The second annual CyFyAfrica 2019 — the Conference on Technology, Innovation, and Society — took place in Tangier, Morocco, in June. It was a vibrant, diverse and dynamic gathering attended by various policymakers, UN delegates, ministers, governments, diplomats, media, tech company representatives, and academics from over 65 nations, mostly African and Asian countries. The conference’s central aim, stated unapologetically, was to bring forth the continent’s voices in the global discourse. The president of Observer Research Foundation (one of the co-hosts of the conference) in their opening message emphasized that the voices of Africa’s youth need to be put front and center as the continent increasingly comes to rely on technology to address its social, educational, health, economic, and financial issues. The conference was intended in part to provide a platform for those young people, and they were afforded that opportunity, along with many Western scholars from various universities and tech developers from industrial and commercial sectors.

Tech advocates typically offer rationales for attempting to digitize every aspect of life, at any cost

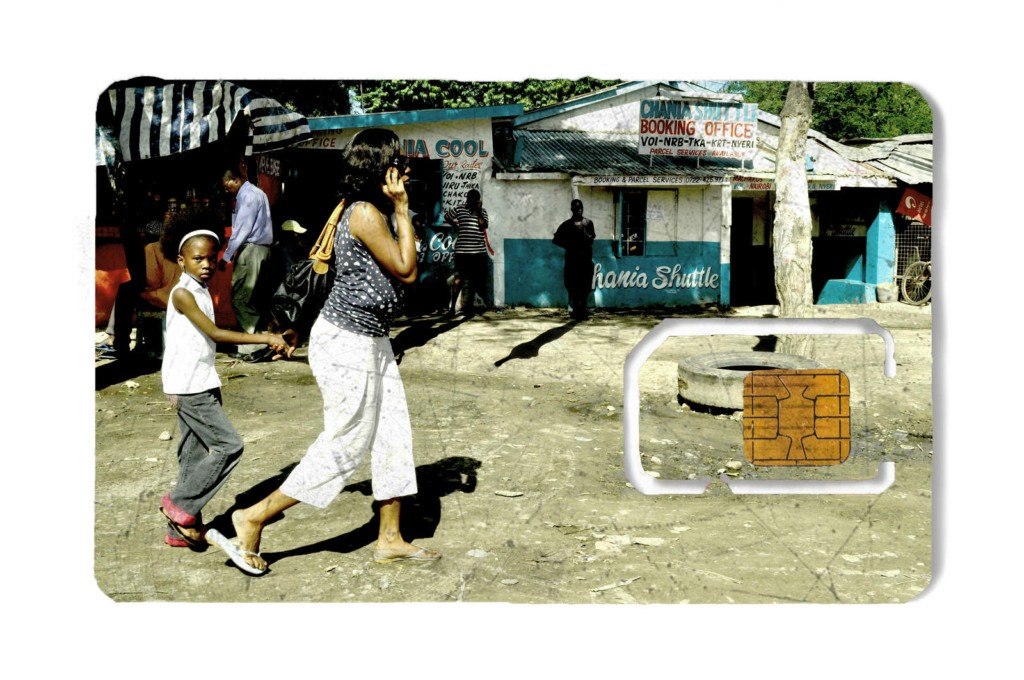

The African equivalent of Silicon Valley’s tech startups can be found in any corner of the continent — “Sheba Valley” in Addis Ababa, “Yabacon Valley” in Lagos, and “Silicon Savannah” in Nairobi, to name a few — and are pursuing “cutting-edge innovations” in such sectors as banking, finance, heath care, and education. The continent does stand to benefit from these various technological and artificial-intelligence developments: Ethiopian farmers, for example, can use crowdsourced data to forecast and yield better crops. And data can help improve services within education and the health care sector, as this World Heath Organization bulletin details. Data can help bridge the huge inequalities that plague every social, political, and economical sphere. By revealing pervasive gender disparities in key positions, for instance, data can help bring the disparities to the fore and, further, support social and structural reforms.

Having said that, however, this is not what I want to discuss here. There are already countless die-hard technology worshipers both within and outside the continent who are only too happy to blindly adopt anything “AI,” “smart,” or “data-driven” without a second thought of the possible unintended consequences. Wherever the topic of technological innovation arises, what we typically find is tech advocates offering rationales for attempting to digitize every aspect of life, often at any cost. If the views put forward by many of the participants at CyFyAfrica 2019 are anything to go by, we already have plenty of such tech evangelists in (and outside) Africa, blindly accepting ethically suspect and dangerous practices and applications under the banner of “innovative,” “disruptive,” and “game changing” with little, if any, criticism or skepticism. Look no further than the speaker lineups and the topics of discussion of some of the biggest AI or machine learning conferences taking place throughout the continent: Ethical considerations, data privacy, or AI’s unintended consequences hardly ever feature in these events. The upcoming Deep Learning Indaba conference in Nairobi is a typical example.

Given that we have enough tech worshipers holding the technological future of the continent in their hands, it is important to point out the cautions that need to be taken and the lessons that need to be learned from other parts of the world. Africa need not go through its own disastrous cautionary tales to discover the dark side of digitization and technologization of every aspect of life.

Data and AI seem to provide quick solutions to complex social problems. And this is exactly where problems arise. Around the world, AI technologies are gradually being integrated into decision-making processes in such areas as insurance, mobile banking, health care and education services. And from all around the African continent, various startups are emerging — e.g. Printivo in Nigeria, Mydawa in Kenya — with the aim of developing the next “cutting edge” app, tool, or system. They collect as much data as possible to analyze, infer and deduce the various behaviors and habits of “users.”

But in the race to build the latest hiring app or state-of-the-art mobile banking system, startups and companies lose sight of the people behind each data point. “Data” is treated as something that is up for grabs, something that uncontestedly belongs to tech companies and governments, completely erasing individuals. This makes it easy to “manipulate behavior” or “nudge” people, often toward profitable outcomes for the companies and not the individuals. As “nudging” mechanisms become the norm for “correcting” individual’s behavior, whether its eating habits or exercising routines, the private-sector engineers developing automated systems are bestowed with the power to decide what “correct” is. In the process, individuals that do not fit stereotypical images of what, for example, a “fit body” or “good eating habits” are end up being punished and pushed further to the margin. The rights of the individual, the long-term social impacts of these systems, and their consequences, intended or unintended, on the most vulnerable are pushed aside — if they ever enter the discussion at all.

AI, like big data, is a buzzword that gets thrown around carelessly; what it refers to is notoriously contested across various disciplines, and the term is impossible to define conclusively. It can refer to anything from highly overhyped deceitful robots to Facebook’s machine-learning algorithms that dictate what you see on your News Feed to your “smart” fridge. Both researchers in the field and reporters in the media contribute to overhyping and exaggerating AI’s capacities, often attributing it with god-like power. But as leading AI scholars such as Melanie Mitchell have emphasized, we are far from “superintelligence.” Similarly, Jeff Bigham notes that in many widely discussed “autonomous” systems — be it robots or speech-recognition algorithms — much of the work is done by humans, often for little pay.

Exaggeration of the capabilities of AI systems diverts attention from the real dangers they pose, which are much more invisible, nuanced, and gradual than anything like “killer robots.” AI tools are often presented as objective and value-free. In fact, some automated systems used for hiring and policing are put forward with the explicit claim that these tools eliminate human bias. Automated systems, after all, apply the same rules to everybody. But this is one of the single-most erroneous and harmful misconceptions about automated systems. As the Harvard mathematician Cathy O’Neil explains in Weapons of Math Destruction, “algorithms are opinions embedded in code.” Under the guise of “AI” and “data-driven,” systems are presented as politically neutral, but because of the inherently political nature of the way data is construed, collected, and used to produce certain outcomes (that align with those controlling and analyzing data), these systems alter the social fabric, reinforce societal stereotypes, and further disadvantage those already at the bottom of the social hierarchy.

“Data” is treated as something that is up for grabs

AI is a tool that we create, control, and are responsible for, and like any other tool, it embeds and reflects our inconsistencies, limitations, biases, and political and emotional desires. How we see the world and how we choose to represent it is reflected in the algorithmic models of the world that we build. Therefore who builds the systems and selects the sorts and sources of data used will deeply affect the influence they may have. The results that AI systems produce reflect socially and culturally held stereotypes, not objective truths.

The use of technology within the social sphere often, intentionally or accidentally, focuses on punitive practices, whether it is to predict who will commit the next crime or who would fail to pay their mortgage. Constructive and rehabilitative questions such as why people commit crimes in the first place or what can be done to rehabilitate and support those that have come out of prison are almost never asked. Technological developments built and applied with the aim of bringing “security” and “order” often aim to punish and not rehabilitate. Furthermore, such technologies necessarily bring cruel, discriminatory, and inhumane practices to some. The cruel treatment of the Uighurs in China and the unfair disadvantaging of the poor are examples in this regard. Similarly, as cities like Johannesburg and Kampala introduce the use of facial recognition technology, the unfair discrimination and over-policing of minority groups is inevitable.

Whether explicitly acknowledged or not, the central aim of commercial companies developing AI is not to rectify bias generally but to infer the weaknesses and deficiencies of individual “users,” as if people existed only as objects to be manipulated. These firms take it for granted that such “data” automatically belongs to them if they are able to grab it. The discourse around “data mining” and a “data-rich continent” — common language within Africa’s tech scene — shows the extent to which the individual behind each data point remains inconsequential from their perspective.

This discourse of “mining” people for data is reminiscent of the colonizer attitude that declares humans as raw material free for the taking. As we hand decision-making regarding social issues over to automated systems developed by profit-driven corporations, not only are we allowing our social concerns to be dictated by corporate incentives (profit), but we are also handing over complex moral questions to the corporate world.

Behavior-based “personalization” — in other words, the extraction, simplification, and instrumentalization of human experience for capitalist ends, which Shoshana Zuboff details in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism — may seem banal compared with the science fiction threats sometimes associated with AI. However, it is the basis by which people are stripped of their autonomy and are treated as mere raw data for processing. The inferences that algorithmic models of behavior make do not reflect a neutral state of the world or offer any in-depth causal explanations but instead reinscribe strongly held social and historical injustices.

Technology in general is never either neutral or objective; it is a mirror that reflects societal bias, unfairness, and injustice. For example, during the conference, a UN delegate addressed work that is being developed to combat online counterterrorism but disappointingly focused explicitly on Islamic groups, portraying an unrealistic and harmful image of online terrorism: over the past nine years, there have been 350 white extremist terrorism attacks in Europe, Australia, and North America; one third of all such attacks in this time period in the U.S. are due to white extremism. This illustrates the worrying point that stereotypically held views drive what is perceived as a problem and the types of technology we develop in response. We then hold what we find through the looking glass of technology as evidence of our biased intuitions and further reinforce stereotypes.

Some key global players in technology — for example, Microsoft and Google’s DeepMind from the industry sector; and Harvard and MIT from the academic sphere — have begun to develop ethics boards and ethics curricula in acknowledgment of the possible catastrophic consequences of AI on society. Various approaches and directions have been advanced by various stakeholders to pursue fair and ethical AI, and this multiplicity of perspectives is not a weakness but a strength: It is necessary for yielding a range of remedies to address the various ethical, social, and economical issues AI generates in different contexts and cultures. But too often, attempts to draft the latest “ethics framework” or the “best guideline to ethical AI” center the status quo as the standard and imply that the solution put forward is the only necessary one. Insisting on a single one-size-fits-all ethical framework for AI, as one of the conference’s academic speakers advised, is not only unattainable but would also worsen the problems it is meant to address in those contexts it wasn’t equipped to anticipate.

“Mining” people for data is reminiscent of the colonizer attitude that declares humans as raw material

Society’s most vulnerable are disproportionally affected by the digitization of various services. Yet many of the ethical principles applied to AI are firmly utilitarian. What they care about is “the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people,” which by definition means that solutions that center minorities are never sought. Even when unfairness and discrimination in algorithmic decision-making processes are brought to the fore — for instance, upon discovering that women have been systematically excluded from entering the tech industry, minorities forced into inhumane treatment, and systematic biases have been embedded in predictive policing systems, to mention a few — the “solutions” sought hardly center those on the margin that are disproportionally affected: Mitigating proposals devised by corporate and academic ethics boards are often developed without the consultation and involvement of the people that are affected. But their voice needs to be prioritized at every step of the way, including in the designing, developing, and implementing of any technology, as well as in policymaking. This requires actually consulting and involving vulnerable groups of society, which might (at least as far as the West’s Silicon Valley is concerned) seem beneath the “all-knowing” engineers who seek to unilaterally provide a “technical fix” for any complex social problem.

As Africa grapples with catching up with the latest technological developments, it must also protect the continent’s most vulnerable people from the consequential harm that technology can cause. Protecting and respecting the rights, freedoms and privacy of the very youth that the leaders of the CyFyAfrica conference want to put at the front and center should be prioritized. This can only happen with guidelines and safeguards for individual rights and freedom in place in a manner that accounts for local values, contexts and ways of life, as well as through the inclusion of critical voices as an important part of the tech narrative. In fairness, CyFyAfrica did allow for some critical voices in some of the panels. However, the minor critical voices were buried under the overwhelming tech enthusiasts.

Following the conference, speakers were given the opportunity to share their views and research for publication in a semi-academic journal run by the Observer Research Foundation. Like other speakers at the conference, I was encouraged to submit my observations and reflections. However, when I submitted a version of this essay, it was deemed too critical by the editorial board and therefore unsuitable for publication. Ironically, the platform that claims to give voice to the youth of Africa only does so when that voice aligns with the narratives and motives of the powerful tech companies, policy makers, and governments.

The question of technologization and digitalization of the continent is a question of what kind of society we want to live in. African youth solving their own problems means deciding what we want to amplify and show the rest of the world. It also means not importing the latest state-of-the-art machine learning systems or any other AI tools without questioning what the underlying purpose is, who benefits, and who might be disadvantaged by the implementation of such tools.

Moreover, African youth leading the AI space means creating programs and databases that serve various local communities and not blindly importing Western AI systems founded upon individualistic and capitalist drives. It also means scrutinizing the systems we ourselves develop and setting ethical standards that serve specific purposes instead of accepting Western perspectives as the standard. In a continent where much of the narrative is hindered by negative images such as migration, drought, and poverty, using AI to solve our problems ourselves means using AI in a way we want, to understand who we are and how we want to be understood and perceived: a continent where community values triumph and nobody is left behind.