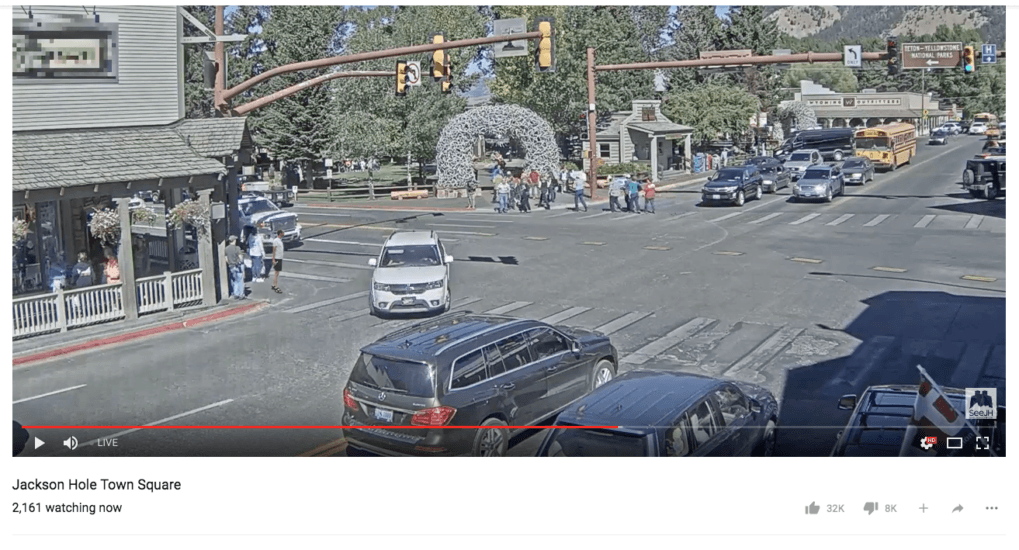

This feed, from a traffic surveillance camera in Jackson, Wyoming, a small town in the Grand Teton Mountains, has been recently memeified. That no one is entirely sure why it has become a meme is a key component to why it has become a meme. Thousands of viewers have been dropping in and out on the livestream on YouTube, supplying Twitch-style running commentary to the non-action.

Why are they watching? Because there is nothing to see. There is a minimum of “message” to the stream, so viewers get to consume mediation in the abstract. In an email exchange we had about the feed, Nathan argued that because the ostensible content of the stream is so banal, it allows viewers to see past it and experience pure “watching-togetherness,” which the mundane level of the chat amplifies and reinforces. The stream lacks distinctive content and the comments equally lack substance: By not being clever or funny or informative, they can be pure reaction, in the moment, together. And the stream moves so fast, anything typed is less expression than mere impression. People just mostly signal that they too see what the others watching from wherever are seeing. At Fusion, Ethan Chiel labeled this “simultaneity porn.”

It’s pleasurable to feel like you are there at the birth of a meme. There is a frisson of serendipity and randomness, of arbitrariness gathering momentum toward sense. You are patient minus one for something viral. Watching the chat on this live stream, joining in, you can be present as meme creation goes not only viral but fractal, as every little thing that happens onscreen is instantly pushed as a mini-meme within a meme.

The chat lets viewers register an effortless co-presence that carries with it no reciprocal responsibilities, no sort of mutual recognition beyond the level of “red truck!” But more interesting is the way the feed concatenates this togetherness with the encroaching practices of surveillance.

We are used to singling ourselves out in social media, attaching our identity to content we hope will help make us stand out or show how clever or considerate or caring we are. We are also getting used to ubiquitous ambient surveillance, a feeling that we are always on camera, always being tracked, always having a profile compiled about us as individuals. The Jackson Hole livestream counters both of these tendencies, allowing us to assume a sort of god view as a collective subject, becoming the “they” who does the observing instead of the “me” being seen.

The chat subsumes individual voices in a babbling group chat in which nothing is ever said but a togetherness is sustained. And the fact that there is nothing much to see assures that there won’t be much disagreement among those watching. The sheer banality helps establish the transcendent, transindividual perspective. It builds in-group solidarity without the bother of shared values, and offers the impression that the creativity, belonging, and participation that come from in groups — the inside jokes, the privileged understandings — can be spontaneously and apolitically available.

Moreover, there is catharsis in watching something so apparently neutral. Nathan suggested that it’s a relief to find a socially acceptable location from which to be a watcher, where a chorus of voices confirms that the surveillance is noncreepy, nonharmful. It disperses some of the surveillant anxiety Kate Crawford describes here: Any data that’s collected seems to demand an anxious craving for even more data to make it understandable, in a never-ending process of ever more granular data collection. But there is nothing to understand about the Jackson Hole feed. It’s just watchable.

The banality that the stream currently typifies (or maybe typified a few weeks ago) can be liberating, but it is also unstable. It becomes too conspicuous — it becomes interesting for being uninteresting. Then the way it divides us into those who get it and those who don’t becomes foregrounded, and surveillant anxiety returns. Do I even really know what’s going on? Maybe they’re laughing at me.

The “red truck is life” until everyone understands what that means. Then it becomes a marker of social death — of who, like me, didn’t get it until it was too late.