There is the language adults use with each other and the language they use with children, which, in linguistics, is known as “child-directed” or “caretaker” speech. Caretaker speech obeys a separate grammar from adult speech, with diminutive inflections and suffixes. It might have doggy-woggy in place of dog, or hammy instead of hamster. The trick is in the context. To use caretaker speech with kids shows adeptness. To use it with other adults blows a fuse in the social code, humiliating your interlocutor and making yourself seem unhinged. “What a nice doggy-woggy” is something I could say to the young man who rides my subway line with his giant gray pitbull on weekday afternoons, if I wished to be punched in the face.

All year, riding to meetings and home from drinks, I have been obsessed with figuring out why I hate the Seamless ads in the New York City subway. “Welcome to New York,” one reads. “The role of your mom will be played by us.” That’s quite a claim. Is Seamless going to tell me it’s not too late to go to law school? A second ad suggests that when I think I’m “angry” I might just be “hungry.” A third ad derides suburbanites, who are “dead” because they live in “Westchester.” The personality is half mom, half teenager: “cool babysitter.” Seamless will let me stay up late, eat Frosted Flakes for dinner, and watch an R-rated movie.

Every time I get an email from Seamless I brace myself for the contents, which include phrases like “deliciousness is in the works” and suggestions that I am ordering takeout because I am at a “roof party” or participating in a “fight club.” Seamless allows that I may even be immersed in an “important meeting,” a meeting so important that I am secretly interrupting it to customize a personal pizza. I picture a cool babysitter, Skylar, with his jean vest, telling me as he microwaves a pop-tart that “deliciousness is in the works,” his tone just grazing the surface of mockery, because I am a loser who must be babysat.

Yelp’s identity is anchored by its pull-to-refresh icon, a little hamster in a rocket ship. Who is the person who enjoys this?

All over the city Seamless belittles me. “Let someone who can spell baba ghanoush make it,” says a billboard in Tribeca. There was a time when you moved to New York to become worldly, but Seamless doesn’t think Tribeca residents can spell what they eat, nor that they can be bothered learning how. The vision of the Seamless cosmopolitan is a guy typing random consonants into his iPhone until an immigrant comes to his door with an appetizer platter.

If Seamless doesn’t believe I can spell what I eat, Yelp doesn’t think I know where to get it, or when I want it. Logging on at 4 p.m. to find a liquor store, I find the app suggesting an afternoon snack. Have I eaten? Maybe Yelp is my mother.

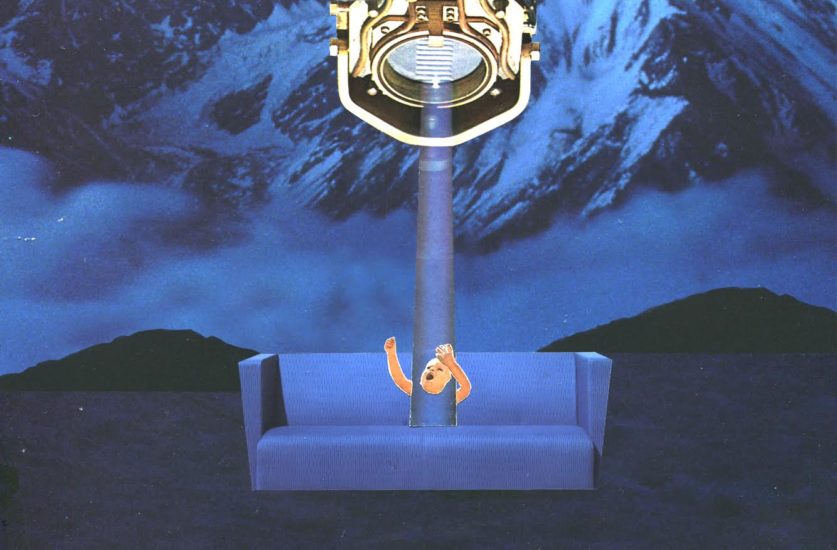

Yelp’s identity is anchored by its pull-to-refresh icon, a little hamster in a rocket ship. This hamster has a name. It’s Hammy. While you are refreshing a page of search results, Hammy does a side-to-side dance, and then the rocket blasts off toward the top of the screen. (Android users more likely encounter Hammy not in pulling to refresh, but in the nav drawer.) Who is the person who enjoys this? Yelp is for adults with disposable income and a high degree of mobility, two things that usually — should — preclude friendships with stuffed animals.

Yelp provides reviews; when you open it, reviews confront you. Venmo provides money transfers, yet when you open it, you see other people’s unrelated money transfers. Venmo is the steps of the high school at 2 p.m., when everyone’s talking about who went out with whom. Did you hear that Kaitlin was with Mitchell last night? Yeah, and I heard they had two beers. When you type “beer” into Venmo, a drop-down menu displays the beer emoji. Type “horse,” see a horse. “Pig,” pig. “House,” house. My surprise that no one is insulted by this is quickly overtaken by surprise that Venmo is condoning alcohol consumption among kindergarteners, the only group in America who is routinely asked, with educational toys like Leapfrog, to match short words with pictures.

Because I can’t object in any meaningful way to the tone of these apps, which have monopolies on their services and which I use constantly, many times a day, my frustration misdirects, as frustration will, onto related but non-complicit adversaries. I landed in New York one night last winter, having flown in from Las Vegas, and a song from the Disney movie Frozen began playing in the cabin. The jetway took a long time to get connected; we were stuck; the speakers were very loud. The song begins:

We used to be best buddies

And now we’re not

I wish you would tell me why!

Do you wanna build a snowman?

There were very few children in the cabin. Across the aisle, a woman from New Jersey, wearing a deep tan and a black loose-knit sweater with gold jewelry, made eye contact with me. We sensed kindred, judgmental spirits. “The fuck is playing in my eeeeyahs?” she said.

“I know,” I said.

“The fuck,” she said.

I said maybe we should scream, so we screamed up the cabin. Turn the fucking music off! Build a fucking snowman somewhere else, this is New York City. And so on. We were really getting into it. Other passengers, emboldened, started to clap. I was moved. I now understood how Lenin felt approaching the Finland Station. Only later, walking out to the taxi stand, did I realize how I’d embarrassed myself. In order to protest being treated like a child, I’d thrown a temper tantrum.

When I got home, I wrote a complaint letter to Delta describing my frustration with the music while conveniently omitting that I myself had caused a worse disturbance. A letter seemed a more adult response. A week later, I received the following reply:

Thanks for sharing your flight experience to New York with us. I’m truly sorry to learn about your frustration with the music played while the plane was landing. I know that this troubled you a lot.

I recognized this tone. A school social worker addresses a “troubled child.”

We’re in the middle of a decade of post-dignity design, whose dogma is cuteness. One explanation would be geopolitical: when the perception of instability is elevated, we seek the safety of naptime aesthetics. Reading about the mania for adult coloring books, a proof so absurd that the New York Times has published four articles about it, you find that some colorers can’t get to sleep without filling in a mandala on paper, while others need “a special time when we’re not allowed to talk about school or kids.” Adulthood stretches pointlessly out ahead of us, the planet is melting off its axis, you will never have a retirement account. Here’s a hamster. That would be the demand-side argument, where the consumer’s fears set the marketer’s tone. That would also be false. The real power lies on the supply side: Hammy wasn’t born in our fantasies, but in a Silicon Valley office.

Adulthood stretches pointlessly out ahead of us, the planet is melting off its axis, you will never have a retirement account. Here’s a hamster

In her essay “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde,” Sianne Ngai, a professor at Stanford, theorizes cuteness as an “aesthetic of powerlessness.” In the face of the overwhelming question — “What’s it for?” — a strain of avant-garde art responds by playing up its inutility, she argues. It magnifies its impotence until “it begins to look silly.” Ngai’s concerns, admittedly, weigh heavier than any app or Disney-movie soundtrack: she deals in her essay with Beckett, Adorno, and Stein. But one of her key observations, that we tend to read cuteness as evidence of “restricted agency” rather than as evidence of concealed and significant power, proves useful when looking at the visual language of apps.

What unites Yelp, Seamless, and Venmo is, in part, their desire to monopolize particular spheres of adult life (“spaces,” in Valleyspeak). They also offer services that diminish the user’s autonomy in a way that — from a certain low angle, in a certain light — reads as patronizing when we’re supposed to be the patrons. We cannot find food on our own, or choose a restaurant, or settle a tiny debt. Where that dependency feels unseemly in the context of independent adult life, it feels appropriate if the user’s position remains childlike, and the childlikeness makes sense when you consider that Yelp depends on us to write reviews, and therefore must, like a fun mom, make chores feel fun too.

A playful interface carries a secondary benefit, because the public’s perception of the goodness or evil of a Silicon Valley company often hinges on the design of the company’s apps. Yelp, like Google, makes money by collecting consumer data and reselling it to advertisers. Four years ago, Yelp CEO and co-founder Jeremy Stoppelman testified in Washington against Google, arguing that the search engine was a monopoly that favored Google Local products, excluded competitor results, and co-opted content from Yelp. “Is a consumer (or a small business, for that matter) well served when Google artificially promotes its own properties regardless of merit?” asked Stoppelman. “This has nothing to do with helping consumers get to the best information; it has everything to do with generating more revenue.” Last year, Yelp reported a half billion dollars of revenue, 83 percent derived from local advertising. Yelp wields tremendous power over the owners of small businesses — some of whom have accused the company of gaming the ratings and reviews system to favor those who advertise, pressuring those who don’t into doing so — and knows more about consumer habits and travel patterns than we might wish a publicly traded corporation to know. A 2015 Fortune article called “Trustworthy Alternatives to Yelp” would have been better titled “Alternatives to Yelp. Just Kidding,” since none of the competitor apps listed were popular, recognizable, or very good, and two have since gone out of business. Yelp doesn’t have to look any more lovable than Google, but it does — and it is. Who would hate Yelp?

By contrast, consider the design of the most hated app in Silicon Valley. In 2012, Uber stood alone. Black, sinister, efficient. The logo like devil’s horns. The invisible umlaut. In the place of cuteness, Uber offered a fantasy of minimalist sadism, with the user holding the whip. When Lyft announced itself as a competitor to Uber, it was with furry hot pink mustaches, stuck on the front of each car. The logo too was pink and pneumatic, accompanied by a single balloon, and an early tagline was, nonsensically, “Get in a mustache state of mind.” Passengers were encouraged to fist-bump each other, like two or more Skylars headed to spend their babysitting money. In December 2014, two days after publishing an op-ed accurately titled “We Can’t Trust Uber,” the New York Times ran a chiding analysis of Lyft’s branding with the headline “Is Lyft Too Cute To Fight Uber?” Lyft dropped the plush mustaches, turning them into discreet windshield stickers, but kept the hot pink and the warm fuzzies, with later taglines like “Driving You Happy.”

Uber wishes to be in the self-driving car business one day, and its indifference to human drivers has provided good fodder for journalists looking to expose the anti-human ethos of the Valley. After a year of bad press, Uber unveiled a redesign this past February: colorful but not loud, geometric but not slick, “midcentury modern.” Travis Kalanick, the founder and CEO of Uber and an engineer by training, insisted on handling the rebrand himself, working with designers in a “space” he called the “War Room,” according to Wired. Kalanick wanted to show that under the bravado he was just a big softie:

During Uber’s early years, Kalanick came across as a bellicose bro, a rebel-hero always angling for a confrontation — with regulators, the taxi industry, and competitors. Reflecting on this, Kalanick says it was all a misrepresentation by the media. When you don’t really know who you are, he says, it’s easy to be miscast — as a company, or as a person. For Kalanick, who turns 40 this year and has gained a few more shades of silver in his spiky, salt-and-pepper hair, this rebrand has been an act of self-exploration.

Continuing to explore himself this past April, Kalanick sat down with his father, Donald Kalanick, for a “candid conversation” that was edited into a seven-minute video — “Uber CEO Travis Kalanick and His Dad Open Up About Life, Love, and Dropping Out of School” — for the Huffington Post’s parent-child interview series, Talk To Me. The son asks his dad if he ever thought his app idea was stupid. The dad reassures his son that he thought it was “fantastic.” That week, Bloomberg reported that Lyft was “successfully luring customers and drivers in a costly land grab with its bigger rival,” having raised a billion dollars and defied expectations to gain swiftly on Uber in American cities. Do you think that when self-driving cars achieve ubiquity, the VCs behind Lyft will sit that revolution out? Don’t let the pink mustache fool you. It may be hiding a smirk.

There is no better example of cuteness applied in the service of power-concealment than Pokémon Go, which is a large data-collection and surveillance network devised by the former Google Earth engineers at Niantic and then candy-coated with Nintendo IP. The privacy policy — unlocking the door to your profile information, geodata, camera, and in some cases emails — is so disturbing that it has set off alarms even in the tech world. As I was writing this, a friend told me that the management of her billion-dollar startup instructed all employees not to download Pokémon using their company email address. We do not understand how the technology will be applied when the time comes to monetize it. I would bet that Pokémon and similar games will ultimately allow corporations to collect real-time photographic data on almost anything they want, anywhere in the world. An investment bank wants to put money into McDonald’s, but the rumor is that third-quarter earnings will be weak. Ten thousand Pikachus appear in ten thousand restaurants, luring customers in to serve as unwitting spies on the success of the entire chain in real time. The privacy agreement allows Niantic Labs to snap a photo of what the user thinks is a Pikachu but Niantic knows is $500,000 worth of market research. Now imagine the client is a police chief, or the Department of Homeland Security.

When adults act like kids, you can take their money like candy

Earlier this month in Missouri, four teenagers lured Pokémon hunters into a “secluded area” and instead of providing them with Pikachus, robbed them. They understood something simple: When adults act like kids, you can take their money like candy. In interviews, the CEO of Niantic uses the grown-up language of economics to discuss the app’s possible revenue streams — “sponsored locations,” “cost-per-visit” — but child-directed language to discuss the experience of using it. He has said he wants his users “to see the world with new eyes.”

Many apparently do. In a Sunday Review piece for the Times, Amy Butcher, a professor at Ohio Wesleyan, writes approvingly of using Pokémon with her boyfriend. Initially skeptical, she overcame her resistance and found her community had done the same. “The neighborhood buzzed with people out exploring,” she writes. “A local Creole restaurant became a Poké Stop, unlocked only from within, and so people clustered within the lobby, waiting for tables or ordering takeout.” (The latter group, on Seamless, not learning how to spell étouffée.) The game returns her to nature, as she and her boyfriend visit a local park “in pursuit of a water creature,” and finally they go swimming, “forgetting altogether what it was that brought us there.” Indeed.

Butcher defends her argument preemptively against Pokémon haters. “It seems far from terrible to see a father and son racing down suburban sidewalks [in pursuit of Pokémon],” she writes. But this is a sleight of hand: You can share in the experience of Pokémon or you can object to a father and son racing down suburban sidewalks. The comedy writer Megan Amram took a similar tack. “Do whatever you want,” she tweeted, “as long as it doesn’t hurt anyone. Play a children’s game on ur phone. Take a selfie. Be gay. Who the hell cares.” Structurally, we are put in a position where we either enjoy hunting for water creatures or we are the sort of person who would care that someone is gay.

And in fact it’s broader than that. We are put in a position where we either embody the forces of repression or we enjoy a Silicon Valley product. What a convenient little elision for the Valley, the seat of real power. They’re not the repressive force; opposing them is. All they want is to let us be as free as when we were kids.

In Lipstick Traces, an alternative map of 20th-century cultural history, Greil Marcus excerpts the 1977 shareholder report by Warner Communications, which noted that “entertainment has become a necessity.” This was an accurate statement, one that Marcus identified as a warning. Yet neither he nor the Warner executives could have prophesied its corollary, that we would become unable or unwilling to meet our needs without also being entertained. When we learn to expect playfulness from mundane tasks like ordering food or finding a pharmacy, or when we won’t go swimming without a Pokéchaperone, the result is a state of unsuspecting childlikeness, while adults wait in the woods to take their profits. My frustration with these apps only tells me I’m becoming the child they’re informing me I am. That’s the scary part, a dignity so fragile that a cartoon hamster breaks it.