In a recent celebratory blog post from Waymo, Google’s self-driving-car offshoot, the company touts the success of its pilot program after a year of operation. “Over 400 riders with diverse transportation needs use Waymo every day, at any time, to ride all around the Phoenix area,” the PR team reports, before focusing in on a few of its driverless fleet’s “early riders.” One of these passengers, Barbara, is seeing her hometown like never before, according to the post: “Barbara says she’d do more knitting on her self-driving rides if she wasn’t so busy checking out the local sights with her husband Jim. Though she’s lived in the same neighborhood for 20 years, she missed a lot while she was focused on driving — even including a nearby park she never noticed before.”

Here, the driverless car is presented as a space of both relaxation and new productivity: Relieved from the burden of driving, Americans will have more choices about how they spend their time. Ironically enough, this evocation of escape and liberation is a recalibration of the rhetoric that helped establish driving as emblematic of the American way of life. Driving slotted easily into existing cultural values of freedom, individualism, and exploration. The road became a site of self-making as car manufacturers engaged in aggressive advertising campaigns to market driving as the ultimate expression of consumers’ individual preferences and identity. Physical mobility and the automobile were used as metaphors for upward social mobility and personal fulfillment.

Just as with the original car culture, enhanced mobility for some will come at the expense of embedded immobility for others

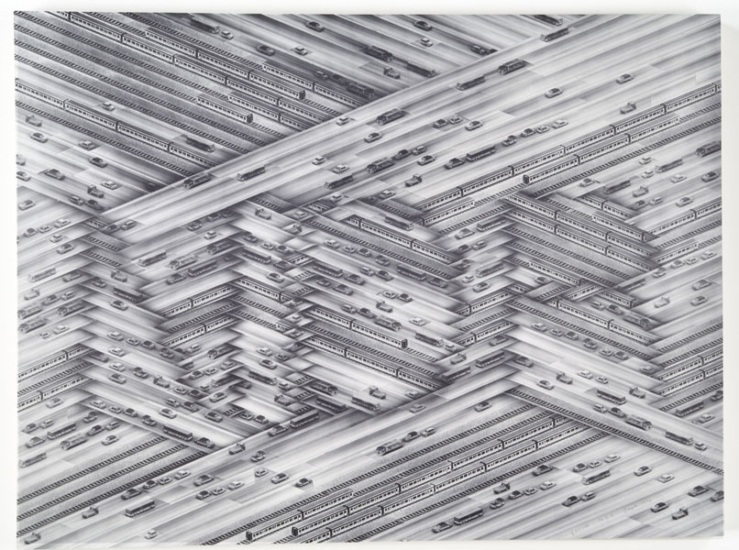

As car ownership became standard, it radically restructured American landscapes, infrastructure, employment, and routines, and contributed to suburbanization, longer commutes, and gridlock. It has become harder to conceive of taking the wheel as a pleasure in its own right, or romanticize it as an expression of individuality and autonomy. Auto marketing began to focus more on escape — think off-road SUVs climbing mountains or sports cars hitting the open highway. In Fast Cars, Clean Bodies, literary theorist Kristin Ross characterized the car as a “miraculous object” that can “offer solace from the conditions it has helped create.” And now, automakers are presenting us with an updated miracle that can free us from the drudgery and tedium that car culture has wrought: the autonomous vehicle.

The development of autonomous cars is enmeshed with contemporary debates about emerging technologies, such as the future of artificial intelligence, the automation of labor, government regulation of technology, and the ever-increasing trust in computation as the wellspring of truth and safety. Nearly every major technology company (Google, Amazon, Uber, Lyft, Intel) and almost all major automotive manufacturers (Tesla, GM, Ford, Toyota, BMW, Mercedes, VW, Audi, Volvo, Nissan and Honda) are competing to build them. Given these stakes, it’s important to ask not only whether driverless cars can work but how the technology is being domesticated. What political work is being performed to make the autonomous future seem ordinary and inevitable, a natural next step in making people’s lives more convenient?

Proponents of the driverless car have tapped into the legacy associations of autos with liberty and escapism and inverted them. For instance, John Zimmer, the co-founder of Lyft, has argued that its model for autonomous vehicle services will give us freedom from cars, liberating us from the burden of having to own an expensive, money-sucking vehicle. An Ad Age article proposes that autonomous vehicles will free Americans from their tedious commutes, turning the automobile into a space of even greater leisure, entertainment, and convenience. As passengers are ferried around by an automated chauffeur, they will have the luxury to focus on interior screens and displays.

At the same time, media coverage of autonomous vehicles has emphasized how autonomous cars will extend freedom of mobility to the elderly, the disabled, the poor, and otherwise neglected groups. In an op-ed written in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette near the end of his presidency, Barack Obama made a similar claim. In 2016, Waymo widely publicized the first unaccompanied journey taken in its autonomous car by a legally blind man. Meanwhile, other groups — individuals who are barred from obtaining a driver’s license such as undocumented immigrants or recipients of DUIs — are overlooked: Perhaps that’s because these sorts of individuals might trouble the narrative about who deserves freedom and who should be allowed to escape. Just as with the original car culture, enhanced mobility for some will come at the expense of embedded immobility for others.

More than anything else, autonomous vehicles, we’re promised, will liberate us from bad drivers. Driverless cars will keep us safe. They will be more reliable than unpredictable and dangerous humans. “Computers don’t get drunk,” says Stephen Zoepf, the executive director of the Center for Automotive Research at Stanford. “There are a sweeping group of accidents that will go away,” he told Stanford News.

Is the purpose of human oversight to ensure safety or to provide a scapegoat?

Zoepf and other driverless car advocates hold (reckless, irresponsible) humans responsible for automotive accidents. Anthropologist S. Lochlann Jain has argued, however, that the figure of the “negligent driver,” was created by lawyers representing automakers to absorb blame for vehicular deaths. In the courtroom, Jain notes, auto accidents are framed as individuated occurrences, attributable to the specificities of unique drivers and case-by-case situations rather than the result of potential structural problems at the level of product design. Given the frequency of automobile accidents — about 30,000 fatal collisions occur in the U.S. each year — human drivers are framed as always already negligent and irresponsible. Automated driving technology is presented as the necessary, inevitable solution.

But the self-driving car is not nearly as autonomous as it sounds. It relies on a range of environmental, technical, and social infrastructures: satellite signals, sensor feedback, energy grids, fuel stations, legal frameworks, and neural networks. The rhetoric of autonomy and automation, often oversold by Silicon Valley developers seeking funding and fame, whisks these arrangements out of view, masking the infrastructural and political work required to make them run. Testing autonomous vehicles, for instance, requires new legislation to address issues of safety and liability. Politicians in Arizona, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, in particular, have embraced self-driving cars and introduced preferential legislation that favors tech developers and carmakers, granting them access to public roads without the burden of permitting and reporting requirements. Detroit and Pittsburgh, former capitals of the automotive and manufacturing industries, are especially eager to regain their foothold in the wake of declining domestic auto production. Arizona governor Doug Ducey courted autonomous vehicle developers and in 2016, according to journalist Jacob Silverman, supported the launch of a driverless car pilot program before first informing the public.

Elaine Herzberg, the first pedestrian killed by an autonomous vehicle, was struck by one of Uber’s self-driving cars in Ducey’s home state of Arizona in May 2018. According to a preliminary report by NTSB investigators, the car’s sensors had detected Herzberg, but because she was walking her bike across a crosswalk, the software first “classified her as an unknown object, then as a vehicle, and finally as a pedestrian.” Media portrayals of the event, however, attributed the cause of death to the human safety inspector’s failure to notice Herzberg and override the automated system. Similarly, this recent article from Axios concludes that “people cause most California autonomous vehicle accidents.” This reversion to blaming the human driver not only protects the machine, it also deflects blame from its programmers.

Her death, among other autonomous vehicle fatalities, casts doubt on the assumption that robot drivers are inherently safer than their human counterparts. Driverless vehicles’ purpose is overcoming human error, yet they rely on human operators to monitor and supervise them. How can these systems protect us from “human recklessness” if they’re designed by humans and draw upon human-coded data to mimic human driver behavior? Is the purpose of human oversight to ensure safety or to provide a scapegoat? In the eagerness to embrace autonomous vehicles as an escape from inconvenience, are we dodging ethics?

In conversations about the ethics of autonomous vehicles, scholars and journalists have repeatedly raised the trolley problem as the essential hurdle driverless cars must clear before they can be widely deployed. (See, for example, this 2013 essay in the Atlantic, this 2015 article in the Guardian, this 2015 Stanford Business School case study, this 2015 piece in MIT’s Technology Review.) Originally proposed by philosopher Philippa Foot in the 1960s, it asks whether a bystander who observes a runaway trolley hurtling toward five people should pull a lever to direct it onto another track where it will kill one person instead. Built in to the question is a certain fatalism: No matter the choice, it is assumed that someone must die.

The fantasy of autonomous vehicles, as with conventional autos before them, is that gains in efficiency and convenience might outweigh lingering injustices

Autonomous vehicles will likewise encounter scenarios where they must decide between swerving to avoid pedestrians or putting their own passengers at risk. Researchers at MIT have approached the issue with the same machine-learning principles that drive autonomous vehicles’ computer vision, launching a project called the Moral Machine to gather “human opinion on how machines should make decisions when faced with moral dilemmas.” The 30-million-plus survey responses they have received will be used to train AI systems to help them learn and imitate what humans consider to be ethical behavior, just as human perception of road signs have trained the detection algorithms.

But the trolley problem maps poorly onto how ethical conundrums actually occur in daily life. As philosopher Johannes Himmelreich has pointed out, the outsize focus on the trolley problem falsely portrays ethics as a choice between two clearly delineated options with known consequences, thereby obscuring a range of other important questions, including whether it is ethical to test self-driving cars on public streets without the knowledge and consent of pedestrians and passerby. Given the data retention and tracking of these vehicles (and the data harvesting practices of the companies who are racing to build autonomous vehicles), how can we curb the risk to individuals’ privacy? How should public safety and regulation be balanced against innovation? How many accidental deaths are acceptable in the short term in exchange for the promise of fewer car crashes in the long term? How do driverless car efforts divert attention and funding from other public goods, such as mass transit? In what ways will these technologies re-entrench economic inequality and social injustice?

The focus on the trolley problem demonstrates how the developers of driverless car have translated ethics into an engineering problem. Mimicking the structure of the conditional if-then statements that are encoded into algorithms, the trolley problem distills machine ethics into an unlikely event that imposes a binary choice between two tragic alternatives, rather than the thornier and more complex quandaries that emerge at the societal or systemic level.

But there is no easy escape from these ethical questions. As sociologist Ruha Benjamin has pointed out, “our collective imaginations tend to shrink when confronted with entrenched inequality and injustice, when what we need is just as much investment and innovation in our social reality as we pour in to transforming our material lives.”

As much as the negative social and environmental effects that the automotive age has wrought — pollution, traffic, urban sprawl, unwalkable cities, poor public transportation systems, the obesity epidemic — have been naturalized as definitive parts of American culture and life, their detrimental effects remain inescapable. Rather than considering the impact of the current transportation system that prioritizes individual journeys, the driverless car extends and entrenches this model. The fantasy of autonomous vehicles, as with conventional autos before them, is that gains in efficiency and convenience might outweigh lingering injustices.

If we consider how the self-driving car slots not only into the existing physical infrastructure (with its embedded biases) but also social infrastructures that valorize independence, individuality, and mobility, we begin to see the driverless car less as a radical future and more a modest extension of our current reality — despite Google’s characterization of the autonomous vehicle as a “moonshot technology.” If we passively accept the driverless car as a predestined future, we’ll be taking our hands off the wheel and letting ourselves be driven back to where we started from.