With every heavy travel season comes another round of calls to privatize or kill the Transportation Security Agency. Hatred for the hapless agency seems to have reached an all-time-high this summer. It’s not just the record-long wait times. In April, the New York Times reported that the TSA routinely retaliates against employees who point out security lapses to their superiors. In May, the agency fired its head of security operations, American Airlines publicly shamed the TSA for causing thousands of passengers to miss their flights, and a Florida congressman published a guidebook, TSA for Dummies, to document the agency’s “meltdowns” for the uninitiated.

But while government audits and reports continue to paint the agency as an unequivocal failure, those numbers are irrelevant to the metrics that govern the agency’s online reputation. With over 400,000 followers, the TSA’s Instagram account wages a curious, uphill public relations campaign — one that bears an inverse relationship to the agency’s unpopularity offline. Last year Rolling Stone ranked the winsome, faux-naive “@TSA” the fourth best account to follow.

On the agency’s official Instagram, objects that slow down security lines transform into hilarious artifacts, and the nameless canine agents you’re forbidden to touch in real life appear as cuddly characters. Whereas interactions with the TSA were once limited to sterile airport settings, we can now continuously interface with the agency’s casual personality on our phones anytime, anywhere. All we have to do is scroll through the feed’s amateur photography of confiscated carry-on items, sorted by the self-congratulatory hashtag #TSAGoodCatch.

The majority of those “good catches” are of guns. Some are pictured in isolation against wood and laminate surfaces, like family heirlooms for sale on eBay. Occasionally, a large Photoshopped array of hundreds of confiscated firearms will be uploaded, in an apparent attempt to convey the extent of the firearm-smuggling problem and the determination with which travelers stick to their guns.

There are many cane swords — so many that the agency recommends you pull the handle of your cane to see if you may have purchased one by accident

As a respite from the gun show, adorable snapshots of the agency’s dogs punctuate the feed at regular intervals, introducing us to the security state’s mascots. These canine interludes, hashtagged #WorkingDogs and #DogsofInstagram, show such “good boys” and “good girls” as Botka, Doc, Guiness, Fable, Spike, Mojo, Yoshi, Tarzan, Toro, True, Woody, Missy, Oonda (named after a 9/11 victim), Folti (retired after 10 years of service), Screech, Simba, and “don’t let his name fool you” Baby. I could go on. Some lucky pups are even Photoshopped onto trading cards, like all-star athletes.

Aside from guns and dogs, the feed largely consists of bizarre and dangerous items, including images of every sort of knife imaginable: swords and throwing stars, switchblades and pocket knives, a three-piece set of neon green “faux blood adorned” machetes. There are cherry-red hacksaws, cherry-red brass knuckles with pop-out blades, and rainbow-tinted daggers, carved sharply on both ends. For the cosplay fan, Batman-shaped throwing blades and razor-blade stars (tagged #Krull in a shout-out to the 1980s sci-fi film) abound.

Concealed blades are discovered in black combs, in pink combs, in pens, in the plush of neck pillows, on thighs, under bras, wedged into a homemade enchilada. There are many cane swords — so many that the agency recommends you pull the handle of your cane to see if you may have purchased one by accident. Multipurpose tools have been slipped under the soles of shoes, stuffed in bottles of pills, slotted into a hard drive, and buried within a metal pan of what appears to be a half-eaten casserole. The casserole traveler’s intentions were “delicious, not malicious,” @TSA confirmed.

Also on display are ingenious or idiotic stashes of drugs. In the accompanying captions, the agency comes across like a Cool Dad, explaining that the TSA would never explicitly look for drugs but is, unfortunately, required to report them when discovered. Which they are — in the battery compartments of computer mice, in false-bottomed shaving cream or beverage cans, in tubs of peanut butter, and so on.

Of course, not everything the TSA confiscates gets posted. The agency spares us visual documentation of the millions of bottles of water and other larger-than-three-ounce vessels of liquid it captures. Scrolling through the hundreds of squares, a subtle but forceful hierarchy begins to emerge. The more singular the catch, the more popular it becomes. A stun gun disguised as rhinestone-spangled lipstick case, for instance, garners more likes than a can of bear mace. The most ingenious of these #catches weave surprise, stealth, and traveler stupidity into a single object: consider the eight-inch double-edged knife “artfully concealed” in an Eiffel Tower replica statue; the seven small snakes wrapped in nylon stockings, dangling under a traveler’s pants; or, my favorite, the five dead endangered sea horses floating in an oversize bottle of VSOP. The alcohol-doused animals represent a two-in-one prohibition, as does the bag of cocaine hidden in a water bottle with more than three ounces of liquid, and the grenade-shaped weed grinder. “Anything resembling a grenade is prohibited in both carry-on and checked baggage,” noted @TSA. “Especially if it’s a grenade shaped grinder with marijuana inside.”

Despite the occasional oddities, flipping through @TSA can quickly become a familiar ritual: gun, gun, throwing star. The unceasing repetition of forms on the feed offers a sense of security, however false. The recurrence of threats averted makes it seem as though they can be known, even anticipated. But this soothing logic easily gives way to its opposite: that the threats on view are not contained but endlessly regenerative and, therefore, unstoppable. “Is there an Instagram account,” one user asked, “where people post what they got through security with because you didn’t catch it?”

This question hints at the larger ambiguity underlying the account. Does @TSA display dangers contained or dangers to come? It’s an unanswerable question by design. For homeland security to justify its function, every threat must be at once under control and uncontrollable.

The #TSAGoodCatch hashtag uncritically celebrates the agency’s acumen, but it reads less like a humblebrag and more like a desperate plea against dire odds. It’s impossible to understand TSA’s social media personality apart from the agency’s material reputation for inefficiency and waste. The winking friendliness and whimsy of @TSA seems tailored to help us forget how unpopular the agency has been since the beginning. The month after the attacks of 9/11, the U.S. Senate cast a rare unanimous vote in favor of the federal government taking over airport security from private contractors — a decision that nearly everybody has been unhappy with ever since.

Among the TSA’s fiercest critics is Bruce Schneier, a computer-security expert who seems to take an almost perverse satisfaction in the agency’s flaws, just as Sherlock Holmes relished the mishaps of London police. In 2003, Schneier coined the term “security theater” to describe the TSA’s knack for providing a psychological veneer of safety in lieu of instituting tested security measures. By offering procedures to make travelers feel secure, he argues, the agency creates “audience-participation dramas” for “movie-plot threats.” “Focusing on specific threats like shoe bombs or snow-globe bombs simply induces the bad guys to do something else,” he explained to Vanity Fair in 2011. “You end up spending a lot on the screening and you haven’t reduced the total threat.”

One early TSA posting read: #StunGun #disguised as a pack of #cigarettes discovered at #Cleveland — #cle #stun #stunguns #tazer #tazers #shock #shocking #travel #aviation #tsa #instatsa #tsablogteam #tsagram #gov20 #gov. None of these hashtags would catch on

What little data that has been released on the TSA’s activities over the past decade confirms Schneier’s analysis. A 2010 Government Accountability Office report found that the TSA’s $200 million investment in a secret program to detect terrorist behavior through facial tics and other “tells” failed to detect any terrorists, including at least a dozen individuals later involved in terrorism cases. This was unrelated to the discovery, in 2015, that 73 of the agency’s own workers were on the U.S. government’s no-fly list.

Each year brings new failures. A 2011 congressional report found that the agency had permitted 25,000 security breaches in the past decade. In 2012, a TSA official admitted that no arrests could be attributed to the implementation of whole-body scanners. Three years later, the quarter-billion-dollar body-scanning equipment was unveiled as an essentially decorative set piece: A security audit revealed that the scanners failed to discover weapons and explosives 95 percent of the time. This led the Washington Post to wonder why the agency celebrated 2014 as “a great year” on its blog, where it boasted of an average seizure rate of six firearms a day. “Americans aren’t sure if that’s a measure of success or a colossal failure,” Senator Ben Sasse, a Republican from Nebraska, noted.

In the midst of this perpetual public relations disaster, @TSA was established, on June 30, 2013, by “Blogger Bob” Burns. Though it would eventually find its charismatic voice, the Instagram account’s first post reveals a less than confident grasp of the medium: “#Fireworks don’t fly. (On planes) #july4 #travel #instatsa #firstpost #aviation http://1.usa.gov/16xLT7a.”

Other early posts wielded hashtags as gnomic apothegms. One early, pound-heavy posting read: “tsa#StunGun #disguised as a pack of #cigarettes discovered at #Cleveland — #cle #stun #stunguns #tazer #tazers #shock #shocking #travel #aviation #tsa #instatsa #tsablogteam #tsagram #instagood #instacool #webstagram #instagramhub #photo #gov20 #gov #all_shots.” None of these hashtags would catch on.

The house style that eventually prevailed on @TSA — equal parts playful, pithy, and paternalistic — makes amends for the agency’s paranoid mindset. Its winking cleverness distracts us from the agency’s uncool job of enforcing uncool rules: “This brush dagger was discovered in a carry-on bag at the #SanFrancisco International Airport. Familiarizing yourself with the prohibited items list prior to flying can prevent hairy situations.” Cue the laugh track, and the likes.

The TSA is hardly alone among giant, faceless organizations in its adoption of a knowing, teen-like tone. Writing in the New Inquiry, Kate Losse dissects the rise of the “insouciant, lowercase voice” of corporate social media accounts. Losse observes that “a traditional corporate entity, which has historically had no direct ‘voice,’ suddenly distilling itself into an eccentric, devil-may-care character is instantly affecting, precisely because of how uncanny, even creepy, it is.” The absurdist attempts at intimacy are at once disarming and meta.

When the agency makes its crude collages, cramming as many gun photos as possible into the frame of a single post, the effect is more horror vacui than rule of thirds

The TSA’s account similarly ingratiates with knowing irony. The joke, for once, is not on the hapless agency, but on the clueless passengers who try to bring stupid stuff onto planes. The switch is deliberate. As Blogger Bob revealed to Wired in 2014, “You change it from people complaining about TSA to people saying, ‘Wow look what TSA found, I can’t believe someone would try to come through with this.’ ”

In many respects, the ironized propaganda works: @TSA humanizes the tedious work the agents perform. As I meticulously logged the account’s activity, I started to understand how tiring — and difficult — the actual work of managing security checkpoints could be. At the same time, I started to wonder what an “unofficial” account of the agency’s activities would look like.

I didn’t have to look very far. This summer, the industry lobbying group Airlines for America launched a social media campaign to harness the season’s widespread frustration at the agency’s epic wait times. Encouraging flyers to tweet and Instagram photos of long security lines, the #iHateTheWait campaign counteracts @TSA’s rosy pictures, unleashing a raw, populist portrait from the other side of the scanners. @TSA has yet to embrace this hashtag.

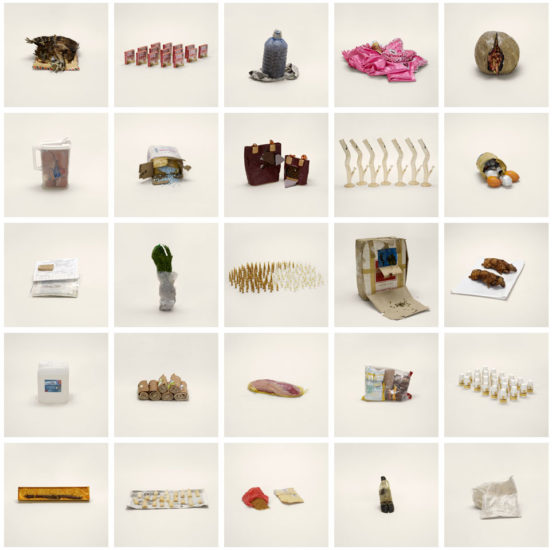

TSA agents weren’t the first photographers to embark on a massive catalog of objects confiscated by airport security. A few years before the agency’s photographic forays, artist Taryn Simon spent five days at New York City’s John F. Kennedy Airport, photographing the objects passing through both Customs and Border Protections and the U.S. Postal Service International Mail Facility. The 1,075 photographs in her Contraband series, indexed and alphabetized according to the descriptions provided by agents, suggest an alternate archive to the @TSA’s — not least because her content is explicitly international in its provenance. The objects Simon’s camera most frequently captures are not handguns but pills, fruit, handbags, and other counterfeit luxury items. Both threats and desires are on view.

Simon photographs these confiscated items against what curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist describes as “an unchanging gray backdrop, the color of administration and neutrality.” Where the TSA’s ephemeral scroll renders its items disposable, the static portraits presented in Contraband appear monumental, like a still life or a mug shot. Art critics like Obrist praised Contraband for capturing the banal, impersonal uniformity of a bureaucratic aesthetic, but the TSA’s aesthetic, as expressed through social media, has proved anything but administrative. The TSA’s Instagram feed favors eclecticism over discipline: Various filters, formats, qualities, and image sizes proliferate. When the agency makes its crude collages, cramming as many gun photos as possible into the frame of a single post, the effect is more horror vacui than rule of thirds.

Unlike the gray austerity of Contraband, the vibes are chummy, goofy. Adding a social media twist to the “Wanted” poster, the TSA account makes the act of self-surveillance seem fun, friendly, folksy. The point isn’t simply to learn the rules, it’s to heart them. The agency may be despised in real life, but its activities are liked thousands of times a day online.

Most thing-based Instagram accounts — for food, yoga, beaches — entice us to vicariously consume lifestyles and fantasies, but @TSA’s viral exhibitionism has the opposite function: to steel ourselves against making the same mistakes as those whose possessions are on view. @TSA instructs through these object lessons.

In the 19th century, criminal-identification photographs were “designed quite literally to facilitate the arrest of their referent,” writes critic Allan Sekula. The invention of the modern criminal constructed at the same time the figure of the law-abiding citizen, who distinguished themselves from photographs of deviancy.

While retrospective #TSAGoodCatch images don’t aid agents with the identification of suspects or objects, they do help the average traveler learn to be a better, safer citizen. @TSA is not aspirational but proscriptive. Just like the #WorkingDogs of the #TSAInstagram, we can become good boys and good girls, too, if only we catch ourselves before they catch us.