“The history of the photographic book is the history of photographers and editors trying to lure and coax us into reading them sequentially, to persuade us that a visual narrative is at work.”

— Geoff Dyer, The Ongoing Moment

One likes to believe in the story of oneself. Unfortunately, as the protagonist of a life, it’s all too easy to fall into inconsistency. We act in ways that don’t match up with the larger narrative. Things happen to us that derail the plot. And so we revise, alienating ourselves further from our selves.

To access my social media, listen to music, check the weather, answer a text, look at porn, worry over my bank balance, read an e-mail, or answer a call, I place my thumb on a small circle at the base of my phone. When I sign up for a new service or website, I squint to decipher what’s called a Captcha code, which is supposed to ensure that I’m not a robot. (The frequency with which I’m wrong is starting to make me wonder.) My computer boops when I access a new app on my phone. My phone beeps when I login to my email on a new computer. I am an “authorized user” on my partner’s Apple Music account. Recently, I was “verified” on Twitter: a blue checkmark proves that yes, this is the “real” Patrick Nathan you are looking for.

A self-portrait is not its painter. We narrate ourselves based on the narratives we read in the images and personae of others

Much like a digital photograph or darkroom print, the image of ourselves we wish others to see requires extensive manipulation of color, contrast, light, and shadow. We develop variations on our personality depending on who is viewing, and we call these individual prints personae. Meticulously constructed and carefully exhibited, our entire portfolio of personae questions the concept of authentication, which perhaps only maintains validity when considered in light of its etymological root: We are indeed, as our thumbprint suggests, the author (Latin auctor, “originator”) of each and every one of these self-portraits. A self-portrait is not its painter. An essay is not its author. These personae, these images of ourselves that we call our selves, are only narratives. Filtered through the same Instagram algorithms and quoting a shared language of selfie poses, each projected self comes to resemble the others: We narrate ourselves based on the narratives we read in the images and personae of others.

Despite its technological aspirations toward documentation and preservation, photography has become simply one more way to tell a story.

In 2017, the New York Times predicts, humankind will take approximately 1.3 trillion photographs. Of these photographs, more than 75 percent will be taken with mobile phones, and many of these will be uploaded to social media or some other platform where, essentially, anyone can save them, use them privately, modify them, repost them, and re-circulate them.

Confronted with the daily tableau of cultural images, the drive to make sense of them, to organize them, can become obsessive. In this system, images are not so much looked at and copied as they are quoted. Whether juxtaposed against our larger social media archive, repurposed as memes, or posted with simple captions, nearly all images are assigned meaning or provided context; and it’s this context that serves as an expression of the self. We collect images (including words as images) as a way to remind ourselves of what matters to us, what is important, what we want to remember. The wish to make meaning, to narrate, is obfuscated by the sheer volume of images we take, make, or collect. In the ongoing commodification and consumption of images, both visual and cultural, each moment ebbs away from us; what is supposed to be a joyous activity becomes a harbinger of anxiety.

Roland Barthes, in Camera Lucida, can’t help but liken it to death: “When we define the photograph as a motionless image, this does not mean only that the figures it represents do not move; it means that they do not emerge, do not leave: They are anesthetized and fastened down, like butterflies.” Lovely to look at, certainly, but with a cost. On the other hand, the novelist and photographer Hervé Guibert had no delusions about the tomb in the camera’s eye; he knew its cost quite well: “I allow myself to be photographed, not like someone who is still alive, but like someone who was still alive at the moment of the photograph.”

In “Kim Kardashian West Is the Outsider Artist America Deserves,” Laura Jean Moore claims that female self-portraiture “upends historical norms of female representation and power, and places the power of depiction squarely in the hands of the subject.” In assuming herself and her life as a subject, Moore writes, “Kardashian West is part of an established legacy of female artists and writers who have created art from the realm of the intensely personal and confessional.” Through her Instagram account, Moore suggests, Kardashian West tells the story of herself to more than 100 million followers with total artistic agency. Her narrative is one of empowerment, beauty, and — strangely enough, via a distortion of the self — self-acceptance.

We collect images (including words as images) as a way to remind ourselves of what matters to us, what is important, what we want to remember

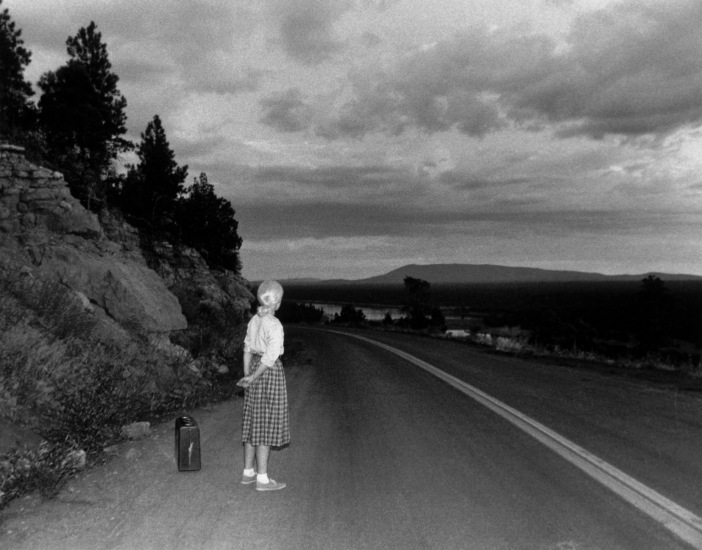

Cindy Sherman’s photography seems an inversion of this formula, suppressing “the personal” and “the confessional” despite her physical body being the subject of almost all her photographic work. In “A Piece of the Action: Images of ‘Woman’ in the Photography of Cindy Sherman,” Judith Williamson argues that Sherman adapts the traditional uses of women in art, journalism, and advertising as divining rods for dominant societal narratives: “An image of a woman’s face in tears will be used by a paper or a magazine to show by impression the tragedy of war, or the intensity of, say, a wedding. From the face we are supposed to read the emotions of the event.” In Sherman’s Film Stills project, Williamson says, “the very reference to film invites this interpretation. Film stills are by definition a moment in a narrative. In every still, the woman suggests something other than herself, she is never complete: A narrative has to be evoked.” Instead of highlighting how narrative can imbue a self with agency, Sherman’s oblique personae may be read as being deprived of complete agency. The people in her photographs are enmeshed in narrative.

In Fetishism and Curiosity, Laura Mulvey suggests that each of Sherman’s images is “a cutout, a tableau suggesting and denying the presence of a story. As they pretend to be something more, the Film Stills parody the stillness of the photograph and they ironically enact the poignancy of a ‘frozen moment.’ The women in the photographs are almost always in stasis, halted by something more than photography.”

Photographers and writers on photography often argue for divorcing photographic images from narrative. Though the lens’s limitations and the borders imposed by its frame may seem to imply a story being told, Susan Sontag warns that we must resist this temptation. In On Photography, she notes how “Photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy.” In The Ongoing Moment, Geoff Dyer observes that, in picture-taking, “there is no meantime. There was just that moment and now there’s this moment and in between there is nothing. Photography, in a way, is the negation of chronology.” Since photographs are outside of time, they cannot reveal for us — existing as we do inside of time — any true understanding of our lives as we live them. Images operate in a different dimension where time and narration are irrelevant. “Only that which narrates,” Sontag asserts, “can make us understand.”

However, where there is no narrative, we tend to create one. In a 1983 interview with American Photographer, Sherman observed the uncanny confusion many felt in experiencing her work: “Some people have told me they remember the film that one of my images is derived from, but in fact I had no film in mind at all.”

In illustrating the temptation to project a narrative upon an image, Sherman’s Film Stills reveal, too, just how easy it is to lose oneself in that image — to erase oneself with a story that isn’t your own.

Almost a year after Twitter introduced its Moments feature as an aggregate image-tableau of “things you should pay attention to,” the platform extended to users the ability to create and curate their own “moments.” I interpret this as Twitter’s take on Facebook’s equally ambiguous “life event.” On both platforms, users can author and publish in their timelines the moments they want followers to see: This is what I want you to know and remember about me. Dynamic parts of one’s life, once lived out in time, lie down flat and become images, and with all of an image’s vulnerability.

If a moment in our life is distressing to remember — to see manifested as an image — we can forget it: “Select Delete Moment to permanently remove the Moment from your profile and Twitter,” instructs one help file. “You will see a confirmation pop-up message to confirm the deletion.”

Since photographs are outside of time, they cannot reveal for us — existing inside of time — any true understanding of our lives as we live them. Images operate in a different dimension

In Regarding the Pain of Others, Sontag approaches the idea of “sponsorship” of moments at the societal level: “The familiarity of certain photographs builds our sense of the present and immediate past. Photographs lay down routes of reference, and serve as totems of causes … Photographs that everyone recognizes are now a constituent part of what a society chooses to think about, or declares that it has chosen to think about. It calls these ideas ‘memories,’ and that is, over the long run, a fiction.”

This so-called collective memory, Sontag says, “is not a remembering but a stipulating: that this is important, and this is the story about how it happened.” Reducing history like this — to “the visual equivalent of sound bites” — distorts the understanding of the past. It excludes important voices and splices unassociated events together. These snapshots, arranged in sequence, narrate the past not as it happened but as a closed, complete story. Narratives, by their nature, distort. They excise. They clip. They filter.

A quick search for the hashtag #nofilter on Instagram returns, as I write this, 169,415,808 photographs. Many of them are landscapes. Some are close-ups of flowers, trees, or handfuls of beach sand. Few are selfies. Most are sunsets, an event that occurs, literally, every day on earth. In the standard sunset photograph, the horizon is centered vertically — an equal field of murky land or water below an equally murky sky, and that brilliant wound of color scratched into the middle. It’s the color, I think, that people find so hard to believe, and what they want us to believe through their photographs. What #nofilter promises, ostensibly, is true colors, verified colors. This happened, #nofilter says; or, in a more familiar phrase: This is a true story.

But even those supposedly real sunsets are, in a sense, filtered. The scene’s very selection as a photograph, as well as its frame — the edge of what we see — create a narrative of boundaries: this is what was seen, and that is whatever wasn’t photographed, whatever the photographer excised from the past. “Every time we look at a photograph,” John Berger reminds us in Ways of Seeing, “we are aware, however slightly, of the photographer selecting that sight from an infinity of other possible sights.” The ubiquity of #nofilter exposes the “preserved moment” for the idyllic lie that it is — an artful re-creation. Similarly, its very usage — going out of one’s way to promise #nofilter — contaminates the photograph with an expression of selfhood; it tells the viewer the story of just how badly the photographer wants to be believed.

In his 1991 memoir, Close to the Knives, artist David Wojnarowicz, though reluctant to call himself a photographer, describes how his experiments with a camera taught him about representation and power: “If you look at the newspapers you rarely see a representation of anything you believe to be the world you inhabit,” he says. “This is called information control.” But this controlled view of the world, he argues, can be countered:

As a person who owns a camera, I am in direct competition with the owners of television stations and newspapers; though my gestures of communication have less of a reverberation… To me, photographs are like words and I generally will place many photographs together or print them one inside the other in order to construct a free-floating sentence that speaks about the world I witness. History is made and preserved by and for particular classes of people. A camera in some hands can preserve an alternate history.

Through his art and his protests, Wojnarowicz was instrumental in demanding and creating visibility for the hundreds of thousands dying and suffering from AIDS in the late ’80s and early ’90s, after the Reagan administration refused to acknowledge the disease. His narrative of images is an act of resistance against an imposition of power, an effort to prevent an erasure. It holds a political administration accountable for its complicity in this hatred and violence, for its gamble that a genocide would be remembered, in the future, as “God’s punishment.”

For many of us, however, the practice of taking, gathering, and sharing images is simply a resistance against ourselves. The narratives we tell through our creation and consumption of images contradict our lives as we live them. For example, in a 2016 “Modern Love” essay for the New York Times, Sage Cruser described the role that social media played in a recent relationship, doomed from the beginning. To assuage her anxiety about being “the rebound girl,” she indulges in crafting an impenetrably perfect relationship in images: “On Facebook, I was able to exclude the negative … and showcase not only how I wanted others to see us but how I wanted to see us.” This didn’t work, and she describes how, later, she quarantined these memories, dropping them all into a folded buried in her computer called “Do Not Open.” From there, she writes, it was easier to heal.

In our personal lives, such narrative revision is a process of cleaning that has no clear boundaries, no obvious end point. Excessive deletion — obsessive emotional cleansing — can fabricate a persona that’s closer to object than subject — a surface without subjectivity. In The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson posits identity as an ever-shifting amalgam of experiences and relationships we drag along with us as we sail on, like Homer’s ever-patched and repaired Argo. To deny certain experiences and relationships is to punch our hulls full of holes.

Surrounding oneself with images is a form of aspiration; we survive on the breath of our future self, what we might become.

Until quite recently, the most common form of images most of us came across was in advertisements. These images — which, in Ways of Seeing, John Berger calls “publicity images” — “belong to the moment … They must be continually renewed and made up-to-date.” Yet as saturated as we are with these publicity images, “they never speak of the present. Often they refer to the past and they always speak of the future.”

Just as the photograph entombs a moment in time and divides the past from the present, the publicity image, Berger says, “is always about the future buyer. It offers him an image of himself made glamorous by the product or opportunity it is trying to sell. The image then makes him envious of himself as he might be.” In a capitalist culture, we curate the images that excite our desire to spend money to become someone else, even if it’s only our past self who envies us.

If photography is our convention, even compulsion, for recording, understanding, and narrating the past, ads can be understood to mirror that compulsion, looking forward into an equally fictional future. We are the canvas upon which ads paint their narrative.

The more we storify our pasts and futures based on images, the more the self itself corrodes, until we too may remind someone of a narrative uncannily familiar, a film never made, a life never lived

With social media, this reaches a more sophisticated level, where every image — owing to the nature of the medium itself — can be seen as an advertisement. We can broadcast our own personal advertising campaign: This is what I’d like to be. Friends and strangers alike can witness our aspirations as an aggregate (scrolling through our tableau of images) or in real time (liking and sharing these images as we post them). Whatever we share may be viewed through the context of what it might say about us, and the envy that might provoke. For example, a shared image of a work of art becomes a destabilizing element of glamour: I wish I was as cultured as you, or I wish I traveled as often as you. An image of dinner is not about food but envy: Not only am I not eating this, I wasn’t even good enough to be invited.

As early as 1936, Walter Benjamin could write about “the cult of the movie star” and the “shriveling of the aura” of the actor, the actual person, in favor of “the spell of the personality, the phony spell of a commodity.” Sontag described a culture in which “people themselves aspire to become images: celebrities. Reality has abdicated. There are only representations: media.” The more image-like we become — the more filters we overlay onto our faces and bodies — the more we can measure ourselves in relation to our “following.” The more we storify and cleanse our pasts and futures based on images, the more, like in Sherman’s Film Stills, the self itself corrodes, until we too may remind someone of a narrative uncannily familiar, a film never made, a life never lived.

Even before he began to die, Guibert observed in his journal how his life seemed to be “a foreclosed novel, with all of its characters, its eternal loves … its ghosts, and there is no further role to fill, the places are taken, walled up.” Years prior, he’d written of his hesitation to indulge his passion for photography: “This attraction frightens me … out of one’s life one could cut out thousands of instants, thousands of little surfaces, and if one begins why stop?” Indeed, if one’s narrative of resistance goes against the actual life one is living, when do you stop revising?

In what darkness does one preserve the living self, or — for lack of a better word — the soul?

The photographed moments of the past are entombed; they are immortalized in their severance from what is happening to us right now. Their story is over. Images of the future are equally severed, stretching out into another narrative we curate and navigate. Between the two narratives, by definition, we have the present. Between the glut of images that comprise our past and the (far greater) plethora of images that tell the story of our future — for better or for worse — the present itself feels as though it barely exists.

We haven’t left ourselves much room to link the narratives in a way that makes a complete, meaningful life story. In this claustrophobic space there is barely room to breathe, and in the moment of suffocation it’s natural to claw and scratch at whatever we can to get by, to cope with the panic. It’s natural to feel as though one’s soul is fading, and it may, in an increasingly photographed world, become necessary to savor its transience, to allow instead the moment itself to fade.

Barthes, in Camera Lucida — his final book — wrote about the ignorance of all the world’s young photographers, “determined upon the capture of actuality,” yet who “do not know that they are agents of Death.” After he died, Sontag recalled how he “had beautiful eyes, which are always sad eyes.” When Sontag died, her protégé Sigrid Nunez found the shock of it — “to have been such a person, someone who struck others as too strong and tough, too alive to die” — almost an antidote to Sontag’s “insistence on her exceptionalism, her refusal to admit that her case was hopeless, that death was not only inevitable, not only near, but here.”

In The Ongoing Moment, Dyer recalls a conversation he once had with John Berger, who some years before had visited the legendary photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, then in his eighties. “What struck Berger most about Cartier-Bresson,” Dyer writes, “were his blue eyes which, he said, were ‘so tired of seeing.’” When Berger died, earlier this year, Dyer professed that “No one has ever matched [his] ability to help us look at paintings or photographs ‘more seeingly,’ as Rilke put it in a letter about Cézanne.”

When Guibert did begin to die, recording in journal entries and photographs the ongoing deterioration of his body from AIDS, he observed how “the only things I want to photograph now are at the edge of the night.” In one of life’s strange and haunting, daresay soulful echoes, Dyer recalls Diane Arbus’s fascination, late in her life, “with what could not be seen in photographs.” In one of her final lessons to her students, she confessed to the pleasures of what is not seen in photographs, what is hidden in the dark — “An actual physical darkness and it’s very thrilling for me to see darkness again.” Arbus was 48 at the time and one of the most renowned photographers in America. In one of her last projects, she photographed the disabled, the mentally ill, unshapely women, the scarred, and the burned, showing these unrepresented people in unforgettable ways. We look now where few would look before. It’s these photographs for which she is most well known. Not long after they were first exhibited, she took her own life.