It’s easy to recognize when surveillance is deployed for coercion and control. It might fit the well-rehearsed warnings about Big Brother or the panopticon, appearing as a top-down system imposed on populations by authorities (China’s use of facial recognition to oppress Uighurs, or U.S. law enforcement’s use of license plate readers to indiscriminately track drivers, etc.), or it might be some egregious use of stalkerware deployed by someone like an abusive partner.

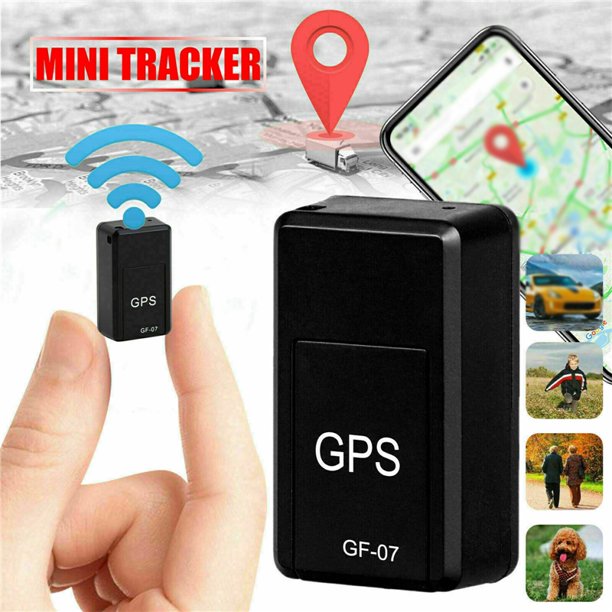

But often, surveillance comes packaged not as coercion but care. At the personal, consumer level, it might appear as a baby monitor or a networked camera doorbell, a GPS tracker or a fitness wearable. Institutionally, it could appear as an educational or a medical technology: a remote-proctoring system or new kinds of cancer screenings, learning analytics or a mental-health app provided by your employer.

It can be uncomfortable to use the word surveillance to describe these kinds of situations; its negative connotations would seem to align a caregiver with authoritarian modes of control. But in its broadest sense, surveillance — defined by scholar David Lyon as “the focused, systematic and routine attention to personal details for the purposes of influence, management, protection or direction” — seems to embrace both care and control; it can be both “watching over” and “watching out for.” Protection, direction, influence, and even management can easily be perceived as closely aligned to concerns of care, if not inseparable from them. Be it for our children, partners, or property, surveillance promises that we can gain peace of mind or become more conscientious — that we can think of ourselves as better caregivers.

Protection, direction, influence, and even management can easily be perceived as closely aligned to concerns of care, if not inseparable from them

But do those promises hold water? At what point does that desire to be a better caregiver come into conflict with the realities of bettering our environment, society, or loved ones? After all, the implication of surveillance is to always give insight and control to those with power, often reinforcing racist, ableist, colonialist, and heteronormative conditions. As Chris Gilliard has detailed, the most vulnerable bear the brunt of surveillance, as they are more insistently targeted and harmful new techniques are applied to them first.

What prevents good intentions from sliding over into manipulation? How can we be sure that our norms and standards of care serve the best interests of who we are trying to care for, especially when those “best interests” can conflict with their stated wishes? How can we know when particular ends of surveillance might justify the means, or when the means have become an end in themselves? The language of care can seem to answer these questions by dismissing them. That is, it can be used to account for, rationalize, and promote surveillance technologies that ultimately cause vastly more harm than good. This is the weaponization of care.

Our worries are buttons that are easily pushed. We can see this weaponization at play in advertising: “Night and day, never a second away” pledges an ad for a baby-monitor camera, which touts itself as “ideal for new moms.” The surveillance doorbell Ring and its associated Neighbors app have a whole section of their blog dedicated to heartwarming stories, one of which proclaims, “No matter where you are, with Ring, you are always close to people who mean the most.” Weaponized care also admonishes you in that “if you’re responsible for a child or manage an employee, you have a duty to know,” as FlexiSPY claims in selling its device-monitoring software. Even devices like magnetic GPS trackers, designed to be planted on the undersides of cars to track someone’s movements secretly, are marketed with a rhetoric of concern, diligence, and care: “This tool can record your love for others.”

The examples are nearly endless. To listen to the advertising and the sales reps, you would be more than remiss, you would be cruel and callous, if you did not use these tools once they are available. Never mind that they often don’t work and may not be much more than fronts for data collection, if not worse. In a previous Real Life essay, Hannah Zeavin discussed how parenting technologies help routinize broader kinds of state surveillance.

Time and time again, companies embed the language of care in their rhetoric around new surveillance technologies — particularly when they hope to normalize them in more consequential and intimate parts of our lives. Through inspecting theories of care and how we might think of care itself as a larger construct — something that occurs at a collective rather than individual household level — we can shine some light on how and why care is so readily weaponized and perhaps find ways to disrupt this process.

One place to start is the frequently gendered distinction of care ethics, posited by Carol Gilligan and Nel Noddings, from traditional virtue ethics. Noddings drew the distinction between virtuous care, or “caring about,” and relational care, or “caring for.” Virtuous care, often gendered as male, orients concern to a theoretical set of universal rights and wrongs; whereas relational care, often depicted as female, is seen as more contingent, intimate, and situational. Virtuous care is a matter of acting out of a caring about general ideas or theories. Relational care, on the other hand, has concern for particular people, pets, spaces, places or other subjects and takes into account a network of various possible moral outcomes to work toward the best possible result for the subject of care. Caring about the idea of children’s well-being in a general or global sense, perhaps giving a donation or purchasing a particularly sponsored kind of product, is different than caring for a child of your own or even performing that care by volunteering to work with underprivileged children.

The significance here is that relational care has a history of being devalued and held under suspicion relative to virtuous care. Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg, who proposed an influential theory of moral development in the mid-20th century, claimed that women were less morally developed than men because they weighted relational care more highly in their reasoning when responding to Kohlberg’s hypothetical situations. In one example, two children, a boy and a girl, were asked to consider the so-called Heinz dilemma, a thought experiment about a man who has no way to obtain a life-saving drug for his wife but to steal it. Kohlberg argued that the boy, in answering that the man was right to steal the drug since a life-or-death matter had greater moral justification than protecting property rights, was morally superior to the girl, who answered that the theft would be wrong because if the man were caught, his wife would be in an even more precarious position. Carol Gilligan, who assisted with his research, famously rejected Kohlberg’s view, arguing that the girl’s relational view of ethics was not “lower” but instead simply came from “a different voice” in emphasizing relational over virtuous care. Gilligan resisted the idea that this dichotomy between the two ways of caring were inherently gendered and was adamant that the distinction was thematic. Still, these gendered stereotypes and histories are hard to shake; in identifying the weaponization of care, we can use them as a tool.

This stereotypical binary view of caring is problematic, but its assumptions remain in play in how care is weaponized, with the two forms of care pointing to two distinct rhetorical strategies. Some surveillance technologies are sold with references to virtuous care, as when city-wide video surveillance systems like Detroit’s Project Green Light are touted through reference to a universalized idea of justice. Others make appeals to relational care, positioning surveillance as a way to make customers better, more informed, and loving caregivers, as when “elder monitoring solutions” like Lorex play to the busy lives of adult children. “Give yourself peace of mind,” the company urges, with products that provide not just video and audio surveillance but also motion detection and infrared night vision.

Caring for the ones we love is among the strongest of human instincts, so surveillance companies seize on this as a vulnerability

These contrasting strategies both ultimately draw their energy from positing their form of care as superior or more situationally appropriate than the other, as though they could be cleanly separated and weren’t simultaneous in practice. This mirrors the idea that surveillance as care can be separated from surveillance as control — that you can embrace one without taking on implications of the other.

The two different approaches align with a distinction Luke Stark and Karen Levy outline in their 2018 paper “The Surveillant Consumer” between the “consumer-as-manager” and the “consumer-as-observer” — two distinct subject positions structured by tech company rhetoric about surveillance. The “consumer-as-manager” fits with appeals to virtuous care, seen as opposed and superior to relational care: Consumers are recruited, for example, into supplying ratings for low-wage gig-platform workers, invoking a universal ideal of service as well as exploiting the consumer’s desire for control and convenience. By giving consumers a sense of authority and voice, food delivery tracking apps, rideshare services, and other similar apps foreground consumers’ “caring about” the quality of service over “caring for” the workers performing the service and the conditions they face — even as stories about the perils of gig work are mounting.

Meanwhile, the “consumer-as-observer” frame centers relational care, playing on how surveillance can supposedly enhance our most intimate relationships. Stark and Levy write:

In this paradigm, surveillance is constructed as being normatively essential to duties of care across the lifecycle. Watching and monitoring are construed not merely as the rights of a responsible parent, dutiful romantic partner, or loving child — but as obligations inherent in such roles.

Caring for the ones we love is among the strongest of human instincts, so surveillance companies seize on this as a vulnerability. Hence a product like Life 360, which offers constant location tracking, route mapping, and driving-habit analytics, can promise to “bring families closer” rather than drive them apart, consequences that Angela Lashbrook details in this One/Zero piece. As technologies create ever more nuanced ways of surveilling, the line defining what is reasonable and what is not becomes blurred. The language of care is deployed to justify greater and greater intrusions.

Because appeals to virtuous and relational care so easily play to stereotypical ideas of masculine and feminine, the weaponization of care plays out unevenly and serves to reinforce these deeply flawed ideas. Their connection to different ways of caring is used to goad people into adopting unethical surveillance technology based on how they may aspire to identify with these norms: To be sufficiently male or female one needs to be able to demonstrate a commitment to keep watch in a particular kind of way.

These same stereotypes feed into how care is weaponized in vocational fields that are also perceived as gendered. Education, for example, is riddled with surveillance technologies, as Audrey Watters details here — everything from learning analytics to plagiarism checkers to remote proctoring systems. Such surveillance can easily be rationalized as relational care when it pertains to primary schools, whose workforce is typically presumed to be female, and caring for the children. Class DoJo, for instance, promises to “bring every family into your classroom, build a positive culture, and give students a voice.” Yet the software, which aims to connect parents to the nuanced behavior of their children throughout the school day, has been widely criticized for its data privacy practices, for how it makes marginalized students more vulnerable to teacher bias, and for its shame-based behaviorist approach to class discipline.

By contrast, virtuous care is evoked to promote remote proctoring systems, which are pitched as caring about protecting ideas of rigor and academic integrity. Students are framed as intrinsically suspicious (much as workers were framed in Stark and Levy’s “consumer-as-manager” framework). ProctorU, for instance, claims its technology will help school officials “protect [their] creditability” and “preserve the value of [their] program.” But these technologies cannot assure that cheating will not happen, as Gabriel Geiger details in this Vice piece. Yet the harms to students are manifest, including disparities in treatment according to race and ability, increased stress and anxiety, privacy threats, and data security issues, not to mention the broader harms that stem from the normalization of surveillance in everyday life through its use in an educational setting.

To be sufficiently male or female one needs to be able to demonstrate a commitment to keep watch in a particular way. The weaponization of care reinforces this deeply flawed idea

Health care, like education, is another care-centered field, perceived to be gendered, where we see surveillance tools; in fact, much of health care is surveilling for disease. The collection tools go way beyond cameras and microphones, and the data obtained by them and stored in health records are some of the most sensitive that can be obtained. Because the storage of these records is highly regulated, as is medical-related advertising, the weaponization of medical care to promote exploitive surveillance might seem under control. But the possibilities are there, as the short film Blaxites explores in a fictionalized scenario (written by Nehal El-Hadi, directed by Josh Lyon, and produced by sava saheli singh as part of the Screening Surveillance project). The main character, Jai, is a student who suffers from anxiety and is prescribed a controlled drug to manage it. This puts Jai under a closer medical gaze, and she finds herself subjected to both virtuous and relational care that goes wrong. Her prescribing doctor, acting out of an overactive sense of virtuous care, shocks Jai by revealing how they monitor her social media. “We make it a policy to keep an eye on our patients,” the doctor tells her. “We just want to make sure you’re not doing any harm to yourself.” Jai does not fare much better with her best friend’s relational care: He tries to help by connecting Jai to an underground network that can get her the drug only to find that the hospital can track its traces through a hospital-issued wearable. His relational care fails further when she is unable to reach him after he deletes all social media to try to escape the encroaching surveillance that has ensnared her.

Fiction can help us to realize the complexities of weaponized health care, but we certainly can see evidence of harm and how these tools are justified and rationalized outside fiction. In an article for Science, Ruha Benjamin analyzed a study that showed how one of the largest proprietary algorithms meant to improve the distribution of care through data analysis put Black patients in danger because of how it classified costs and risks. In using cost as a proxy for the need for care, the tool assumed that care is distributed equally, but that simply is not true. Yet one can imagine how this product might have been sold to hospital administrators: cost savings (virtuous care) and better patient outcomes (relational care). Benjamin notes how the use of such tools have become more commonplace due to pressures from the Affordable Care Act for hospitals to minimize spending – caring about cost-savings. But this algorithm also attempted to care for patients by identifying those who needed more attention, only to fail because of a myopic view of who those patients were.

Weaponized care is not a monolith, and we must be attentive to how it can be wielded in different directions and for different purposes. Most insidiously, it seizes upon how care is necessary and essential for our social lives. But it can be weaponized in a different way: As Audre Lorde wrote, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” Here Lorde rejects gendered ideas of care and posits a different approach to its weaponization: not as a way to sell harmful surveillance technology but to protect herself from overextension and despair in the face of disease and the stigmas attached to several overlapping marginalized identities. Realizing and recognizing that care can be used as a weapon against the interests of our communities, our loved ones, and even ourselves is a step toward respecting this powerful construct.