On November 11, Sylvester Stallone will release Rocky IV: Rocky Vs. Drago, a director’s cut of his 1985 hit Rocky IV. Although it’s not immediately clear that anyone asked for this reboot, upon watching the 90-minute documentary about the making of this director’s cut, it is clear that Stallone is excited to give it to us. Developed during pandemic downtime, Stallone says the point of the director’s cut is to go back in time and get the film right, turning what he admits was “mostly montage” into an actual drama. But a drama about what?

Widely popular at its release yet lambasted by critics, the original Rocky IV is often seen as an era-standard piece of Cold War propaganda. In one of the more literal allegories ever devised, it pits the robotic yet perpetually glistening Soviet boxer Ivan Drago against rough-and-tumble, rags-to-riches Rocky Balboa, a product of the American melting pot and work ethic — a match between cold, mechanical socialism and passionate, human capitalism.

Stallone sees Rocky IV as a film about humanity and individualism, with a series of technological obstacles from both the East and West that Rocky must overcome. His final task, defeating Drago (and socialism), is the ultimate proof that Drago is not a machine but merely a man. However, Rocky IV is more productively read as a film about technology’s role in creating a sense of capitalist humanity. To make capitalism seem human, the West’s dependence on technology had to be hidden, while Soviet technological capacities had to be embellished in alignment with the USSR’s own propaganda about itself: that a command economy could produce merciless and unmatched excellence typified by the achievements of its automaton-like athletes. Although the Soviet Union is no more, similar claims were made against China in the most recent summer Olympics, suggesting that concerns around the technologization of sport remain centered on its assumed detraction from the humanity of athletes.

Before the 1930s, Soviet sport was conceived as a liberatory and revolutionary form of physical activity for everyone, and no state funds were concentrated on the professionalization of a few star athletes, as in capitalist countries. Athletes were amateurs and most sporting competitions were held nationally between factory clubs or between other worker sports clubs around Europe. The Soviet Union did not even participate in the Olympics.

As Drago warns the world after committing manslaughter in the ring, “I defeat all man.” Rocky is not simply a representative of America but of humanity, up against a hybrid, post-human superbeing

This changed with the advent of the Cold War. Sports quickly became a popular avenue for proto-military training and state public relations, precipitating its professionalization. While keeping the formal title of amateur, successful Soviet athletes were allowed to skip work to train and would receive cash bonuses for winning prestigious competitions. Some athletes even claimed to receive a daily ration of nutrient-dense black caviar a day. By the 1980s, athletes were explicitly professionalized, with separate salaries and housing arrangements.

To some extent, professionalization also meant technologization. The “scientifically” planned and organized approach to the economy was adopted for sports development as well, with the Soviet Union investing in resources and researchers to develop a sports science. While these efforts produced foundational sports science theories, they primarily came through an organized account of an athlete’s training regimen, easily tabulated with pen and paper rather than the futuristic technologies on display in the film. What made the USSR successful in international sport was the state’s capacity to generalize sports science (and steroids) into athletic development programs across the country. In other words, the technology involved was mainly centralization and the state’s de facto monopoly on athletics.

But in the West, Soviet athletic success was often seen as a product of general technoscientific supremacy rather than a question of state priorities and social organization. This framing mirrored many other Cold War paranoias, such as the U.S. falling behind in funding for STEM subjects, the space race, and public and private R&D spending. It also disguised the degree to which the profit-oriented monopolies of capitalism were failing to achieve greatness and were palpably stagnating.

The Soviets’ entrance into the Olympics in 1952 turned the international athletic competition into a proxy war between the East and West, codified for example in Disney’s movie, Miracle, which helped mythologize the 1980 U.S. men’s hockey team. Pulling together a group of collegiate amateurs, coach Herb Brooks builds a true team to defeat the Soviets, who were amateurs only in name. The Soviets are displayed as a well-oiled, emotionless machine, whereas the Americans beat them by bonding together as individuals with complementary talents. For Olympic boxing however, the Cold War rivalries were held at bay by the U.S.-led boycott of the 1980 summer Olympics in Moscow and the subsequent Soviet-bloc boycott of the 1984 games in Los Angeles. By the time Rocky IV was released, it had been nearly a decade since the U.S. and the Soviet Union had faced off in the ring on the Olympic stage.

This relationship between athletics, economics, and technology forms the backdrop for Rocky IV. In the film, Drago, an “amateur” boxer by Olympic standards but more like a technologically manufactured athletic specimen, is on a tour of the U.S. to fight in exhibition matches that the film frames as dubious gestures of cultural exchange and political détente. What they really are meant for is to show off the Soviet Union’s superior technological prowess and, by extension, the inevitability of totalitarian victory. Drago embodies the typical Cold War anxiety around the USSR surpassing the United States in industry and technological development, but in the particular form of a cyborg-like man-machine.

Training for Drago entails a regime of bureaucratic and scientific management; for Rocky it is a pointed exercise in isolation and deliberate deprivation

Apollo Creed, Rocky’s former antagonist turned best friend, comes out of retirement to fight Drago in the hopes of reviving his own career, but this does not go well: Drago kills him in the ring with a punch to the head, leading to his famous line, “If he dies, he dies.” This sets up a retribution match between Drago and Rocky to take place in Russia on Christmas Day. In this fight, Rocky is not merely an underdog but a potential casualty. As Drago warns the world after committing manslaughter in the ring, “I defeat all man.” Can Rocky survive the match, let alone win, against the Russian killing machine? He is not simply a representative of America but of humanity itself, going up against a hybrid, post-human superbeing. In the press conference announcing the fight, Drago’s trainer, Nicoli Koloff, is confident he will defeat Rocky stating that, “It’s a matter of size. Evolution. Isn’t it gentlemen? He is the most perfectly trained athlete ever … Drago is a look at the future!”

In the runup to this climactic fight, we are treated to a sequence that is the cornerstone of every Rocky film: the training montage. These often quite extended scenes reflect the American dream ideology of hard work, a Weberian capitalist work ethic, and the process of ascetic self-transformation that many boxers undergo before a bout. Across all the Rocky films, the montages of his training consistently critique consumerism and luxury: They engender a softness that sets one up for failure. Sometimes it’s Rocky’s opponents who are insufficiently Spartan; sometimes, as in the third and fourth installments, it’s Rocky himself. In Rocky IV especially, he is depicted as having more wealth and fame than he knows what to do with and the films unfold his recurrent journey to “find himself” amid his life of luxury.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MXMSsvozMc4

To fight Drago, Rocky chooses to train in Siberia, specifically requesting a remote cabin and barn for this purpose. While Drago trains in a steamy room full of coaches and scientists, using metal training contraptions that glow with the red tint of a digital communist imaginary, Rocky works out in the snow-laden tundra or in the barn, using such elemental implements as logs, stones, and sleds. Although at first it may seem like the message is that Rocky doesn’t need equipment or technology to beat Drago, the real difference lies in the forms in which ultimately similar means of production are embedded: Training for Drago entails a regime of bureaucratic and scientific management; for Rocky it is a pointed exercise in isolation and deliberate deprivation. This contrast of modes is established by alternating shots in the montage in which Rocky and Drago appear to mimic each other’s training exercises. When Rocky drags a sled through the snow loaded up with rocks and his half-drunk in-law Paulie, Drago pushes against a sled machine that records his speed. When Rocky loads heavy stones into a cart, Drago performs a barbell power clean with electrical nodes extending from his chest and shoulders. The only asymmetry in the montage is Drago’s use of performance-enhancing drugs, themselves a form of pharmacological technology, dramatically injected into his shoulder mid-workout.

Rocky’s best shot at victory, we are led to believe, comes from a kind of inversion of history, in which the rich, professional boxer must escape the urban decadence of modern life and feed off the solitude of the USSR’s far hinterlands, while the so-called amateur Soviet boxer trains with a preposterous number of gadgets and machines, most of which were entirely fictional. Although actual Soviet boxing films from the era confirm the use of some of the equipment seen in Rocky IV, such as a force plate to measure punches, in reality, there was relatively little mechanization of the broader training process. In fact, a promotional video of Kazakhstani boxers even shows them lifting and throwing boulders just like Rocky. But in Stallone’s film, technology is recruited to stand in as a corrupting influence. As Drago’s relation to technology is overemphasized to the point where he is basically a piece of technology himself, Rocky’s must be disavowed: He is not training to become a machine but to fend the machines off and to reassert the force of human will. He must shake off the wealth and technology that has encrusted his life outside the ring and become his true self again.

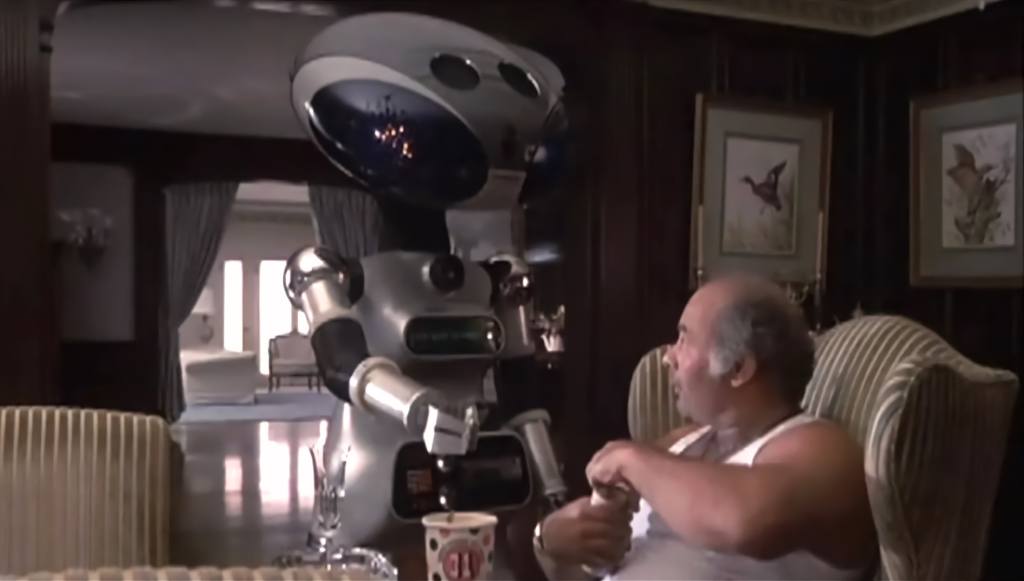

But it is the most conspicuous piece of technology in the film that underscores Rocky’s hidden reliance on technology: that, of course, is Paulie’s robot.

Critics have generally read the robot as a gimmick without any meaningful connection to the plot, and Stallone has promised that the robot will be removed in the new director’s cut. But its removal would be a shame, as it throws the film’s portrayal of robotics out of balance: Paulie’s robot (a humanoid robot) is an obvious foil for Drago (a robotic human), and their dialectical pairing articulates the film’s double-sided critique of technology: It can make you too soft, or it could make you altogether insensate; either you are weakly dependent on it or utterly taken over by it.

Paulie becomes a cyborg different from Drago: dependent not on steroids and sport science to become impervious to human contact but on robotic attention to supplement his inability to connect

Presented to Paulie as a birthday present early in the film, the robot seamlessly navigates Rocky’s home, cake in hand, all while playing music and wishing “Happy Birthday” in the conventional tin-can robot voice. A few scenes later, the robot returns to serve Paulie a beer while Rocky, Paulie, Apollo, and Adrian discuss whether Apollo should fight Drago. The robot compliments Paulie as it serves him, by which we learn that he has re-programmed it with a feminine voice. He refers to the robot as “his girl” and even declares, “She loves me,” during a discomfiting close-up. (Adrian and Apollo seem so disturbed by this they almost break character.)

Like much of Drago’s training equipment, autonomous service robots did not and do not exist. The robot used in the film is an actual robot, though, and not a person in a costume. It was a SICO model made by International Robotics Inc., a company specializing in human-controlled robots since the 1970s. These robots are primarily used for marketing purposes (trademarked as Techno Marketing), where robots go to trade shows, corporate events, and sales conferences to further encourage the circulation of commodities. When news of the robot’s removal from the director’s cut leaked, International Robotics Inc. CEO Robert Doornick wrote an impassioned letter about his disappointment with Stallone’s decision, claiming that the SICO robot is not a prop but a “socio-psychological phenomena” that facilitates human connection through the company’s charity work in school and hospital visits. Doornick also claimed that Stallone was hoping to avoid having to pay royalties to SICO, who, despite being the first non-human union member, collects them like any other SAG-AFTRA actor.

Through Paulie’s robot we see that — unlike the Soviet Union, whose technology is rooted in the sphere of production — technology for Team USA hides in the sphere of social reproduction, with the robot performing care work. It is Paulie, a weak, duplicitous man without a family of his own, who needs the charitable services of the SICO robot, reinforcing the ambivalent view of technology. Paulie becomes a cyborg in a different way from Drago: dependent not on steroids and sport science to become impervious to human contact but on robotic attention to supplement his inability to connect.

Through Paulie’s robot we see that — unlike the Soviet Union, whose technology is rooted in the sphere of production — technology for Team USA hides in the sphere of social reproduction

Rocky supposedly cleanses himself of his reliance on technology in the training montage, but at the end of film, during the great bout, the robot makes one last appearance, dressed as Santa Claus to babysit Rocky and Adrian’s son while they are in Russia. The automated childcare provided by the robot lets the Balboa family have it all, with Adrian supporting Rocky in the ring and their son safely watching the fight at home on TV. This scene reflects the real impact of the robot in the lift of Stallone who hired it to entertain and support his autistic son.

Rocky is willing to lean on his wife, already a threat to the theme of individualist transformation, but the film unwittingly admits that this is only possible because of SICO’s care work — the “reproductive labor” it performs, to borrow a term from Marxist feminists such as Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James and Leopoldina Fortunati. Rocky uses his wealth to automate care work at home so he can find his primal, human core in his journey through Russia, owing his victory to the SICO robot and Adrian as much as to himself.

In the climactic struggle, Rocky, as the embodied spirit of good capitalism, wins because he is aware of his humanity, unlike Drago who has been fashioned into a soulless socialist machine. In his post-fight speech to the audience, Rocky attempts to summon a new form of unity by calling on everyone in the U.S. and Soviet Union to come together under the banner of abstract humanity — a victory speech uniquely appropriate for a clearly concussed boxer. Of course, this is really a call for a more humane capitalism, one that believes it can exist without the cold industrialism of Soviet socialism and the luxurious excess of American capitalism that makes men like Rocky into Paulies. The SICO robot’s presence breaks this fantasy, demonstrating how Rocky as well as Drago are enmeshed in sociotechnical relations that they cannot escape simply by exchanging blows to the head.