The ghost appeared in flickers, a damaged reel of film, revealing its pale scars to the machinery that gouged them. As a Cambridge student during the 1920s, T. C. Lethbridge recognized the silent specter by its unfashionable top hat. He later became Keeper of Anglo-Saxon Antiquities at the same university, steering his archaeology towards paranormal oddities until he’d deserted academia entirely. Lethbridge took mystic guidance from the swings of a dowsing pendulum; he convinced himself that the witch trials had purged a secret pagan underground.

In the 1961 book Ghost and Ghoul, his attempt to describe otherworldly phenomena in scientific terms, Lethbridge recalled hauntings like his Cambridge visitor: “The whole production, in each case, was exactly comparable to a television scene. There was the same curious lack of atmosphere and the same general gray drabness … The figures were pictures projected by somebody other than myself and I was nothing more than the receiving set.”

The spirit-media analogy still resonates, because both violate the linear model of time

Lethbridge believed that haunted places served as recording devices for emotional outbursts, broadcast through the aether to anyone whose wavelength quivered. The ghosts themselves had no agenda: they were mental figments, psychic TV. Hearing voices from a strange machine, many Victorians must have twitched with superstition. Lethbridge inverted that impulse, and sought to understand hauntings as primeval communication technology. In Ghost and Ghoul he argued that “the supernatural of one generation becomes the natural of the next one.”

These theories were popularized by Nigel Kneale’s film The Stone Tape, a classic of zero-budget ’70s horror, where the R&D team for an electronics company, working at a country manor, discovers the building is somehow replaying a servant girl’s agonized death. Too late, they realize that the house’s foundations date back many hundreds of years — before Christianity, before England — and her disembodied scream was only dubbed over some ancient atrocity. Trying to find the source of this evil noise, the heroine’s cries end up harmonizing with its other victims. Audio cassettes were still novel then, and The Stone Tape uses their peculiar features, like the capacity for re-recording, to imagine a ghost skulking around the subconscious. Here there is no murderer to expose, no mortal remains to give a proper burial, just helpless reverberations.

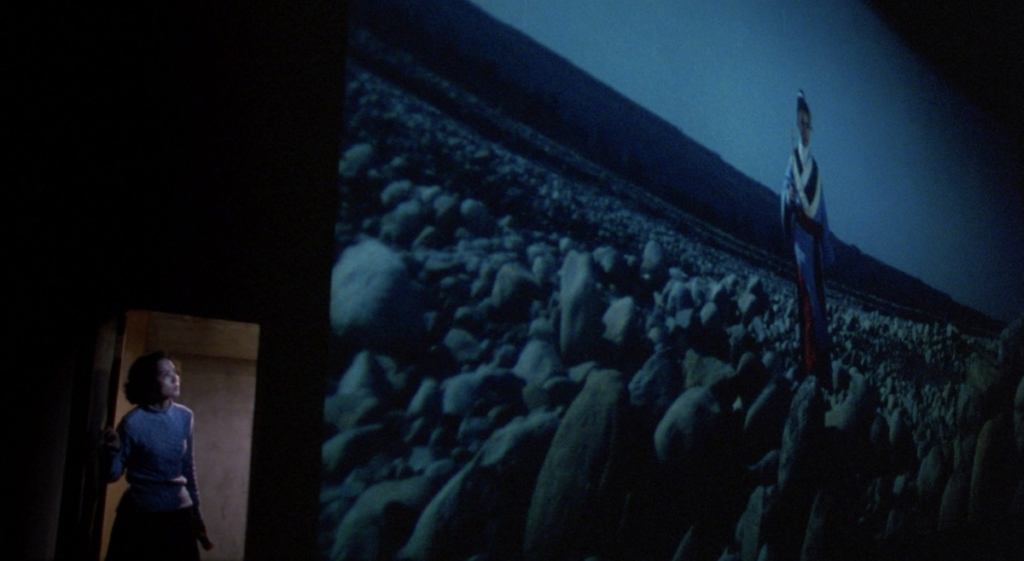

In John Carpenter’s 1987 film Prince of Darkness, quantum physics students investigate a glowing cylinder hidden at a Los Angeles monastery. They hail from Kneale University — not an homage that Nigel appreciated, though the influence of his futurist ghost stories would be obvious regardless. The mysterious relic turns out to contain Satan in liquid form; gnosticism by way of Tales from the Crypt. Like so much of Carpenter’s work, it’s a siege movie, but the invading force happens to be the cosmos. Rather than the old image of a torch sputtering out, this demon arrives like an electromagnetic pulse. One possessed student sits at a computer, typing unnaturally fast: You will not be saved by the Holy Ghost. You will not be saved by the god Plutonium. In fact, YOU WILL NOT BE SAVED! A recurring vision shows a specter emerging from the church; Carpenter shot the scene on video and then filmed it again through a TV set, so that the murky prophecy appears to be a copy of a copy of a copy, decaying backwards from doomsday. The director’s own voice announces: “You are receiving this broadcast as a dream.” A transmission dated tomorrow, intimately unfamiliar.

The spirit-media analogy still resonates for me, because both violate the linear model of time. They’re fragments that continue to move. Early photographers used double exposures and other tricks to create images of the absent beloved. With cinema, reanimation became possible. Promoting the Phonoscope, his film-projecting machine, the inventor Georges Demeny boasted he would reverse oblivion: “How many people would be happy if they could only see once again the features of someone now dead. The future will see the replacement of motionless photographs, frozen in their frames, with animated portraits that can be brought to life at the turn of a handle. We shall do more than analyze, we shall bring back to life.” Yet without their scent, their whims, aren’t we really bringing back an idea of that person somebody else had?

The time is out of joint: That Hamlet line returns over and over in Specters of Marx, where Jacques Derrida coined the word hauntology. The critic-theorist Mark Fisher later popularized his concept to explore the “lost futures” suggested by post-war social democracy, so irresistibly that people will talk about the “hauntological aura” of an old playground or some 1970s public-service announcement. The ideas from Derrida’s original lectures get broadened and narrowed at the same time. He was speaking after the Soviet Union evaporated, trying to explain why communism’s “messianic and emancipatory promise” persisted into the supposed triumph of liberal capitalism. If ontology is the study of being, how can it account for a non-existent presence?

Phantoms roam around us, luring even a skeptical eye: digital artifacts, blurred afterimages, all the unexplained vibrations and hammering noise of modernity. Notional events, unrealized possibilities. Marx invoked gothic metaphors to describe the uncanny world capitalism made: vampires, werewolves, the poltergeist-dance whereby a table becomes a commodity. He called communism the specter haunting Europe before it was even fully born, and the ruling classes have frantically tried to exorcise it ever since. To use one of Derrida’s beloved double negatives, communism is both defeated shade and looming threat, the fist clenching through cemetery earth. Like the maid at the cursed manor, everybody swears they recognize its face. “A specter is always a revenant,” the philosopher wrote. “One cannot control its comings and goings because it begins by coming back.”

To commune with the dead, you need a darkened room

T. C. Lethbridge believed his ghost-recordings were doomed to repeat themselves, but shadows take inspiration from the walls they move along. In Clive Barker’s short story “The Forbidden,” young academic Helen visits a public-housing complex to use its graffiti as raw material for her thesis, only to learn that those messages were offerings to a murderous spirit, the Candyman. His hand is a hook, his scent cloying sugar, his chest a swarming nest of bees. The Candyman invites Helen to play a very literal game of exquisite corpse, and join him in posterity. “The sweetness he offered,” Barker writes, “was life without living: was to be dead, but remembered everywhere; immortal in gossip and graffiti.”

“The Forbidden” takes its structure from traditional ghost stories, swirling with eerie ambiguities. The Candyman never emerges until its final pages, and Barker describes him in the rough strokes of a child’s nightmare, the references to his “seduction” all ironic. For Bernard Rose’s film adaptation, coming near the end of the slasher-movie vogue in 1992, such self-conscious restraint would not do. They started by changing the wardrobe. This Candyman wears a shearling coat, befitting his new origin. A gifted painter, the son of slaves, Daniel Robitaille was lynched for loving a white woman; say the title into a mirror five times to summon him. Tony Todd’s princely bearing in the role gave flyblown flesh to Barker’s sensual prose, a performance that suffuses everything around it. His voice flows over you like a death mask: “I am the writing on the wall, the whisper in the classroom.”

The obsession running through Candyman haunts its own cinematic language. As the camera focuses on Helen’s face, we hear Todd’s sepulchral tones inside her head. When she gets consigned to an asylum, blamed for Candyman’s handiwork, the psychologist confronts her with surveillance footage of her own nightmares. Peering at the research she collected, a startled Helen notices the killer’s aura shadowing one photograph — perhaps the first slide-projector jump scare. (“The camera introduces us to unconscious optics as does psychoanalysis to unconscious impulses,” Walter Benjamin once wrote.) The Candyman often appears at the edge of the frame, inescapably still, and matching his rhythm the film hypnotizes itself into a trance. Dried blood forms cryptic sigils. Doomed romance resurfaces as yearning fear. Whenever these lovers meet, the moment is untimely.

Another contradiction keeps prodding: If Daniel Robitaille was tortured by a white mob, why does his spirit select many victims from the underclass of Chicago’s Cabrini-Green complex, his “congregation”? Nia DaCosta’s 2021 Candyman reboot agonized over this question, trying to come up with a satisfying backstory. The original disturbs me more by implying that historical trauma can whorl outwards until it becomes ubiquitous, part of the landscape, like scratches on celluloid. In happier ghost stories, a specter peacefully disappears after leading the narrator to its killer. That fantasy never made sense to me. You can try to erase a haunting, but records of that experience will show up somewhere, as the Candyman’s painted liturgy does. The dead exist outside time; any justice for them must lie in the future.

In 2014, to mark the centenary of the First World War, the artist Chloe Dewe Mathews made a series called Shot at Dawn, photographing sites where soldiers were executed for desertion. One officer tried to console a condemned private with liquor; insensibly drunk, the teenager had to be tied to a post for the firing squad, “hooked on like dead meat in a butcher’s shop.” No trace of that event remains visible in Mathews’s photograph, only a sighing bush surrounded by bare, brittle trees; a place emptied of life. She tried to closely follow the time and date of each execution, so the images might echo, and her compositions seem to be waiting for an arrival, a return.

The Two Sights, a study of supernatural beliefs in the remote Scottish Hebrides, frames its rare human figures as silhouettes, or far in the distance. Instead the director Joshua Bonnetta focuses on texture: Sunlight scouring the shore, grime obscuring a bottled ship, the moon dangling over a rural church at the hour entre loup et chien. Disembodied voices narrate stories projected across the veil separating death from life: “There’s a foretelling, or a rehearsing, you could call it, of what’s going to take place,” one local says. Another describes the Hebrides as “a thin place,” where the passage between heaven and earth feels routine. In these islands it is not extraordinary to hear, almost subliminally, the funereal song of a beached whale. The 16mm film stock Bonnetta used doesn’t record sound, which had to be captured separately; an opening shot shows him setting up his microphone on a desolate hilltop. Hooded, shadowed, the director might be a Celtic druid gathering a chronicle in stones.

To film studios, the analog equipment Bonnetta used is a relic as unnerving as some sacrificial sickle. In a recent n+1 piece, Will Tavlin documented how Hollywood abolished celluloid film, using a favorite strategy: get some other sucker to shoulder the risks of filmmaking. Digital projectors ended up costing theaters far more to maintain than the analog variety, with an abbreviated lifespan (albeit no pesky unionized labor required). A film print slowly disintegrates every time somebody watches it, changing into something else, but they can also survive for centuries under gentle conditions. The Hollywood studios enjoying their ever-growing control over production and distribution seem curiously disinterested in preservation, another expense forced higher by Silicon Valley’s accelerationist capitalism. These days they prefer to speak of “content,” like the nutrients fed to captive rats. Thousands of films will land inside a pauper’s grave of dead hard drives and obsolete file formats, quietly anonymous, unseen.

To commune with the dead, you need a darkened room. In his essay “Leaving the Movie Theater,” Roland Barthes described the cinema as “a dim, anonymous, indifferent cube where that festival of affects known as a film will be presented.” To him, this was love: “We turn our face toward the currency of a gleaming vibration whose imperious jet brushes our skull, glancing off someone’s hair, someone’s face. As in the old hypnotic experiments, we are fascinated — without seeing it head-on — by this shining site, motionless and dancing.” Barthes contrasted that ceremony with television viewing, where “darkness is erased, anonymity repressed; space is familiar, articulated, tamed.” Earlier this year I rewatched Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye Dragon Inn, which takes place during the final screening at a dilapidated Taipei movie house; it came out in 2003, a year after the Hollywood studios began negotiating their digital technology. Sitting inside a fancier theater, I felt attuned to Tsai’s extremely long takes, his sparse cast’s unspoken longing.

With its neglected catacombs, its rivers of rainwater, the Fu-Ho cinema from Goodbye Dragon Inn brings to mind a ruined temple, and one character does receive an omen from its fortune-telling machine; but Tsai never frames the building with simple reverence. He dwells on the tactile experience of filmgoing: feet peeling away from floors, defiant snacking, those flashes of idle lust. (Barthes again: “It is because I am enclosed that I work and glow with all my desire.”) A Japanese tourist spends the movie cruising other spectators, to hilariously meagre response. Vintage wuxia epic Dragon Inn plays out in the background, its muted soundtrack a spectral monologue. Tsai shows a star of the film watching his younger self, weeping above a faint smile, as if all his friends just threw him a surprise wake. Here the insistence on linear time can finally be surrendered: He moves so gracefully, the ghost who is me.

Look through a projector’s lens and the present dissolves, bares its seams: a meeting between the cascading past and the anticipated future. Is this how it feels as the séance-table starts trembling beneath your fingers, when absence makes a spectacle of itself?