Tiona Nekkia McClodden – Affixing Ceremony: Four Movements for Essex, Movement I, 2015 (handwritten text by artist).

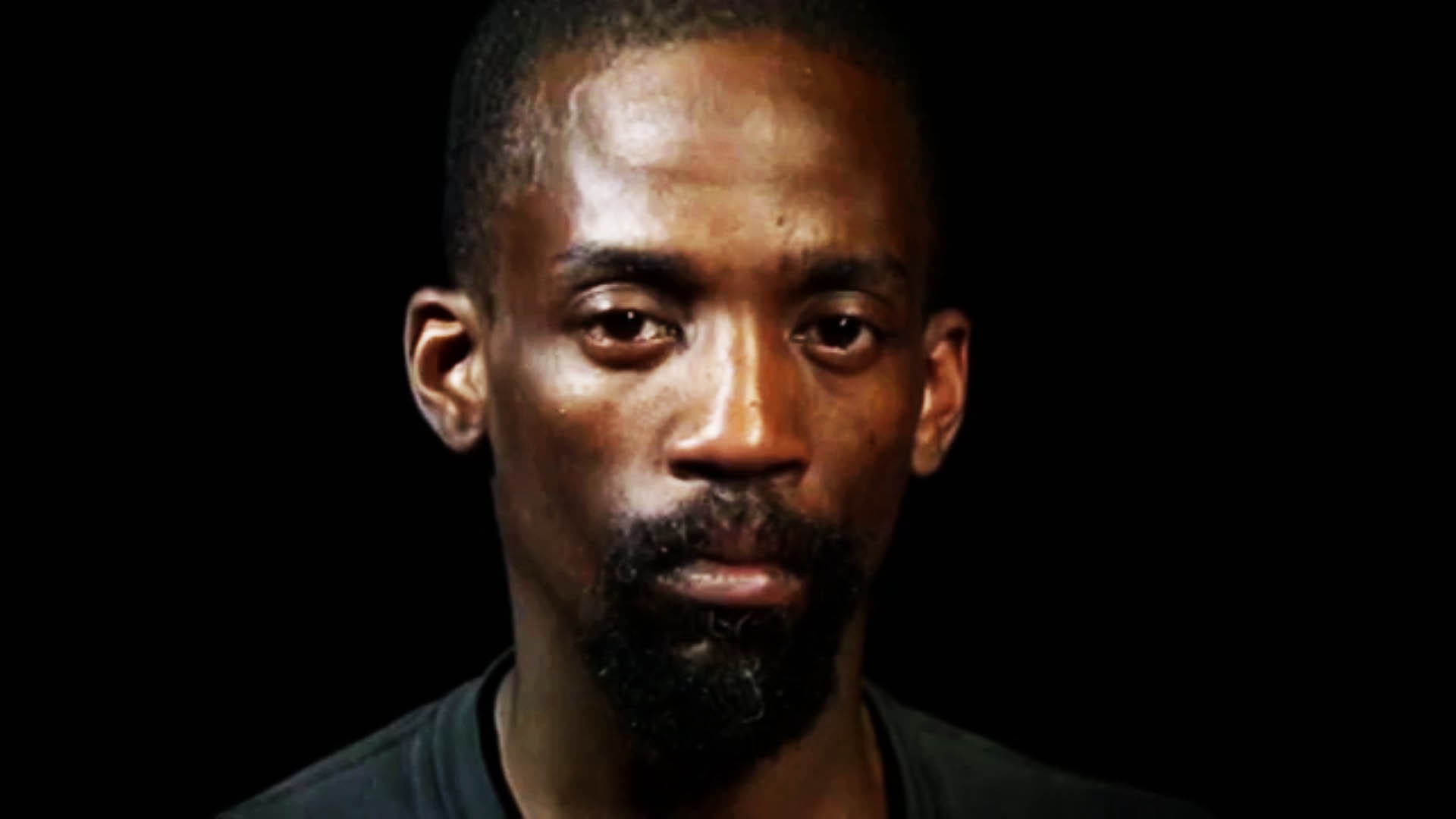

The Queer Nations/Black Nations conference of 1995 continues to shape the kind of debates we often pretend we are having for the first time. Artists and activists including Samuel Delany, Barbara Smith, Angela Davis and Isaac Julien gathered on a chilly New York morning in March to strategize and organize around issues concerning queer and diasporic blackness. Cultural workers were already beginning to ask what it would mean to be beautiful online but ugly and disproportionately criminalized offline. Foremost amongst them was the poet Essex Hemphill, who examined notions of visibility vs. non-visibility.

1995 belonged to an era of a largely text-based web culture. Less than one percent of the world’s population had internet access. Today, more than 40 percent do. That’s three billion people, connected across national and imaginary borders. 1995 was also the year Microsoft launched Internet Explorer 1.0. Netscape introduced JavaScript, a programming language used to manipulate and animate images, within the same year. Attendees of the Queer Nations/Black Nations envisioned this interconnected age but even they could not have imagined just how comprehensively the black image would be circulated and repurposed. After all, the internet was thought to be marked by the body’s absence. The modern proliferation of hashtags and body positivity movements continue to explode this origin story.

Even back then, Essex Hemphill was beginning to ask the right questions. How would the beauty of racialized and terrorized communities ultimately translate into online space? Where so many were excited by new forms of corporeality, he was already considering and poeticizing what being seen in pixels actually meant. His poem “Object Lessons” from 1992’s Ceremonies collection speaks to desiring the restorative potential of (self) objectification.

‘‘The pedestal was here,

so I climbed up.

I located myself.

I appropriated this context.

It was my fantasy,

my desire to do so

and I lie here

on my stomach.

Why are you looking?

What do you wanna

do about it?’’

The “context” is hostile to the dreams and fantasies of so many of its inhabitants. Hemphill’s “I” is both a vortex of nothingness and the focal point of possibility. His pleasure carves its own space, its own pedestal, and there’s nothing anyone can do about it. Such is the spirit that drives the contraband sharing and reproduction of a black image which celebrates itself in others. Hemphill insisted upon the body as a somatic interruption of unwelcoming territories; today, digitality provides the resources for these interruptions. Within today’s online communities, Presence is not a rehashed demand for recognition but a quest for interior pleasures, reflected and circulated outwards within already fragmented and globally scattered communities. It simultaneously stresses locality and the universal. Anyone with an internet connection can claim their position on this pedestal.

There are bodies, or beauties, that the world does not make space for. We know and live this. To counter that, these bodies have created their own alternatives online. From the precision of winged eyeliner on plus-size black bloggers and dark skinned women who vlog their skin-care regimens and lives, to the black queer men chronicling acid peel treatments via YouTube, each beautifying process is an assertion of resourcefulness, creativity and an ultimate faith in aesthetics as a healing practice. I don’t want to burden these daily routines with a symbolism that casts everything black women and femmes do as inherently radical. Sometimes looking good is just that. Looking good. Other times, it’s archival.

Within today’s online communities, Presence is not a rehashed demand for recognition but a quest for interior pleasures

Still, increased access to digital space and kinship encounters the same contentions that Hemphill anticipated. What would a beauty politics that isn’t grounded in our own negation even look like? Would we even recognize it? If beauty politics are indeed the politics of appearance and non-appearance, then the subversive image is equally prone to a commodification that advertises itself as a destabilization of the “norm.” We habitually gravitate to the image that sells us a diluted nonconformity; less femme, acceptably thick or curvy, a little further from all that is black and indigenous. Celebrations — mediated through online channels — of all that has been deemed “unconventionally” beautiful can feel a little bit like fads or just another way resistance is repackaged back to us.

Contrary to popularized mythology, women and femmes are not stupid. We recognize the inadequacy of beauty. We know about its intimate cohabitation with capitalism and how it sells our very refusal back to us. We are not the first to desire what destroys us. Maybe we don’t even want to be beautiful as much as we want what beautiful people have. Where my mother and her sisters would use the chalky residue from the walls of their Mogadishu home to powder their noses, I dab a smudge of NARS Sheer Glow Foundation (£31.00 without pump) on my own. I think of how many mouths back home my habits could feed. How I could have sent back so much more last time, in the form of remittances or even phone calls. The subterfuge which sustains my daily routines is not lost on me.

Spending the night with a Korean face sheet, or buying a lip shade I unconsciously know I already have is my own way of controlling the minutiae. We become a little different (not better) than we were yesterday, perhaps the only kind of change we can control. I navigate the world of black hair shops and hijab stalls (both places where non-black business owners watch my every move) and marvel at all the ways a color can make me a different person.

Playing with beauty like this can mean less surveillance. Being less of a deviation. As in I already have enough on my plate, so let me make what I’m serving palatable. Let me serve some realness. Some of us cannot indulge in the naval-gazing fantasies of dyed armpit hair, bad dress sense as ironic gesture and period blood art. We need what little social leverage our beauty can offer. Transgression is too often a domestic luxury. It is never read the same across all bodies. Strategically deployed ugliness rings hollow for those who have no choice but to live it. An ugliness that lends us just enough character is just beauty by another name. So much of a performed ugliness is a masochist desire for the antagonistic presence ugliness represents. No one really wants the ugliness that denies you a job, denies you fulfilling relationships with people who will love you without eventually humiliating you. The ugliness that means people will barge into you in the street without apologizing. The ugliness that was once enshrined in U.S. “Ugly” laws that prevented the disabled and unsightly from entering public space in major cities until the 1970s.

For such people, to live outside beauty is to live outside the threshold of ethics. Broadsheet newspapers speak of their metaphysical ugliness as regularly as high fashion magazines. The state holds hands with pop culture to brand them as eyesores and national concerns. Those of us who do not recognize ourselves look for online reflections of what we’ve always known to be true. Digital spaces can allow for a black image reimagined as soft, vulnerable and liberatingly opaque. Intensely personalized and curated versions of ourselves can be disseminated with our own permission amongst communities that seek to reaffirm first, slide in the DMs later. We devise and circulate our own nomenclature. Our own ways of being seen. Imagine Hemphill the poet wishing to see his out-of-print works available on the internet while running from the podium at poetry readings in order to vomit. This was his reality: IRL as too much to bear. IRL as something we, and our bodies, need to habitually escape. URL as refuge. URL as sanctuary.

Social platforms can document glamour-work. The currency of Instagram baddies and Muslimah beauty gurus (or the Muslimah baddie hybrid) lies in their ability to create a semblance of alternatives. They represent a widening of the imaginary. Not a complete reinvention of suffocating ideals but a widening nonetheless. Instagram accounts curating these trends like HijabFashion boast 2.8 million followers, many of whom are non-Muslims. Designers such as Dian Pelangi broadcast their globetrotting millennial beauty habits to an audience of 4 million. Ibtihaj Muhammad, an Olympic fencer and medallist, taps into the lucrative market with her clothing brand Louella. Alternative beauties can even be catapulted into the wider (read: whiter) mainstream, as shown by 2017’s Yeezy Season 5 show. Halima Aden, a 19-year-old Somali-American model, described as an “otherworldly beauty,” walked Kanye West’s show before being signed with IMG models. Her rise from specific Instagram Discover pages and Muslim fashion blogs to Paris and New York tells us what is possible or, inversely, what we can make possible. Gone are the days when the racialized relied only on rare and usually sensationalized misrepresentations in fashion magazines. Now, anyone can curate a dashboard to reproduce a beauty that both looks and feels familiar.

Sometimes looking good is just that. Looking good. Other times, it’s archival

“Mainstream”/“Eurocentric” beauty standards are empty coat-hanger labels that mean little nowadays (did they ever?) in the age of black and proxy-black Instagram models and plastic surgery courtesy of Dominican celebrity doctors who sculpt the kind of bodies that will never make it on to runways and silver screens. That doesn’t make them any less aware of their own beauty. The Muslimah MUAs with gracefully tailored modest wear craft their own communities. We create our own digitalized beauty sub-cultures. That doesn’t make them any less oppressive. But sometimes, you need them to exist. Sometimes you want your own version of The Beautiful Ones. Or even better, a beauty politics that isn’t at the expense of ourselves or others.

Outside, recognition can translate into street violence and aggression. To log on and take comfort in the digital spaces embodied by moments like World Hijab Day can be a form of communal restoration. Conceived by Nazma Khan in 2013, this annual sharing of imagery celebrates the mundane everyday styling of hijabs, shaylas and turbans. These displays of alternative fashion are a testament to weaponized beauty. When Muslimah fashion influencers are profiled by mainstream media outlets, the comments section is as snarky and vitriolic as expected. I don’t get why they wear these rags and still wear make-up. Hypocrites. Such are the musings of those who do not understand all the ways in which beauty is a shield needed most by those excluded from it.

#BlackOutDay, launched in 2015, is a digital event held on the sixth day of every month. Tumblr user and creator T’von Green (expect-the-greatest) wanted to circulate the black image in all its particularities: Damn, I’m not seeing enough Black people on my dash. Of course I see a constant amount of Black celebrities but what about the regular people? Where is their shine? With the help of fellow users Marissa Sebastian and Matthew-King Yarde, he promoted the hashtag and founded a site, which gave way to wider celebrations of black diasporic, disabled and gender non-conforming beauty. Responses were overwhelming as global netizens flaunted their selfies and candids, sharing those of others. The black image luxuriating in its own reflection.

#WhiteOut was the inevitable response. Other users were threatened by an unassuming and beautifully ordinary black image that was intended for mutual and consensual distribution. Nothing upends the commodification of blackness more than an interiority that hijacks the very machinery that seeks to control it. In doing so, #BlackOutDay climbed to the top of trending topics and search engine results. I spent much of March 6, 2017 scrolling through various feeds, marveling at the diaspora flaunting itself back at itself. #BlackOutDay was, and is, FUBU to the core.

Comments trolling hashtags that document alternative beauties function as a reminder of who determines beauty ideals offline. We are navigating the bastard child of ARPANET, the 1969 packet switching network and precursor to the modern internet that was funded by the United States Department of Defense. That it is to say, we expect such hostility to our beauty. Here, we weaponize what has been designed against us, one repressively long acrylic nail at a time.

Tiona Nekkia McClodden – Affixing Ceremony: Four Movements for Essex, Cyberspace, 2015.

Our electronic fantasies of shedding the dead weight that holds us back in our daily lives can seem insignificant when faced with reality’s totalizing violence. Picture the International Rescue Committee’s photographic records of the items Middle Eastern and East African refugees carry on their journeys. Cosmetic and grooming tools were a fixture in both the belongings of both men and women. Hair gels and oils. Nail polish. Face whitening cream. All stashed alongside nappies and medicine. It makes perfect sense how those who have ceased to belong to a fixed home need to desperately belong to their own bodies. Look good or else. Look younger than your years or else. The checkpoint/detention center/refugee shelter turns into another one of life’s runways. At first glance, the world of hashtags and lifestyle bloggers could not be more removed. Yet, again we return to the (self) image. Survival at ground level is something that needs to be captured on lens and digitally reproduced as proof; Yes, I survived this day. Yes, I deserve to be allowed in.

Hemphill was never too optimistic about this utopian cyberspace that would welcome “all that confusion,” all that ugliness, his carrier bag of “violent gestures, fractured soul, short fuses” and “dreams of revenge.” All his darkskint black. All his queer. All his broke and bitter and dying. He feared a transient black image; the kind we post and share on platforms we don’t own that can disappear as easily as they are created. Hemphill’s own fragmented archive is sadly a testament to this reality. He would die of AIDs-related complications by the end of 1995, before being able to put his rarer works on the internet.

Tiona McClodden, a filmmaker and visual artist, spoke to Hemphill’s fears of non-appearance and disappearance in her 2015 multimedia project Affixing Ceremony: Four Movements for Essex. Her work affixes Hemphill’s image in cyberspace, crystallizing him within the ambers of the net, using digital archives, sound, music, typography to rethink how the black image can outlast and transcend its creation. Much like Hemphill tentatively did, McClodden believes in a cyberspace that can, on its best days, facilitate “epiphanies”; the spiritual work we that we may uncritically call “self-love” in some circles. But we have to stay suspicious of aesthetic algorithms which are only refractions of what makes daily life so unbearable for so many. This means interrogating overpriced hijab lines marketed to communities that can hardly afford them. This means questioning why our reflections must always be constructed in the image of the lightest skinned, the racially ambiguous, the acceptably unacceptable. In the euphoric rush to document instead of being documented by others, we have to question what this entails. Who gets the make-up the lines? Who gains both social and financial capital? Who demands the unchallenged right to brand themselves as an alternative beauty, regardless of how rigidly they embody dominant beauty standards? Who is made invisible in our quest for visibility?

I’m not deluded enough to pretend I am ugly. Or monstrous. I am normative in all the ways that help me sleep at night while others don’t. Beauty standards are too slippery for absolutes and yet ultimately entrenched in the rejection of blackness. I can write this knowing I am beautiful or not at all beautiful or spectacularly average depending on who’s looking. What really matters is that I clean up fairly well. Or at least well enough to grasp at an intra-racial flavor of black beauty. Just give me a good hour and a bathroom. Technicalities become less important the more we imagine beauty as a project of incorporation we build towards, working with that we have, which may be less or more than we want.

Virtuality is what mirror is to screen. For those who fear what might be reflected back, hashtags such as #BlackOutDay are necessary interventions. We do not (yet) live in a world that wants our bodies as they are. We don’t live in a post-body internet, either. In-between these two truths lies the possibility of collective affirmation.