My first job in journalism was as an editor at gay and lesbian newspaper in Toronto in the mid-1990s. Our offices overlooked Church Street, the main drag of the city’s gay village. Out the huge windows, a queer world lay before us: up the block, a community center and a drop-in for teenagers; down the street, a theater company; in between, two bookstores, a half-dozen bars, a few bathhouses, a video store that stocked mopey gay classics like Personal Best and Boys in the Band, a shop that sold feminist sex toys and “Silence = Death” T-shirts, and a low-rise filled with AIDS organizations and support groups.

Across the street was a coffee shop, with a wide set of steps leading up to its entrance. During the day, cups in hand, people lolled there like sunning lions; at night the steps were taken over by raver kids and hustlers. When production at the paper slowed down and we had nothing to do, we’d stand at the windows and watch the crowd below: the wide-eyed kids fresh from whatever small town, the regal queens strutting, the activists in leather jackets passing out free condoms, the butch dykes in flannel shirts with earlobes full of studs, the wispy HIV-positive guys lowering themselves on shaky legs to rest on the steps.

The search for community was high-level spy craft; it meant digging for intelligence without blowing your cover

This is how we lived then, with death inflecting the everydayness of getting a coffee, flirting with a stranger on the street, working at a community paper. One of my responsibilities was the obituaries section. Every issue I filled my designated pages, sometimes asking the designer for more, with tributes to men dead from complication due to AIDS — many of them, like me, in their early 20s. We were 15 years into the AIDS crisis by then. The memorial in the park up the street was already etched with hundreds of names.

Looking back, it was a wonder I’d found my way into this community at all. No one grows up learning to be queer, not then, anyway. If anything, we intuitively knew how to hide any tells: to look away from other bodies in the gym class locker room, furtively sneak books out of the “homosexual” section in our hometown library. The search for community was high-level spy craft; it meant digging for intelligence without blowing your cover. We used the technologies we had at hand, trading news and gossip within the safety of our bookstores and bars, and out in public signalling each other with the cut of our jeans or a lingering gaze. Camp was a technology, too, as Susan Sontag observed; that clichéd, trademark gay archness was “private code, a badge of identity even.” Back in the 1960s gay men in Britain sized one another up, communicating in a near-ultrasonic range with a slang called Polari. In later years, we still spoke in code: Is he a friend of Dorothy’s? Does she play for our team? Outsiders neglected by the broader culture have always found ways to make tools of their own.

I’m too young to have witnessed the beginnings of the AIDS tragedy. David France, in his new book, How to Survive a Plague (a companion to his stunning 2012 documentary), recalls a vigil in New York’s Central Park in 1983: “The plaza was crowded with 1,500 mourners cupping candles against the darkening sky. A dozen men were in wheelchairs, so wasted they looked like caricatures of starvation. I watched one young man twist in pain that was caused, apparently, by the barest gusts of wind around us … My friend’s mouth hung open. ‘It looks like a horror flick,’ he said. I was speechless. We had found the plague. From there, it was an avalanche.”

As the plague struck New York, it struck the gay communities in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Berlin, Montreal, Miami, Toronto. My older colleagues — men and women who’d come of age during the separatist, hedonistic, radical 1970s — lost entire circles of friends within months and weeks in the 1980s. They told me about lovely young men who shriveled down to their bones overnight, their skin blossoming with lesions; about hospitals barring boyfriends from visiting their dying lovers; about funeral homes that refused to take the bodies; and ashamed parents who told friends back home that their son died of “cancer.”

In the days following the election of Donald Trump, I told these stories to a friend. Like so many, and like me, she was despairing over what was to become of America. Racism, nationalism, paranoia, and rage were pre-existing realities, of course, but Trump’s win was a backlash — or “whitelash,” as CNN’s Van Jones put it — to the desire for progress, to the calls for justice by Black Lives Matter, the Occupy movement, feminist activists, the water protectors at Standing Rock. In an essay published a year ago in the New York Times, Wesley Morris wrote that America was “in the midst of a great cultural identity migration. Gender roles are merging. Races are being shed. In the last six years or so, but especially in 2015, we’ve been made to see how trans and bi and poly-ambi-omni we are.” Trump, he said, “is the pathogenic version of Obama, filling his supporters with hope based on a promise to rid the country of change.”

My friend is younger than me, a Millennial to my Gen-X. I wanted to offer something, to myself as much as to her. What I had was history.

For years, the official response to the AIDS catastrophe was stigma, derision and contempt. President Ronald Reagan ignored the deaths of thousands of Americans, including that of his old friend Rock Hudson, refusing to publicly utter the word “AIDS” until nearly the end of his presidency. His own communications director Pat Buchanan called the disease “nature’s revenge on gay men,” and Reverend Jerry Falwell said it was “the wrath of God upon homosexuals.” That was a violence and a trauma, too: how terribly and conveniently AIDS fit into the existing homophobic narrative that to be queer was to be diseased and deviant.

We didn’t have traditions to draw on. Many of us hadn’t met anyone else like us until we were adults. We had to imagine ourselves into being

Republican Senator Jesse Helms proposed a ban on travel to the United States by people who were HIV-positive in 1987; Bill Clinton signed it into law in 1993. It remained in place until 2009. In the intervening 22 years, there were no major international AIDS conferences held in America. HIV-positive foreigners couldn’t visit American relatives or friends. For those wishing to immigrate to the U.S. to join a spouse, waivers were available — but only for heterosexuals. Same-sex couples were excluded.

The activist movements that rose out of the 1980s and ’90s were confrontational, creative, and raucous. ACT UP and Queer Nation held die-ins and kiss-ins. The fire-eating Lesbian Avengers (their motto: “we recruit”) launched the first Dyke March. From HIV/AIDS, the cause expanded to hate crimes, employment discrimination, homophobia in popular culture, relationship recognition. Closeted public figures who didn’t stand with queer people were threatened with outing.

In Canada, activists protested Customs agents who routinely seized gay and lesbian books, magazines and videos at the border citing obscenity laws. They took on a neo-Nazi group called Heritage Front, which emerged in 1989 and hosted white power concerts, recruited disaffected white teenagers, and even infiltrated a mainstream conservative political party. One night, after a march to protest a skinhead rally, I went to catch a streetcar home and a courtly gay guy on his way to a bar in leather chaps and a cowboy moustache noticed I was leaving alone. He insisted on walking me to my stop, where he waited until I was safely onboard and then blew me a kiss goodbye. “We look out for each other, honey,” he said.

We didn’t have traditions to draw on: Our families of origin in far too many cases disowned us, and pop culture and media ignored or mocked us. Many of us hadn’t met anyone else like us until we were adults, believing as children and teenagers that we were all alone. We had to imagine ourselves, and our tools, into being. This time of fear and threat pushed us out of the closet, instigating a massive political and cultural revolution.

Networks of support dreamed up in living rooms and on dance floors evolved into hospices, high schools for queer teenagers, health clinics, film festivals, churches and synagogues, Pride marches, party circuits, and advocacy groups. Within the span of a few decades, institutions were built from scratch, funded from the proceeds of drag shows and club nights. Spontaneous vigils and rallies advertised by leaflets and phone trees grew into sophisticated political lobbying efforts that now have staff and offices. Ad hoc volunteer campaigns to pass out condoms in bars and parks evolved into safer sex education programs. New York and Chicago’s Black and Latinx underground drag balls created alternate family units and developed a uniquely queer art form. Gay and lesbian writers penned a canon of novels, poems and plays.

We’ve metabolized new technologies as though they’d always been there, doing what communities have always done, adapting available tools to share knowledge and survive as our conditions evolved

Lots of our efforts failed and rarely did we all — gay and lesbian, bi and trans, white folks and people of color, women and men, radicals and moderates, provocateurs and assimilationists — agree. And yet, collectively, we secured a slate of civil rights protections and anti-discrimination laws more rapidly than anyone would have thought possible.

AIDS doesn’t kill quite so often and so fast. Antiretroviral treatment has transformed the disease into a chronic condition for those who can afford it and have access to it; now the horizon is set on a vaccine. Like every other marginalized group has done, in the face of persecution and hate, we built what we needed to survive. The plague that killed so many of us didn’t destroy us. It created us.

I shared my history with my friend because I wanted to remind her that there are communities that have already survived, and are surviving, the end of the world. Progress has no final chapter, no concluding destination. Just more work.

Our infrastructure and institutions remain imperfect and unfinished. Within the community, the affluent, white, male, and the “straight-acting and straight-looking” dominate. The allure of respectability, of marriage rights and polite tolerance, has shut out those on the fringes, the gender non-conforming butches and queens. The mass shooting at the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando reminded us of the degree to which we are still hated; and, in the conversations that came in its aftermath, the specific vulnerability of those both queer and brown or black. “You know what the opposite of Latin Night at the Queer Club is? Another Day in Straight White America,” Justin Torres wrote in the Washington Post. “So when you walk into the club, if you’re lucky, it feels expansive. ‘Safe space’ is a cliché, overused and exhausted in our discourse, but the fact remains that a sense of safety transforms the body, transforms the spirit. So many of us walk through the world without it.”

This past Pride Day in Toronto, a group of activists from Black Lives Matter stopped the parade for 25 minutes to protest the overwhelming presence of police at the event; a number of floats from law enforcement agencies were welcomed in the parade. The queer community split in its response, many calling the action divisive and impolite: Our handsome prime minister was in the parade, waving to crowds in a pink shirt, and BLM had delayed him. What was lost in these attacks on the group was the history of the parade itself. Pride Day is a tribute to resistance and confrontation, a memorial to New York’s 1969 Stonewall Riots and, in Toronto, also to the massive protests that followed a series of police raids on gay bathhouses in 1983. It didn’t take long for memories to fade.

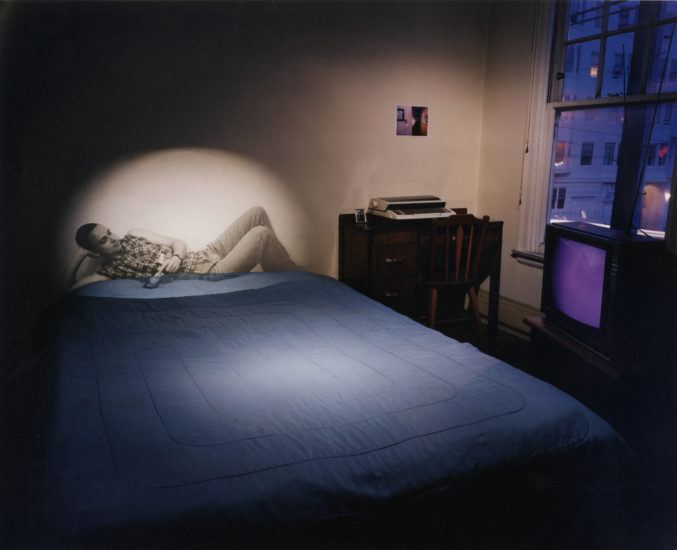

The queer world is no longer a small stretch of blocks scattered in isolated cities. A gay kid in farm country finds friends and boyfriends on Instagram, comes out because of Gay Straight Alliances and maybe even has a supportive mom who watches Ellen. A trans woman figures out who she is and how to find help by watching transition videos on YouTube, and calling hotlines in cities halfway across the country. Hooking up in bars and bathhouses has given way to GPS locating the nearest trick on Grindr.

We’ve metabolized these new technologies as though they’d always been there, doing what communities have always done, adapting and customizing the available tools to share knowledge and survive as our conditions evolved. And along the way the community has become bolder, less furtive, more connected and even, sometimes troublingly, more mainstream. Now it’s time to adapt and restructure again, to reckon with what we’ve achieved and lost, to direct our focus to those most vulnerable, like trans people who are being targeted in hate crimes, and LGBT people still facing violent persecution and imprisonment in countries likes Russia, Uganda, Jamaica. Some people say it feels like wartime again. And I think of the old queer protest slogan: An army of lovers cannot fail.