SYLLABUS FOR THE INTERNET is a series about single books or bodies of work written prior to the rise of the consumer internet that now provide a way to understand the web as we know it today. View the others here.

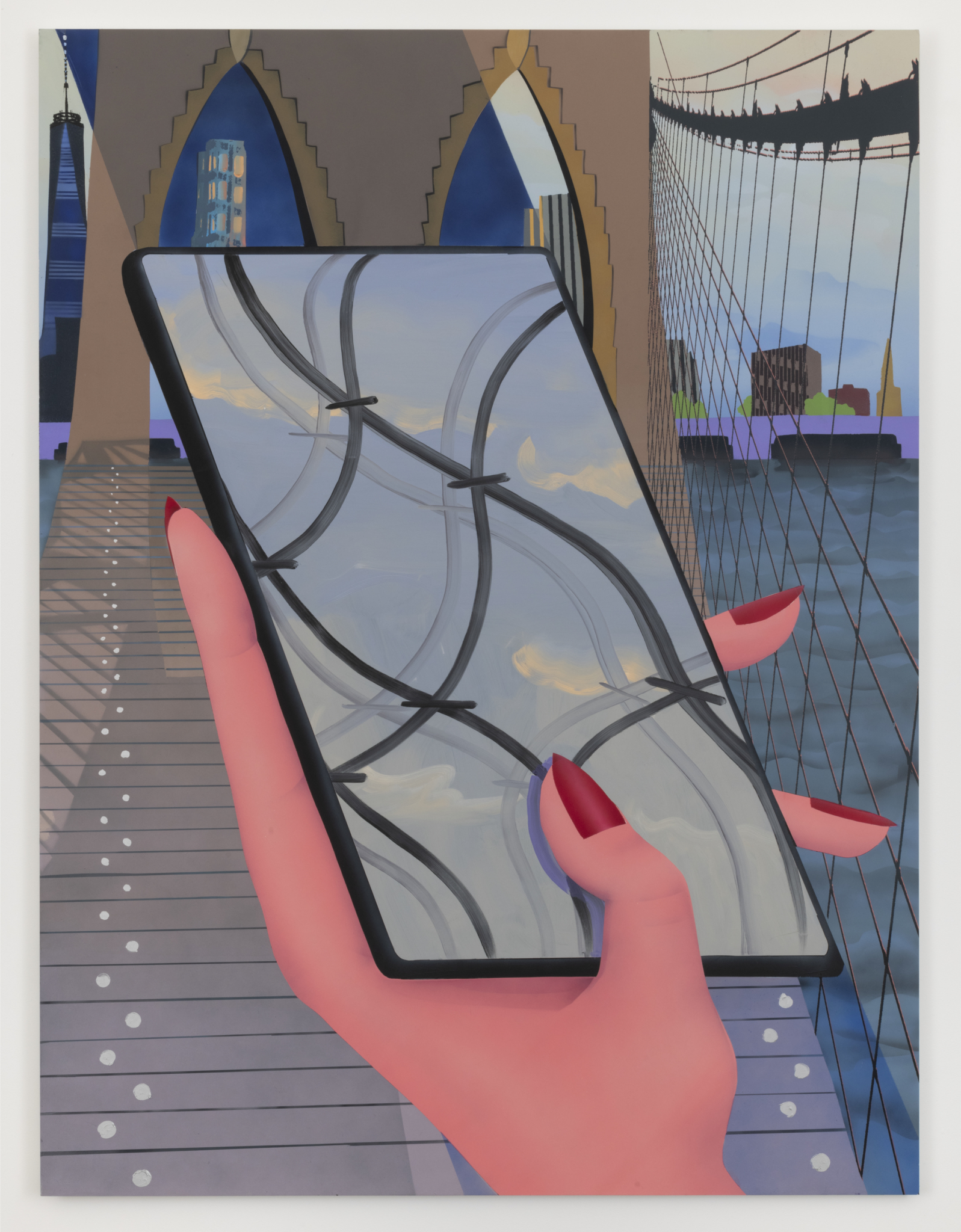

Whenever there are disturbing revelations about the actions of a tech company, or around a certain set of technologies, a cycle begins that is becoming depressingly familiar. The initial story draws attention to the issue; in response to the initial exposé, there is a further outpouring of commentary; those in positions of authority are exhorted to do something; nothing much actually changes; and then a few weeks later, the cycle repeats. From Facebook to Amazon, from e-waste to the energy demands of crypto-currency, from facial recognition to the latest wearable gadget — we consumers find ourselves buffeted back and forth between the promise that high-tech devices are going to solve all of our problems, and the mounting evidence that those same devices are exacerbating many of our problems. And through it all, even as frustration mounts, we still find ourselves posting on social media, dutifully replacing our smartphones, taking advantage of next-day shipping, and streaming the latest show that everyone is talking about.

Surveying the state of the high-tech life, it is tempting to ponder how it got so bad, while simultaneously forgetting what it was that initially convinced one to hastily click “I agree” on the terms of service. Before certain social media platforms became foul-smelling swamps of conspiratorial misinformation, many of us joined them for what seemed like good reasons; before sighing at the speed with which their batteries die, smartphone owners were once awed by these devices: before grumbling that there was nothing worth watching, viewers were astounded by how much streaming content was available at one’s fingertips. Overwhelmed by the way today’s tech seems to be burying us in the bad, it’s easy to forget the extent to which tech won us over by offering us a share in the good — or to be more precise, in “the goods.”

It is often easier to describe an intimidating dictatorial system than it is to explain why people go along with it. Thus, the bribe

Nearly 50 years ago, long before smartphones and social media, the social critic Lewis Mumford put a name to the way that complex technological systems offer a share in their benefits in exchange for compliance. He called it a “bribe.” With this label, Mumford sought to acknowledge the genuine plentitude that technological systems make available to many people, while emphasizing that this is not an offer of a gift but of a deal. Surrender to the power of complex technological systems — allow them to oversee, track, quantify, guide, manipulate, grade, nudge, and surveil you — and the system will offer you back an appealing share in its spoils. What is good for the growth of the technological system is presented as also being good for the individual, and as proof of this, here is something new and shiny. Sure, that shiny new thing is keeping tabs on you (and feeding all of that information back to the larger technological system), but it also lets you do things you genuinely could not do before. For a bribe to be accepted it needs to promise something truly enticing, and Mumford, in his essay “Authoritarian and Democratic Technics,” acknowledged that “the bargain we are being asked to ratify takes the form of a magnificent bribe.” The danger, however, was that “once one opts for the system no further choice remains.”

For Mumford, the bribe was not primarily about getting people into the habit of buying new gadgets and machines. Rather it was about incorporating people into a world that complex technological systems were remaking in their own image. Anticipating resistance, the bribe meets people not with the boot heel, but with the gift subscription.

The bribe is a discomforting concept. It asks us to consider the ways the things we purchase wind up buying us off, it asks us to see how taking that first bribe makes it easier to take the next one, and, even as it pushes us to reflect on our own complicity, it reminds us of the ways technological systems eliminate their alternatives. Writing about the bribe decades ago, Mumford was trying to sound the alarm, as he put it: “This is not a prediction of what will happen, but a warning against what may happen.” As with all of his glum predictions, it was one that Mumford hoped to be proven wrong about. Yet as one scrolls between reviews of the latest smartphone, revelations about the latest misdeeds of some massive tech company, and commentary about the way we have become so reliant on these systems that we cannot seriously speak about simply turning them off — it seems clear that what Mumford warned “may happen” has indeed happened.

The bribe can be a useful tool for understanding how we got where we are, and can be useful to keep in mind as we think about where we want to go next.

It is challenging to affix a single category to Lewis Mumford. He has been called a literary critic, a sociologist, a philosopher, a historian, and a “prophet of doom,” though he preferred to see himself as “an exponent of the Renewal of Life” — one who delivered grim warnings in the hopes that those ominous words would lead people to change their course. It seems best to see him as a social critic and public intellectual. Mumford was born in the final decade of the 19th century, and died at the start of the 20th century’s final decade. A child of Flushing, Queens, the experience of coming of age in that growing metropolis kindled in him a lifelong fascination with the ways people built cities, and those cities in turn built people.

As a young man, Mumford was associated with New York’s literary scene — contributing to publications including the Dial, Freeman, the New Republic, Commonweal, New Masses, and eventually writing columns on architecture and art galleries for the New Yorker. His early works were in keeping with the literary circles he was engaged with at the time, though from his first book, 1922’s The Story of Utopias, in which he explored the features of imagined ideal societies, he established a core theme that would play like a leitmotif throughout all of his work: “the fundamental difference between the good life and the ‘goods life’” — the way that consumption came to be seen as the highest moral and social value.

Mumford would write four more books, three pamphlets, and dozens of articles over the next decade. But while he explored technological themes in these early works, it was not until 1934’s Technics and Civilization — the first installment of his four-volume Renewal of Life series, a sweeping attempt to explain how the world had reached its present state and hypothesize what was to come — that Mumford devoted an entire volume to the matter of technology. Considering the reputation he would develop later in his life, it is worth noting that Technics and Civilization is a very hopeful book. Written in the interwar period, it is representative of the belief that, having witnessed the destructive power of technology in The Great War, societies would now work to turn the machine into a tool of life rather than an instrument of death. Even as he acknowledged the “manifest blessings of the machine,” Mumford was aware of the ease with which a blessing becomes a curse, and thus warned of the need to assimilate the machine to human values and needs, lest the machine’s values and needs be prioritized. As he put it, “the belief that the social dilemmas created by the machine can be solved merely by inventing more machines is today a sign of half-baked thinking which verges close to quackery.”

By 1951, the year he completed the Renewal of Life quartet, the guarded optimism with which Mumford had written Technics and Civilization had largely turned to ash. In the intervening years, he had published an impassioned attempt to sound the alarm on the dangers of fascism (1939’s Men Must Act), a discussion of what was necessary to safeguard democracy from the fascist threats within and without (1940’s Faith for Living), an attempt to plot a safe course for humanity in the aftermath of the atomic bombs (1946’s Program for Survival), and a woebegone biography of his son, Geddes, who had been killed on the Italian front during the war (1946’s Green Memories). To the extent that an increasingly tragic tonality started to become characteristic of Mumford’s work in the postwar period, this shift was reflective of what Mumford perceived to be humanity’s darkening prospects. Earlier hopes that the destructive power of the machine would be productively harnessed to renew life seemed foolish in the shadows of mushroom clouds.

Mumford’s horror at the atomic bomb, and at the nuclear arms race, played out alongside the postwar economic boom that saw a host of new consumer technologies rolling off the assembly line and into people’s homes. Mumford sought to raise the question of what types of society these new machines were producing, noting in his essay “Technics and the Future of Western Civilization” that “unlimited profit and unlimited power can no longer be the determining elements in technics if our civilization as a whole is to be saved.” Surveying the technological landscape of the mid-20th century, Mumford was particularly worried about the development of massive technological systems that reduced human beings to little more than parts of their machinery. In thinking about such systems, Mumford was concerned with the nuclear weapons apparatus, but he was also directing his critical gaze towards the emergence of “the thinking machine,” as he put it in The Transformations of Man, which had created “a new object of worship: a cybernetic god” — the computer.

Which brings us back to the bribe.

The concept of the bribe did not appear in isolation. It was an attempt to answer a question raised by other theorizing Mumford was doing at the time. In assessing the growing power of complex technological systems, Mumford sought the proper terms with which to discuss these systems. He began talking about a split between “authoritarian” and “democratic” types of technologies. The term “authoritarian” was affixed to complex, centralized systems, over which individual humans could exert little control, while the term “democratic” was reserved for smaller scale systems that could be controlled by individuals. A key factor in the power of “authoritarian” technologies was that they steadily worked to eliminate alternatives to themselves.

Provocative though it surely was, this juxtaposition was subsumed into Mumford’s concept of the “megamachine.” With the “megamachine,” Mumford was attempting to put a name to the combination of bureaucratic, technical, military, political, and economic forces that combined to exert control through advanced technological means. While Mumford saw evidence of early gestures towards the “megamachine” throughout history, he saw that the technological developments of his day had provided the means by which the megamachine could finally turn humanity into “a passive, purposeless, machine conditioned animal.”

The bribe was primarily about incorporating people into a world that complex technological systems were remaking in their own image

Whereas rulers had long fantasized about observing every act of the populace, the computer actually made this possible; whereas rulers had dreamt of harnessing the destructive power of the deities, nuclear bombs now gave them this might. The megamachine, in Mumford’s estimation, seeks to turn all people, whether they realize it or not, into cogs whose every action serve only to further entrench the power of the megamachine. It is often easier to describe an intimidating dictatorial system than it is to explain why people go along with it. Thus, the bribe.

Those ready to accept the “authoritarian” technologies of the megamachine were “granted all the perquisites, privileges, seductions, and pleasures of the affluent society,” he wrote in The Pentagon of Power, such that they could look around themselves and genuinely conclude that they were enjoying “a higher standard of material culture” than any society had ever known. A deluge of luxuries and comforts were being made available by advances in the machinery of mass production, thereby displacing attention that had once been focused on demands around essential human needs. The bribe offered a share in the scientific and technological “progress” that certain populations were commonly seeing extolled in the popular media, and encouraged them to see further scientific and technological progress as essential to improving their own lives and conditions. The offer appeared to be quite the “generous bargain,” and insofar as some tradeoffs were involved — including the ability to live outside of this technical system — these did not seem like “a horrid sacrifice but as a highly desirable fulfillment.” The recipients of the bribe were encouraged to believe that “by accepting” this cascade of products and devices, “every human problem will be solved for them.” One could enjoy all the benefits of automation, so long as one did not mind being reduced to the role of an automaton.

Yet Mumford was not merely being sarcastic in describing the bribe as “generous” and “magnificent.” Any attempt to wrestle with the metastasizing power of the “megamachine” required recognizing that much of what it offered truly did appear impressive and beneficial. Writing in 1970, Mumford rattled off a list of some of the bribes of his time, a list that included refrigerators, private motor cars, planes, telephones, television sets, electrically driven washing machines, and the computer. Mumford emphasized that these new products should not “be arbitrarily disparaged or neglected, still less rejected out of hand.” After all, Mumford was not a reclusive ascetic hermit — he rode in cars, flew on planes, and talked with friends on the telephone. In denouncing the bribe, Mumford was not simply blasting this or that particular machine. He was questioning the ways that particular machines were used to incorporate people into a much larger technical system. What at first could seem like a “generous bargain” had a tendency to eventually feel like more of a raw deal, and once the initial excitement around a new gadget had vanished, a person all-too-often found that the new machine had not in fact solved “every human problem.”

The offer appeared as a “generous bargain,” and its tradeoff — the ability to live outside of this technical system — not “a horrid sacrifice but a highly desirable fulfillment”

That so many had come to believe that advances in science and technology would save them was in keeping with what Mumford described in his 1975 essay “Prologue to Our Time” as “the ultimate religion of our seemingly rational age — the Myth of the Machine.” A religion at the core of which was a faith not merely in the idea of progress, but specifically the belief that technological progress was synonymous with every other sort of beneficial progress. The all-seeing computer came to replace the all-seeing god, the earth-destroying wrath of god became the nuclear missile, and the high priesthood who interpreted the word of god for their flock became the bureaucrats and technical professionals who tended the sacred machines. Thus, accepting the bribe became a technological form of accepting holy communion, and those who suggested that these machines were only so many more false idols found themselves tarred as heretics.

While specific technologies needed to be evaluated on their individual merits, in warning of the allure of the bribe, Mumford questioned not the devices themselves but the system that had produced them. And while that system might make a good show of talking about all of the ways its newest doodad would address human needs, the greater need being met was not the people’s, but the system’s need to entrench its own power. In rejecting the bribe, Mumford, in The Pentagon of Power, urged “a formal recognition of the fact that mechanical gains have often been achieved at great social losses, and that before one accepts unconditionally the gifts that megatechnics offers one must examine the accompanying deficits and decide whether the benefits justify them: and if immediately desirable, whether they are actually so in the long term.”

To think of our myriad devices (and the platforms we use them to access) as bribes, and to think of ourselves as having been bribed, can be quite disconcerting. And yet the term may still provide us with a useful tool for making sense of today’s technological world. The bribe does not demand that we deny the various ways particular devices have genuinely benefitted our lives, but it asks us to recognize that these devices were not made available to us because their creators are beneficent. In the present moment it seems that many people are increasingly feeling that the deal they entered into with today’s technological forces may not have really been such a fair one. Nevertheless, even as one might bristle at the latest reports of this or that tech company’s malfeasance, our societies have become so reliant on some of these devices, platforms, and systems that dreaming of shutting them off seems like a pure fantasy — and seeing as there are some real benefits, many of us do not really want to shut these systems down.

Too often, technology winds up supplying its users with new luxuries that eventually become new necessities

In theorizing the bribe, Mumford had warned that after enough people accept it, “no other choices will remain.” Thus we might balk at Facebook’s latest misdeeds and cheer for the idea that some regulation might be coming, while glumly recognizing that under the guise of making it easy to connect with friends and family, Facebook has managed to become essential infrastructure for many people around the world. We might grumble at the way our smartphones, which seemed so wondrous at first, have intruded into every living moment (waking and sleeping), and yet recognize that, at this point, to go without a smartphone is perhaps more of a sign of privilege than to have a smartphone. Among the evidence that contemporary technological advancements can be harnessed to ensure that all are supplied with the necessities of life, it is clear that, too often, technology winds up supplying its users with new luxuries that eventually become new necessities. Where once access to a computer and the internet were amenities, for many people today, they have become essential.

Even as yesterday’s bribes become today’s commonalities, a steady flow of new bribes is made available to preserve our loyalty. There are smartphones with bigger screens and better cameras, virtual reality headsets, NFTs, smart glasses, self-driving cars, personal robots, a promised land of infinite apps, artificial intelligence, and the list goes on — new bribes for the new moment. As soon as it becomes incontrovertible that the last crop of technologies promising to solve “every human problem” has created many new problems, we are offered a new crop of technologies promised to really solve “every human problem,” including all of the ones created by the previous crop of technologies. Once you start looking for them, you can see technological bribes everywhere. And once you stop mulling over the potential benefits on offer, you can begin to see the risks and harms lurking just behind the shiny façade.

Despite the ominous tones in which he often wrote, Mumford did not believe that we were doomed to become automatons. He retained a stubborn hope throughout his life that the sleepers could awaken, and that all hands could save the sinking ship. While writing extensively about technology, time and again he emphasized that what needed to be confronted was not so much the machines themselves as the ideology that builds up around them and turns them into objects of fealty and worship. As he pithily put it in Art and Technics, “If you fall in love with a machine there is something wrong with your love-life. If you worship a machine there is something wrong with your religion.”

It is not a good thing to be accepting bribes, but it’s even worse to think of those bribes as just friendly gifts.