: An enduring kernel is warped and remixed to survive and remain available in the form of coded invitations into conspiratorial spaces. Such tactics codify a kind of counter-hegemonic “common sense” in online lives dominated by platforms that aspire to creep further and further into our daily lives.

Repression doesn’t just stop expression but causes it to morph into new forms

While the Chinese web is often understood as purely preventing expression through censorship, this discursive space that stickers have carved out under WeChat’s shadow recalls Michel Foucault’s conception of power as productive: Repression doesn’t just stop expression but causes it to morph into new forms. At the same time, these new forms provide new, ambivalent means of solace.

“Insofar as silence [is] stifling,” Hillenbrand writes, “small acts of speech may bring their own vital relief.” This applies to stickers as well. Popular stickers reveal the opposite of what the official diktat of a “positive energy” media landscape in would like to project: a moodboard overflowing with a persistent sense of unmoored precarity, a sense of lost civic belonging. Gazing at the parallax everyday worlds that stickers offer, it can be challenging to recognize them as a necessary yet fleeting escape vent when they also evoke a life precariously balanced between the “implied” and the “stated.” Even as they offer opportunity for expression, they speak to a seemingly permanent rift that subjects must internalize and continually navigate. A lot of stickers are defeatist, often reinforcing the conditions of precarity, signaling an anticipatory negativity that things will, without question, turn out bad. It’s not unusual in Chinese workplace WeChat groups to receive disturbing stickers that seem to imply violence or suggest self-harm.

When I first became obsessed with WeChat stickers, I thought of them as examples of “anesthetic feelings,” a term of Lauren Berlant’s for expressions that protect against the over intensity of feeling — “a predisposed disappointment,” they write in Sex, or the Unbearable, “to avoid the crushing feeling of actual disappointment.” The connection was suggested to me by Asa Seresin’s description of “heteropessimism,” in which individuals perform their disidentification with heterosexuality to ultimately demonstrate their allegiance to it.

Stickers help solidify their own performative disidentification against a “positive energy” mainstream, offering subtle templates of affective response that allow people to access (and normalize) “unspeakable” emotions too unseemly for a public persona, such as depression, anger, confusion, or lust. Within WeChat’s restrictive templates for online life, stickers’ ubiquity opens a space for a shared affective repertoire that runs counter to the uses that the app and the state want to prescribe. What can occur in that space is not necessarily or automatically a form of impactful resistance, but it does open a space of ambivalence and possibility.

Between the technical overreach of WeChat as a platform and the emotive gaslighting of the Chinese state, mapping this space that stickers carve out can reveal new, hopeful, forms of relationality — not just for WeChat users within the Chinese web but to everyone who is or may soon be thrown under a super-app’s all-encompassing logic. Perhaps stickers offer the hope that undisciplined improvisations can thrive no matter what digital platforms push on us as the new normal.

The conditions of precarity that gave WeChat stickers their present form are global, and sticker-like venting of unseemly emotions is visible across the internet. As Hillenbrand says in a recent talk, “Undisciplined feeling is a legitimate response to the cliff edge of precarity.” It may not be cartoon ducks all the way down, but the “sticker mode” — these habituated practices of disavowed basking in compromised digital spaces — will matter more and more. WeChat stickers teach us how to read these parallax worlds, seeing improvised agency break through a platform’s pre-programmed totality.