One night last winter in the relaxed atmosphere of a dinner here, Governor Rockefeller accepted a phrase that had been leveled at him as criticism by Democratic politicians. He conceded that he had an “edifice complex.”

—William E. Farrell, “State Mall, Rising in Albany, Becomes a Campaign Issue,” New York Times, August 18, 1970.

Long before Donald Trump, Nelson A. Rockefeller was a brash New York scion who financed his own political campaigns. In 1959, he defeated incumbent William Averell Harriman for New York governor and would win the office three more times before ascending to the vice presidency under Gerald Ford in 1973. Rockefeller had grand designs for his legacy, so he spent all of his nearly 15 years as governor remaking New York’s capital, Albany, and building a new one he hoped would be worthy of his name.

By the time the governor was finished with the city (whose population has never exceeded 135,000) he had obliterated 98 acres of densely populated city streets, including those that once made up the Gut, a neighborhood of aging brownstones and modest shops that presaged much of what the postindustrial Rust Belt would come to look like. Most of the news coverage of the time describes the Gut the way Rockefeller preferred that it be seen: a seedy region largely made up of brothels, dive bars, and drug dens. And while some of those things did exist (as is true of any city), it was more accurate to call it a working-class neighborhood with Italian immigrants and their extended families. Pre-demolition photos of the Gut look like they might have been taken in Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

Rockefeller had several options for destroying the Gut. He could run a highway through it, he could build and subsequently underfund a public-housing superblock, or he could leverage Albany’s prestige as the capital city of a wealthy state to call for the construction of an enormous civic project. The plan he eventually settled on, the Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza project, would do all three, setting the stage for the sort of immense population shift that usually comes only in the wake of a natural disaster. But because this conflagration was bureaucratically scheduled, state and local authorities were able to negotiate how fast and under what terms the exodus would occur — a blueprint that would be adopted again and again by state planners hoping to eradicate neighborhoods for more lucrative development, most recently in pre-Olympics Rio de Janeiro.

As technologies get older, they are more difficult to get rid of. Tools and practices are two plants in the same pot whose root structures eventually intertwine

After surmounting a variety of legal hurdles, New York State worked quickly to clear the land for the plaza, bulldozing buildings at a rate of two to three a day. Eminent domain made quick work of most absentee landlords happy to be rid of a property with declining value; those that owned where they lived fought the state’s low-ball offers in the courts with mixed results. Within a year, most of the buildings had been removed. World War II veterans said it looked like a European city after a bombing campaign. In its place rose Empire State Plaza, an enormous complex of concrete, marble, and light.

The Empire State Plaza was the embodiment of Rockefeller’s technocratic vision for government — an efficient, centralized platform from which to project the awesome postwar power of America. It was supposed to encompass everything that enlightened government was meant to champion: efficient disbursement of public services mixed with enriching cultural and scientific achievements. It contained a natural history museum, the entire state’s DMV bureaucracy, offices for every state legislator and the governor, two underground concourses of shopping, several parking garages, a world-class performance hall, reflecting pools, a bomb shelter from which governing could take place, millions of dollars of modern art, a laboratory specializing in the development and manufacture of antitoxins, and offices for the Department of Law that would be housed in the auspiciously named Justice Building. Rockefeller promised that his project would mark “Albany’s transformation into one of the most brilliant, beautiful, efficient and electrifying capitals in the world.”

Transform Albany it did, but few have described the plaza as brilliant or beautiful. Progressive Architecture described the first model of the complex as “a naive hodgepodge of barely digested design ideas … Rumors of Le Corbusier, eavesdroppings of Oscar Niemeyer, threats of Albert Speer.” Art critic Robert Hughes agreed, wrote this in 1981 (after the plaza had been completed for about a decade): “It is designed for one purpose and achieves it perfectly: it expresses the centralization of power, and one may doubt if a single citizen has ever wandered on its bleak plaza … and felt the slightest connection with the bureaucratic and governmental processes going on in the towers above him.”

As a pedestrian in Albany, it is difficult to argue with Hughes. If you arrive by car to Albany, the entire Empire State Plaza is visible from I-90, just as the highway descends into the Hudson Valley, and a dedicated exit ramp takes your car uninterrupted into its expansive subterranean network of parking garages. One can enter and exit the plaza, visit any of the hundreds of offices and labs, and even take in a show or visit the museum without breathing city air. But if you walk to the plaza, you are shown impermeable slabs of rock and marble.

Throughout most of Albany you can see the tip of the plaza’s Corning Tower, the tallest building in New York outside New York City. As you walk to the plaza from the west, downhill along Madison Avenue, the tips of the four identical agency buildings come into view. They stand behind the governor’s larger, center tower like dutiful soldiers. On the corner of Swan and Madison the early 20th century brownstones give way to the state’s Department of Motor Vehicles central office. It is a single block-long slab of white marble with no visible entrances, flanked by several war memorials in a pocket park. The DMV was the first building finished and a portent of things to come. Robert D. Stone, the commissioner of the Office of General Services (the department in charge of overseeing the project) said of the building, “This kind of design simply lends itself to the type of conveyor system that the department wants.” Paper and people would begin at one end of the building and be spit out the other side.

Certain technologies, when first introduced, temporarily stand as explicit, “vulgar” announcements of long-established social relations

If you keep walking east, past the DMV, the road slopes down but the plaza remains flat, a plateau rising a story above you within a span of half a block. At street level, the sheer wall of rough granite eventually gives way to an array of glass doors that lead you down into a bright white-marble hallway. You are now inside Empire State Plaza’s series of underground passageways called the Concourse, part airport, part Roman coliseum. It’s like walking into a scene from an Alejandro Jodorowsky movie, only there’s no nudity, just security cameras, some anodyne modern art, and government employees as far as the eye can see.

During business hours, and especially when the legislature is in session, the Concourse is as busy as any suburban mall, but because everything is so far apart, it appears as though everyone is walking to nowhere in particular. The Concourse plays host to everything from rope-line protests as the governor walks from his offices to the nearby convention center to regional weekend farmers’ markets, but none of these activities seem in harmony with the underground facility. It is a space of transition, a vector from one place to another rather than a site of civic or even economic activity — a gilded sewer of administrative authority.

The north side of the plaza meets the street at grade. This is the side with the cuboid Justice Building and ovoid performance hall dubbed, appropriately enough, The Egg. These geometric buildings act as foils to the New York State Capitol Building across State Street. Built in 1880, the Capitol Building is an equally imposing piece of architecture, albeit in a different style from a different time. Like Empire State Plaza, it repels the rabble, but with a tall staircase and an immense lawn in what is an otherwise dense urban environment.

It is always windy in the plaza, yet the reflecting pools stay glass-still. Standing with the four agency buildings to your back and the Corning Tower in front of you, the rest of the city utterly disappears. Instead there is just sky, parking garages, and warehouses for a state’s worth of bureaucrats.

How our lived spaces are made — from architecture and city planning to the design of our social media and digital devices — is always deeply political. Technology, as philosopher Bruno Latour famously declared, is “society made durable.” Society is the constant conversation we have with one another about how to manage our collective affairs. Tools, by virtue of their purpose of making our lives easier, have social consequences: Easier by what metric? For whom? At whose expense? When a technology stabilizes in form and function — like, say, a bicycle, a bomb, or a cell phone — this is because of compromises among actors.

Most theorists studying the relationships between society and technology generally agree that as technologies get older, they are more difficult to get rid of. An invention gains momentum until even its inventors cannot control its trajectory or velocity. Once built, our inventions afford or encourage some actions which tend to reinforce its place in society, and discourage those actions that tend not to, as Anique Hommels has argued in Unbuilding Cities: Obduracy in Urban Sociotechnical Change. Tools and practices are two plants in the same pot whose root structures eventually intertwine. Technological systems are like glasses that you forgot you were wearing — that is, they come to make up our conception of what has always been, and the possibilities for debating and interpreting them begin to fade.

The governor’s office in Empire State Plaza is practically a panopticon, allowing state employees to surveil the entire city while making it nearly impossible to see in

Hommels has identified three sorts of explanations for technology’s “obduracy,” or its tendency to persist: (1) it becomes a dominant frame, (2) it embeds itself into everyday life, or (3) it establishes a persistent tradition that makes it logistically difficult to change. Switching which side of the road a country drives on is exceptionally difficult not only because of all the technical logistics but because of the history, values, and personal feelings bound up in driving. Making big changes to cities is even more difficult, because all three of these models of obduracy are happening at once in such a way that each compounds the force of the others. What were once alien visitors — New York City’s subways, the Eiffel Tower, Empire State Plaza — become indelible aspects of a city.

But before these sorts of upheavals become obdurate and durably woven into an urban fabric, they first appear as obvious, overt. Similarly, certain technologies, when first introduced, reveal otherwise hard-to-discern allegiances and interests and embedded ideologies that will eventually again become ignored or hard to discern. These technologies — the email that reminds you how you’re never not working; the selfie that shows identity has always been performance, the government complex that makes bureaucratic contempt for street-level life plain — temporarily stand as explicit, “vulgar” announcements not of new social relations or arrangements but of established ones that become hard to perceive as we live with them. What was once disparate and ephemeral is consolidated into a conscious experience, unveiling to us, sometimes in strange and distorted forms, the social relations that become invisible with time.

How long and how intensely a technology seems “vulgar” before it fades into the background is a useful barometer of a society’s willingness to embrace whatever ideology that technology has made it impossible to ignore.

Slow and steady changes can accomplish a lot with far less pushback, whereas dramatic changes invite equal but opposite reactions. This is never more true than when political changes take shape in physical artifacts. But no labor dispute, lawsuit, direct action, Senate confirmation hearing, or eviscerating architectural review could stop Empire State Plaza. Through sheer executive force, Rockefeller got what he wanted, with little of the compromising and embedding that would have gone on in more complicated scenarios. The ways in which a technology gains champions or becomes tightly interwoven with a practice or culture over time did not have to happen for the plaza to persevere. This makes Empire State Plaza a rare example of a petrified vulgar technology.

It can be difficult to keep in one’s head all the organizational charts and histories that make up the undemocratic aspects of American governance, but the tall, cold surfaces of Empire State Plaza convey government excess and unchecked power experientially. It is an unusually explicit and enduring expression of the underlying authoritarianism of much of the U.S.’s political elite. It is part and parcel of the approach to statecraft that came out of Rockefeller’s wealth and status and went into his heavy-handed polices. Rather than use the legislative process to pass laws that, say, prohibit loitering around a public building, Rockefeller just built a plaza that makes it physically difficult to loiter, or protest. The governor’s office in the plaza is practically a panopticon, allowing state employees to surveil the entire city while making it nearly impossible to see in. The offices are even soundproofed.

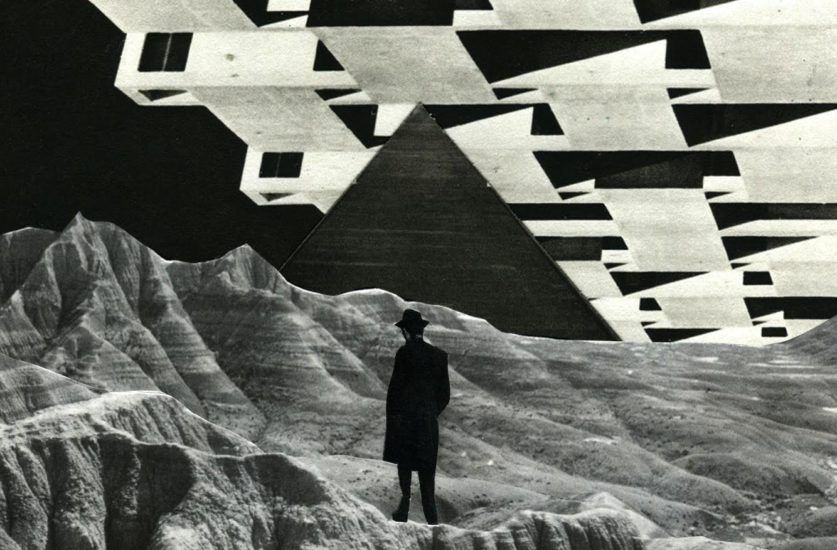

Unlike the plaza, many of the world-changing inventions of today are intangible. There are a thousand little Rockefellers looking to build their pyramids in our pockets

It is no coincidence that the same wealthy governor that built a plaza with “threats of Albert Speer” was also responsible for the ruthless crushing of an uprising in the overcrowded Attica prison. And while Rockefeller was criticized for both the plaza and Attica, buildings persist far longer and are far more visible than imprisoned bodies. One has to make an effort to learn about the events of Attica; one need only visit Albany to see Rockefeller’s political philosophy erected in marble.

According to a 1969 article from the New York Times, the governor enjoyed asking his pilot to divert his plane slightly off course so he could look at the plaza from the perspective at which it, like many other government-built architectural projects, was meant to be enjoyed: from high above. From the vantage points necessary to view the whole structure, to the vistas that it creates, Empire State Plaza takes all our spatial metaphors about governance, about the political distance that can open up between an elected government and the people it purportedly serve, and makes them literal.

The anger and frustration that the plaza has and still evokes has to do not necessarily with the particulars of the dubious politics by which it was built but with how that politics is embedded and transfigured within it: how all that marble and glass is arranged, the space it occupies, the sensual and aesthetic qualities of all that concrete. When you stand in the Concourse, you are acutely aware of what Paul Virilio would call the technical vitalism of modern governments. The subterranean passageways and the DMV building afford a speed and vitality to elected officials and bureaucrats, allowing them to move from one office to the next with no concern for any sort of climate.

Outside in the open-air plaza, there is no vitalism, only void and surface: the very antithesis of Jane Jacobs’s prescription for lively cities. Nothing is at a human scale. The doors are tall, the agency buildings “float” on their own pedestals, with no windows visible at eye level. One urban-design theory suggests that humans are most comfortable when we can see clear boundaries in our environment. The plaza offers only monumental buildings. Its uniformity and visual hierarchy conveys the sense that boundaries have been transcended by a singular, total task embodied and imposed by the plaza. If “a house is a machine to live in,” as Le Corbusier’s famous axiom goes, then Empire State Plaza is a machine to rule in.

Even if you don’t know anything about architecture, you can viscerally sense its power. It can lay bare the political and social relationships that are otherwise hidden in obfuscating legalese or misdirecting rhetoric. Rockefeller’s construction projects didn’t hide the political endorsements they were designed to secure, and the final products continue to testify to who had access to government and who did not, establishing norms about who the state’s clients are. Empire State Plaza accommodates the suburban middle class and moneyed elites for whom physical access to the literal halls of power is made easier; meanwhile, those left in cities like Albany find those halls of power are looming over them, but always out of reach.

Empire State Plaza was not the first and certainly would not be the last instance of Rockefeller consolidating and projecting immense power, but there were few times where both experts and average citizens alike could readily see and understand how much power he was amassing. Empire State Plaza was what earned him the most direct, frequent, and high-profile references to Nazis — not his role in the Attica uprising or his draconian drug laws.

This points to a recurring danger with “vulgar” technologies: that we will direct our anger and frustration at them rather than the pre-existing conditions that they merely expose. The frequent handwringing over social media and devices works similarly: Their novelty consolidates and makes unmistakable the social alienation and disconnection that was already prevalent. Authors like Sherry Turkle and Nicholas Carr, for example, put the onus on the technologies themselves, which is akin to holding Empire State Plaza accountable for its own construction, and admonishing anyone that worked there for perpetuating undemocratic authority. New York State employees and iPhone users are certainly complicit and inextricably linked to oppressive systems, but the technologies they are bound to are highlighting social ills, perhaps perpetuating them, but not creating them.

We can take heart that there will be fewer Empire State Plazas in the near future. Urban planners have made a course correction away from top-down decision making in the style of Robert Moses and Nelson Rockefeller toward more emergent and participatory systems that values the sort of dense urbanism that was once found in the Gut. At the same time, we would do well to be on the lookout for new pernicious forms of urban control that rely less on authoritarianism and more on the algorithmic deduction of optimally photogenic and quirky neighborhoods.

Still, when vulgar technologies reveal ideologies, we must seize the opportunity this presents. Unlike Empire State Plaza, many of the world-changing inventions of today are intangible. There are a thousand little Rockefellers looking to build their pyramids in our pockets. The value of a vulgar-technology perspective is to show that while material and social conditions mutually reinforce one another, social and political structures must ultimately be analyzed and changed. Technological determinism is a distracting myth.