In the early hours of November 9, 2016, the media habits of Donald Trump’s electoral base became an unavoidable concern for mainstream media. The rending debates over missed signs of electoral and popular discontent began that very morning, rather than months before.

The social media feed had long been a symbol of ideological difference: According to liberal and centrist media, the polarization of American politics was best exemplified in the curated timelines and newsfeeds of voters. Now an abstract concern about the nature of political discourse seemed like a concrete problem in need of correction. The solution, for some publications, was “bursting the bubble,” by encouraging readers to consider the news feeds of their political opponents — an attempt to combat the effects of technological intermediation and curation with more intermediation and curation.

The Wall Street Journal, for instance, simulated side-by-side red and blue feeds: One could see a Media Matters paean to Obamacare next to a meme from the National Pro-Life Alliance that accused one of the health plan’s architects of callous indifference to the lives of unborn children. Echochamber.club, a newsletter founded in June 2016 by Alice Thwaite and written with the help of outside contributors, uses social media analytics to find countervailing views to those held by “Western ‘liberals,’ ‘progressives,’ and ‘centrists.’” Thwaite claimed, in an interview, “I’m hoping to help equip liberal thinkers for challenges to their views.” The Guardian’s ongoing “Burst Your Bubble” series, which has been publishing weekly since November 2016, uses human curation to provide readers with five “conservative articles worth reading to expand your thinking.” (Disclosure: I am an occasional contributor to Guardian US.) The column’s curator, Jason Wilson, told the Nieman Lab’s Laura Hazard Owen, “If we see our opponents as people who disagree with us, but have, in other ways, pretty similar lives and pretty similar limitations to us, I think that helps us engage with politics in a more realistic way.”

In addition to their faith in the power of curation — either human or technological — to faithfully convey the experience of foreign newsfeeds, these products embody the belief that consumption of countervailing opinions can lead to meaningful, productive engagement; and that consumption is a form of engagement at all.

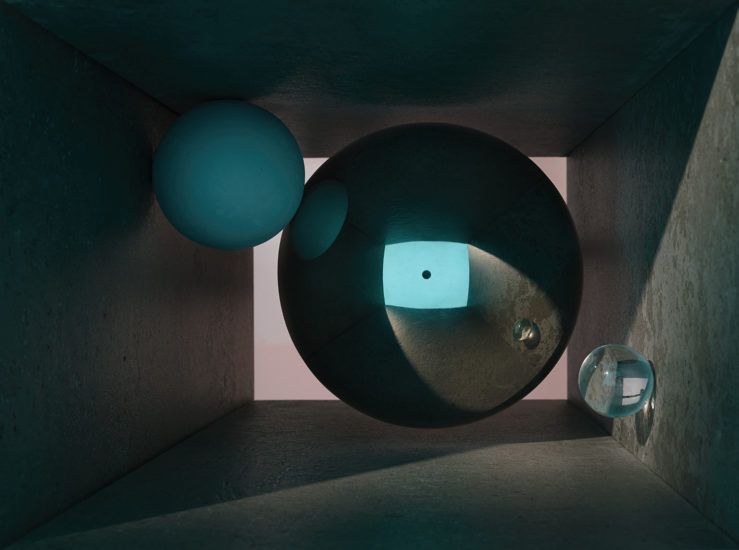

Bubble-busting services arise from the intuition that personalized newsfeeds have become meaningful political forces, an idea that is at once correct and misdirected. It’s true that feeds, like Facebook’s, help to form and reinforce our identities. The juxtaposition of political memes, photos from friends and family, and what passes for political news is powerful insofar as it elevates all content typologies to the status of a personal statement. Articles in this context needn’t be read before being shared; their primary use is in signaling the sharer’s worldview. Newsfeeds cohere a user’s politics in one place, forming, with their peers, a context that resists attempts at reproduction.

On Facebook or Twitter, the content of an article is never the whole story; often its reliability is not the point

Bubble-bursting, as an intellectual undertaking, is supposedly a means to the more important end of persuading fellow voters and building new coalitions. (This is what separates it from the sort of contrarianism for contrarianism’s sake associated with publications like Slate.) In their attempt to bridge the solitudes of social media, however, these services strip away the information most conducive to persuasion. News services that purport to curate opposing political viewpoints cannot reproduce the social milieu in which content is shared. The images and personal details that populate newsfeeds are better clues to a person’s political outlook; it is of little use arguing over the content of an article without any knowledge of the person with whom you’re arguing, any reference to how these issues might affect their lives, or how their lives might affect their biases.

Bubble-bursting services might impart their users with skills to engage with articles, but not necessarily their readers.

Editorial products usually seek to feature reliable sources, but if the goal is to bring in views ignored by its audience, the merits of this bias toward sensibility is unclear. Echo Chamber’s guide to Russian-American relations links to articles from the New Yorker, the Atlantic, and the Guardian; the Guardian’s “Outside Your Bubble” links to Breitbart, though its roundups tend to be heavy on older outlets like the National Review. In its guide to the alt-right, Echo Chamber links to Milo Yiannopolous’s “An Establishment Conservative’s Guide to the Alt-Right,” but it is unclear whether the reader is supposed to be learning to sympathize with establishment conservatives, or engaging with the overtly racist “Alt-Right” itself. And while there may hypothetically be some use in learning the “facts” of Pizzagate, the details of an article on the subject have limited explanatory value when it comes to the underlying phenomenon. (Knowing that “cheese pizza” is believed by some to mean “child pornography” is the hardly the most salient point of that episode.) Here, as ever, these services elide the difference between conservative views and stories that a conservative might encounter in their newsfeed, conflating reasoning, wishful thinking, and bile.

On Facebook or Twitter, the content of an article is never the whole story; it is but the jumping off point for signaling and discussions by the very cultures bubble-bursting services seek to explain. What proves most galvanizing on social media is often unreliable; often its reliability is not the point. An editorial product that includes known fabrications would also be suspect, of course — fake news and media polarization are serious problems in large part because there is no obvious curatorial logic that solves for them.

Bubble bursting encourages engagement in an idea alone. Articles meant to represent opposing viewpoints, when consumed together, build an incomplete picture of an imaginary foe who does nothing but read tendentious articles. Echo Chamber never makes clear why it’s important to know why people accept lines such as “[Putin] has an 86 percent approval rating amongst Russians. Consider Obama’s average approval rating is 49 percent — it’s impressive!” People who believe such things surely exist, but the composite character created here is imaginary, the product of editorial and curatorial decisions. This attempt at encouraging engagement is as likely to produce eye rolls for its rote re-hashing of state propaganda; it uncovers little about why people believe what they do, or about the consequences of those beliefs. “We’re not gonna send people there,” Guardian curator Jason Wilson told Harvard’s Nieman Lab with reference to white nationalist sites like Stormfront. “I read that stuff, but it’s not particularly productive to send our readers to that sort of thing.” Pretending that white nationalism is not represented by mainstream conservatism seems hardly productive.

Debating the editorial decisions made by these services presupposes that they are fundamentally worthwhile — it assumes that escaping one’s bubble in this manner is a social good, and that political dynamics work in curatable binaries. The Guardian’s “Outside Your Bubble” and its counterparts effectively reproduce the dynamics of the seminal political talk show Crossfire, which aimed to provide views from both ends of a narrowly defined political spectrum. At its best, Crossfire was full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. Most of the time, the show and its derivatives compelled viewers to believe that truth existed somewhere between the two poles it offered. This is centrism as service.

Media companies have been playing this game for decades: compelling viewers to believe that truth exists somewhere between the two poles it offers. This is centrism as service

Media companies have been playing this game for decades. The Wall Street Journal or the Economist offer visions of conservatism that are palatable enough for center-left readers to consume; persuasive or not, they help define the parameters of political debate. The New York Times and refrains from the 1980s and ’90s like “even the liberal New Republic” serve a similar purpose of defining a center-left that effectively denies the existence or viability of leftist ideas. The more recent, contrarian bent in digital media — the hot take as a fleetingly valuable commodity — is a more contained form of bubble-bursting; its provocative nature exists primarily in relation to an arbitrarily defined center. In that way, centrism-as-service is a logical extension of how media companies have long operated: predetermining oppositional viewpoints to reinforce the narrow parameters of political debate.

The simplicity of a bubble is part of its appeal: Life outside one’s newsfeed is necessarily messy, a political wilderness containing a great many viewpoints. Services seeking to tame this wilderness tend to evince a nostalgia for “simpler” times, when “reasonable” conservatives and liberals could negotiate a fair and acceptable compromise, as if this were ever the case. Coalitions always need to be built after electoral losses, but there are more options for coalition-building than centrism-as-service suggests: These services do not consider the possibility of being outflanked on the left. Their implicit suggestion is that the only coalitions that exist to be made are somewhere to the user’s right; services aimed at expanding their users’ political imaginations can have the opposite effect. The idea of finding allies to the left is at odds with the operating logic of bubble-breaking services, which reproduce political media’s conception of centrism. Taking in a countervailing viewpoint feels like participation in democracy, but when done in this matter it just serves to reproduce the orthodox binaries of party politics.

Taking in opposite viewpoints feels, at least, like making an effort. If slogging through articles presenting Bashar al-Assad’s perspective on the situation in Aleppo feels like a punishment, that’s because it’s meant to be. Services like echochamber.club are, if nothing else, a way for ostensible liberals to flay themselves for a loss they hadn’t predicted. At the same time, they also encourage much of the complacency that resulted in this blindsiding.

Understanding life outside your bubble is fundamentally about understanding where you stand in the world. Curated newsfeeds are good at showing users how they resemble others in their community. Learning about the world beyond is a useful form of negative identity formation: It tells you about who you’re not. Centrism services are very good at telling you who you’re not. In forming oppositional identities for their users, the likes of echochamber.club ultimately serve to ossify the very dynamics they’re meant to counteract. The view they provide is likelier to create a stronger sense of superiority than a productive empathy. If anything, it is likelier to encourage the factionalism these services seek to undermine.

Factionalism is not inherently problematic. At sufficient scale, a faction can be a working coalition that achieves meaningful change. The logic of bubble busting leads to a middle-of-the-road conviction that all reasonable people should believe the same thing. Such an outcome might be preferable to Trumpism. But that is the definition of damning with faint praise.