Sidewalk Labs’ Toronto headquarters is located at 307 Lake Shore Boulevard, right on the city’s waterfront. The building’s exterior is brightly painted in the industrial-gentrification chic style. The interior is part of a community outreach effort, filled with a slew of engaging dioramas and exhibits about technology and cities. But in many ways, the floor beneath is the space’s centerpiece. As visitors move from exhibit to exhibit, they walk across a plywood surface of hexagonal tiles — a system that Sidewalk Labs and designer Carlo Ratti, the director of the Senseable City Lab at MIT, call the “Dynamic Street.”

The real tiles — which will be made of concrete and be capable of housing sensors, signage and heating coils to melt snow — will make up an urban surface system that Sidewalk hopes to deploy across its project area in Quayside, right outside 307’s door. Dynamic Street has been designed to enable the elimination of curbs, introducing one flat hardscape that can change from street to sidewalk to plaza to parking as needed, with tiles changing colors to designate the appropriate usage. The exhibits at 307 try to give people a feel for this fluidity, letting them play with a “reconfigurator” that digitally simulates “urban scenarios of their own,” modifying things like density and street usage on the fly, instilling the idea that the tiles can be used at will to “swiftly change the function of the road without creating disruptions on the street.”

Instead of the glittering city of the future, Toronto is being given an industrial redevelopment with panopticon qualities

The Dynamic Street is also a promise that road maintenance will be easy and undisruptive, becoming a matter of swapping out damaged tiles as needed and not involving the costly process of street closure and repaving, which requires heavy machinery and dozens of workers on site. The goal is to make Quayside a place, as Sidewalk states in its Master Innovation and Development Plan, “where the only vehicles are shared and self-driving … [and] where streets are never dug up” and the streetscape “responds to citizens’ ever-changing needs.” Given the other controversies over data extraction and usage surrounding the Quayside project (described for instance in this CityLab article by Laura Bliss), the Dynamic Street seems relatively harmless. Besides, who would want to defend the inconvenient and expensive process of typical road maintenance? According to the CBC, the City of Toronto expected to spend $171 million (in Canadian dollars) on roadwork in 2018 and repaired more than 100,000 potholes in the first three months.

By turns a mundane and a marquee technology, Dynamic Street is the ground upon which Quayside will both physically and ideologically rest. But the Dynamic Street is a feint: It begins by promising something utopian and benign — an improved quality of life and the minimization of human involvement in that process — but the end result amounts to a hostile corporate takeover. Carrying Sidewalk’s implications to their conclusion reveals a future Quayside that has been made a technocratic fiefdom whose benefits and inevitable miseries are even more unevenly distributed than they are today.

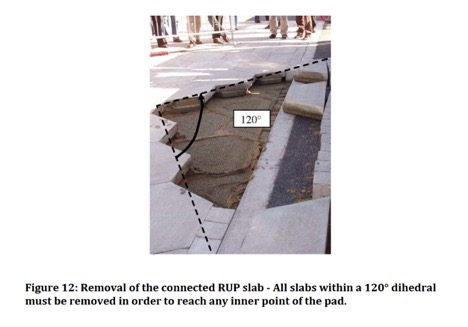

Dynamic Street didn’t arrive in 307 fully formed. The basic idea of a modular, easily replacable streetscape was dreamed up in 2012 in the research labs of the French Institute of Science and Technology for Transport, Development and Networks, or IFSTTAR. Researchers there wanted to develop a roadbed that could be “opened and closed within just a few hours using very lightweight site equipment, in restoring the initial street appearance and all its functionalities.” They tested tiles for years in laboratory conditions before carrying out field tests of the full system in the French cities of Nantes and Saint Aubin.

This system was not without its problems, however. The biggest issue was that merely placing the tiles next to each other didn’t provide enough support for vehicles traveling over them and caused the tiles themselves to crack and buckle ahead of schedule. In order to stiffen the tiles, IFSTTAR’s designers added an interlocking key along the perimeter of each tile, which would latch on to all the other tiles next to it. This increased stability but sacrificed the original intention of easy replaceability. Instead of being able to remove a single tile when it cracked or wore down, maintenance crews now had to start with the border tiles and remove row after row until they got to the one they needed to replace. Instead of making for a fluid street undisturbed by typical repaving and closures, IFSTTAR’s tiles just swapped one form of labor-intensive maintenance for another. The institute ended up scrapping the project.

Jump forward a few years. Ratti and Sidewalk exhume IFSTTAR’S hexagonal tile and add a kitchen sink’s worth of sensors and technical abilities to it without changing the basic physical shape — including that interlocking key IFSTTAR ended up incorporating. In a February 25 tweet, Sidewalk Toronto shared a video of a concrete prototype of the tile being installed that clearly shows the new tile being carefully moved into position, locking in with its neighbors. Not only that, the video shows the installation requiring a crane — not exactly the seamless process that Sidewalk had promised. Considering that easy replacement is one of the arguments used to position the Dynamic Street as an essential technology, the fact that this is impossible with the current design seems like it should be a cause for concern.

So the few promises Sidewalk has made thus far about their tiles — that they’ll make maintenance a breeze, that they’ll allow the street to become a fluid surface — are misleading at best. This should be no surprise, as Sidewalk’s grand plan seems to have been about misdirection from the very beginning, presenting a fancy real estate development scheme and data extraction machine as a technological utopia. Instead of the glittering city of the future, Toronto is being given an industrial redevelopment with panopticon qualities, and instead of being given the street of tomorrow, Sidewalk is offering a concrete slab with some lights and heating coils in it.

The tiles are likely just one stepping stone toward the end goals of Sidewalk’s megaproject, which remain mostly opaque but which almost definitely include the conquest of as much of Toronto’s eastern waterfront property as possible. Sidewalk has plenty of more overt tricks up its sleeve: there’s the $980 million equity investment proposed, along with the more typical promises of jobs (93,000 “total jobs” by 2040) and economic growth ($14.2 billion in GDP output beginning in 2040) that only a corporate behemoth with Alphabet’s backing can provide. If that gets stuck in the mud, the project’s easily overlooked infrastructural elements — access conduits, delivery tunnels, and the Dynamic Street — will serve as a means for enacting a clandestine transfer of city responsibilities into corporate hands.

The project’s easily overlooked infrastructural elements, like the Dynamic Street, will serve a clandestine transfer of city responsibilities into corporate hands

Throughout the development process, Sidewalk has, as Bianca Wylie has noted, “weaponized ambiguity” when faced with tough questions — such as, for example, whether critical infrastructure within its suite of “public realm innovations” will even work. This is not an engineering mishap but a feature. In the Master Innovation and Development Plan the company acknowledges that the Dynamic Street’s “new approach to street systems would require changes to existing regulations and operations.” Practically speaking, this likely means that Sidewalk would exploit its position as the creator of Dynamic Street to secure an exemption from Toronto’s typical 20- or 30-year road maintenance cycles. The project area would thus become, in a small way, a separate Toronto within Toronto. Though road maintenance is a minor example, if Sidewalk could duplicate this handover of power in other spheres, elected officials and public services could end up being excluded in favor of Sidewalk’s own “expertise,” essentially creating a vertically integrated monopoly within Quayside.

When Sidewalk presents the Dynamic Street as a fluid, self-contained system, there is an embedded demand that work on the system, specifically maintenance work, also become self-contained. Elsewhere, Sidewalk has been explicit about this intention, taking the messy or ugly elements of urban logistics or maintenance and automating them or burying them in tunnels. Generally speaking, in the Quayside of the future, maintenance appears only rarely and usually well out of sight — by design.

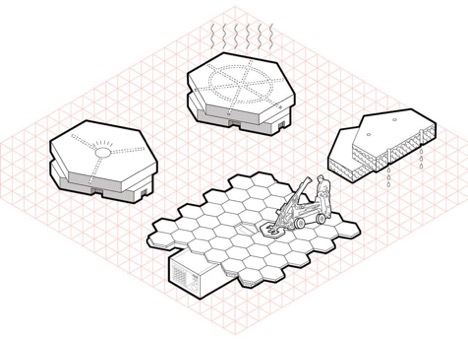

This is an argument with a specific class dimension: “Smart” engineers and immaterial workers will be celebrated, but the non-tech workers, service workers, and maintainers will be pushed out of sight and, hopefully for Sidewalk, out of mind. Consider the worker in this diagram, taken from Sidewalk’s Master Innovation and Development Plan:

Many of Sidewalk’s other renderings feature happy citizens, leisurely enjoying their environment in a sort of perpetual weekend. It’s not a stretch to realize these people — the people that Quayside will be built for — are the “knowledge workers” who will inhabit the coworking spaces to come (or the Google campus to be built on nearby Villiers Island). But the person in the diagram above is not only at work but working on the city itself, doing the maintenance labor that already often goes unconsidered.

What will such workers’ experience of Quayside be like? They are depicted as a system unto themselves, with no work team or heavy equipment required, such as the crane in Sidewalk’s video. This worker can be deployed automatically, embodying the same fluid responsiveness that characterizes the rest of the Sidewalk’s marketing. To put it simply: If the maintenance work can’t be done by robots, Quayside will demand workers act like robots — an approach that has been labeled “pseudo-AI.” Mary L Gray and Siddharth Suri’s recent Ghost Work is a book-length examination of this tactic.

In the Quayside of the future, maintenance appears only rarely and usually well out of sight — by design

Quayside will effectively exist as two cities. In one, citizens will enjoy the dreamlike novelty of streets, spaces, and services that seemingly respond to their every desire; in the other, woven in and through the first, workers will be confronted with machines that likewise demand they become more machinic. The mundane utility of Dynamic Street in minimizing disruption and suppressing repair is fundamental to this. Smuggled in as an innovation, Dynamic Street composes the base layer of Sidewalk’s minimal urban environment: a “city” free of social services, community, and solidity. Instead, the illusion of a city is carefully constructed atop a vast apparatus that exists primarily to organize capital, labor, and profit. Usually, we would call such environments factories or industrial zones. Quayside is a proposal that the factory and the city don’t just mirror each other but become each other.

Instead of allowing Quayside’s future workers the opportunity to understand and develop a relationship with their work, the requirement that the city becomes a seamless technological artifact will further alienate those workers from the city and themselves. A self-contained system such as Dynamic Street begets self-contained, equally replacable workers. Their labor is made into to a replaceable machine part. In this respect, Sidewalk hasn’t presented us with anything novel — just a refinement of the basic logic of capitalism, which has always depended on the cruel subjugation of workers. As Fred Moten and Stefano Harney write in The Undercommons, “To work today is to be asked to do without thinking, to feel without emotion, to move without friction, to adapt without question, to translate without pause, to desire without purpose, to connect without interruption.” Technological developments such as the Dynamic Street become tools of further subjugation. Marxist theorist Raniero Panzieri argues that under capitalism, “even the lightening of the labor becomes an instrument of torture, since the machine does not free the worker from the work, but rather deprives the work itself of all content.” Capitalists make work meaningless so the worker becomes meaningless in turn.

This brutal dehumanization is never complete, but it is also never total. Noel Ignatiev writes that workers constantly do work outside of what they’re paid to do, including the work of developing an understanding with the machines they are confronted with. Making the effort to “master the equipment which makes the things they need, to gain control over the work process” makes it possible for work to become “a source of satisfaction to them.” This is present in even the most thankless work.

Uncovering and understanding care takes a crucial step away from value for value’s sake and the dehumanization it entails. Simply put, care is not productive — at least by the narrow metric of specifically capitalist production. As Achille Mbembe warns, “unless we reinvent the terms of what counts and in the process resignify what value stands for as well as the procedures of assigning value, of measuring value, of exchanging value, things won’t change.” In “Matters of Care in Technoscience,” Maria Puig de la Bellacasa describes care as a social activity, “a signifier of devalued ordinary labors that are crucial for getting us through the day,” and identifies it within domestic laborers as well as industrial ones. Monique Lanoix explains in her essay “Labor as Embodied Practice” that caring work is not just an attitude, but material and corporeal labor, even though it “not produce a material commodity.”

The illusion of a city is carefully constructed atop a vast apparatus that exists primarily to organize capital, labor, and profit

If there are alternatives to the Sidewalk approach to urban development, it’s not in a more “humane” corporate approach but in a worker-centered movement that begins and ends in care. “We could imagine physical infrastructures that support ecologies of care — cities and buildings that provide the appropriate physical settings and resources for street sweepers and sanitation workers, teachers and social workers, therapists and outreach agents,” Shannon Mattern writes. An ecology of care requires a complete reconsideration of space that rejects Sidewalk’s remixed capitalist, productivist approach. Care appears only when the conversation is shifted from the delirious pursuit of profit-at-all-costs to a more thoughtful approach to the built world, centering maintenance, like labor, as a social practice.

“As a corporate fantasy, the smart city is dead,” Jathan Sadowski wrote in a recent Real Life essay. He’s right. The smart city was only ever a euphemism for corporate control dressed in technological futurism, which Sidewalk has employed to great effect. But whatever is left postmortem must be reckoned with. Smart cities’ market value — $717.2 billion by 2023 according to Markets and Markets — is rising at nearly 20 percent a year and showing no signs of slowing down. Whatever name it takes, capital’s attempts to colonize not just neighborhoods but daily life continue apace and continue to make a lot of money besides.

The world of capital is created and maintained by us, but has left us to “stand outcast and starving midst the wonders we have made,” as Ralph Chaplin put it in the union anthem Solidarity Forever. We are confronted with a hostile landscape of violence, exclusion, brutality, and yes, technological splendor. A world shaped by us is not dependent on a new imaginary, a thought experiment, or a design proposal, but followed these back to their theoretical headwaters: What if instead of capital, we put ourselves first?