Up on hind legs, leash in mouth, the dog looks at me with its head tilted, clearly wanting a walk. But where could we go, me and this dog? I am a body in the world; the pup is a cartoon on my screen. I clicked the unsubscribe link in an email newsletter from Eventbrite and there it was, this needy apparition. Some retention team commissioned these imploring eyes. I feel neither moved by them nor charmed by the stunt.

Dogs have nothing to do with Eventbrite’s brand, but a sad dog is notoriously good at inducing guilt. This ploy is so basic, so transparent, it’s almost a spoof. Other companies with similar retention strategies veer more explicitly into parody. Consider this Groupon gag: When subscribers cancel, they land on a confirmation page with a button labelled “PUNISH DERRICK.” Derrick, it’s explained, is the poor “guy who thought you’d enjoy receiving Groupon’s daily email.” When you click the button, a video plays, of someone throwing coffee in his face. Text then scolds: “That was mean, I hope you’re happy.” Ultimately — of course — you’re invited to “make it up to Derrick” by re-subscribing.

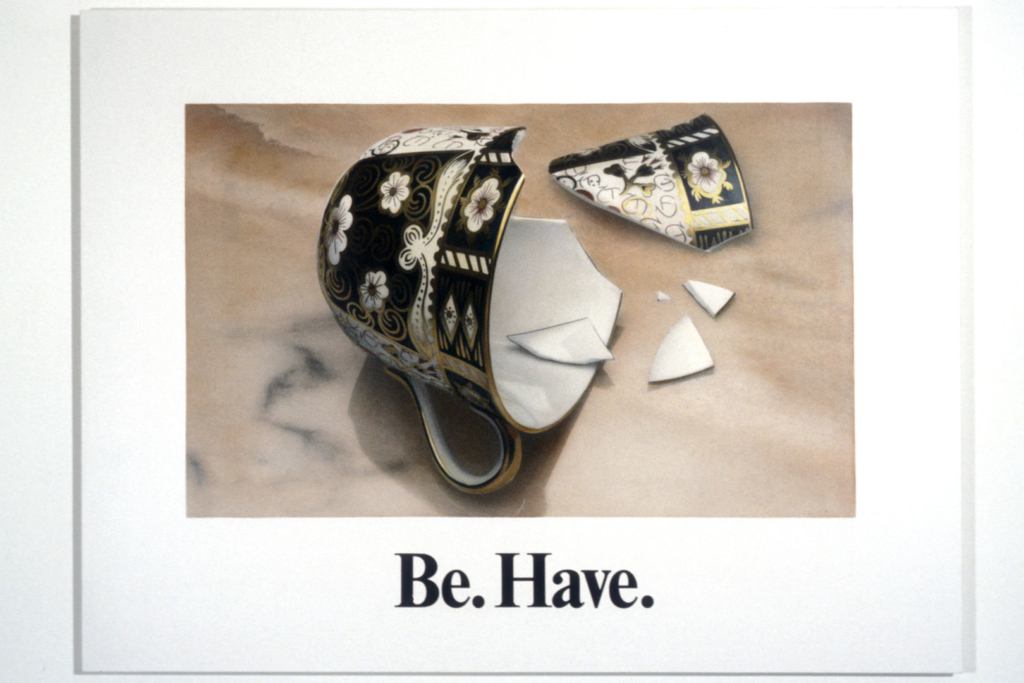

To sensationalize refusal is to normalize expectations of compliance

Whenever we opt out online, we risk light slander like this. It can happen when we cancel a subscription but also if we resist signing up in the first place. Ads that want our email addresses pop up and won’t go away unless we “admit” that we suck: “No thanks, I don’t want to look fabulous.” “No, I hate bargains.” No thank you, I’m a killjoy. The falseness — and the absurdity — of these extorted confessions vary. What’s consistent across these opt-in pop-ups (and the guilt-trip opt-outs) is the message that our refusals are invalid.

Such encounters help condition us: They remind us that we can’t count on opting out of anything unscathed. If we turn down an opportunity to “stay connected” with some advertiser, they may retaliate, trying to shame us for not going along with their agenda. They may chastise us for deigning to put our needs above their bottom line. They may cast us (if playfully) as mean and heartless, or dumb and wrong.

Perhaps this negging is the marketer’s stab at the comedian’s “punching up.” The “joke” smuggles in the premise that consumer choice is a kind of sovereign power, and positions brands as the scrappy underdogs speaking truth to it. But consumers don’t actually have that much power. Though we’re framed as tyrants, we can’t really punish Derrick, or deny a dog a walk. Eventbrite didn’t even let me cancel when I wanted to: I had to make numerous weekly unsubscribe attempts before I finally stopped receiving its promotions.

The contemporary customer isn’t so much always right as always inundated. This overwhelm is a given of the internet age, and we’re expected to accept it graciously. The whimsy of certain unsubscribe messages is a misdirection by which brands obscure the actual reasons, prudent or trivial, we want out. Unwanted emails waste energy and clutter our private space. It’s enough, though, for us to say that they’re unwanted; our attention should be ours to spend as we will. When brands make a spectacle of our rejection, they undermine this agency and mock the respectability of even a quotidian “no.” Ultimately, to sensationalize refusal is to normalize expectations of compliance.

Customers are not literally oppressed, but the bolder unsubscribe messages I’ve encountered do borrow oppressors’ tactics. They entrench and exploit norms of compliance, undermining agency and policing tones. They disavow their own power and perform fragility. When companies question your judgment for cancelling their correspondence, they repeat the flawed arguments (debunked, for instance, here and here) leveled against “cancel culture” — that the status quo is working for everyone; that complaints against it are gratuitously punitive; that accusers have the power to destroy. With an email newsletter, the stakes may not be huge, but the structure is insidious.

To leverage its “hurt” feelings, a company must pose as a sentient, personified presence. Rare is the unsubscribe response that doesn’t claim to feel something about your leaving: even the most respectful companies are “sad to see you go,” or “sad to see you go!” or “sorry” to see the same. Many want you to know that “you will be missed,” insisting in the first person that they’ll “miss you” or “really really miss you.” Before you can close the tab, some blurt that they “already miss how close we used to be.” (I encountered all these and more in a recent unsubscribing flurry.)

Sometimes, brands even frame the connection they have with us as romantic. When Uber’s reputation floundered in 2016, Lyft attempted to sweep in with the promise that it was “the better boyfriend.” And menswear brand Bonobos explicitly equates unsubscribes with breakups: To confirm your intention to stop its emails, you can choose to “take it slow” to reduce the frequency of their newsletter; you can pause the subscription by announcing “it’s not you, it’s me;” or you can unsubscribe for good with “*sniff* It’s over, Bonobos.” Taking this trope to its logical conclusion, software company Hubspot presents unsubscribers with a video featuring their director of inbound marketing in a caricature of the clueless, pathetic boyfriend who can’t accept rejection.

Some marketers don’t even promise you anything for staying. It’s just that if we leave, we’ll hurt their fake feelings

Watching that video helped me understand my fury at the others. All those irksome messages were — to greater and lesser extents, and more and less self-consciously — evoking the bristling, sulky archetype of the jilted narcissist ex. Perhaps most confounding of all is that Groupon, Eventbrite, and others don’t even promise you anything for staying. It’s just that if we leave, we’ll hurt their fake feelings. How is this incentive? They could sell themselves, but instead these companies leverage dangerous, pervasive cultural attitudes about rejection. Their messaging implies that rejection is so catastrophic, and resilience so scant, that we’re obliged to protect others’ feelings at our own emotional expense. That’s a manipulative racket, whether it involves humans or brands.

Kristen Roupenian thematized this norm in her viral 2017 short story “Cat Person.” The story follows Margot and Robert as their relationship proceeds from from casual flirting to drunken hookup. Margot wants to stop but finds it nearly impossible to extricate herself: “the thought of what it would take to stop what she had set in motion was overwhelming; it would require an amount of tact and gentleness that she felt was impossible to summon.” Margot fears that “insisting that they stop now, after everything she’d done to push this forward, would make her seem spoiled and capricious, as if she’d ordered something at a restaurant and then, once the food arrived, had changed her mind and sent it back.”

Treating commercial transactions and intimate negotiations interchangeably, the character assassination Margot imagines has the tone of an obnoxious ad stunt. Still in bed with Robert, Margot humors him until she can “escape” and doesn’t contact him afterward. Oblivious, he reinitiates conversation, eventually texting with a line I could see receiving from a brand I’d rejected: “I know I shouldn’t say this but I really miss you.” When she doesn’t answer, Robert sends a stilted monologue of texts that imagine Margot’s motivations for dumping him. The one-sided correspondence devolves into slut-shaming sneers, and the story ends there.

Here on my screen, text beside the sad dog now asks, nonsensically, whether we can “still be friends.” Bypassing the bright, central button that would pause rather than cancel my subscription, I find the homely, uncolored one under “No thanks.” Pressing it causes the dog to slump in defeat. Or is that contrition? Eventbrite has a poll prepared that guesses at my reasons for quitting. “Too many emails” is the first option, which isn’t wrong.

“Maybe I was too old for u or maybe you liked someone else” guesses Robert in Roupenian’s story. The reasons for leaving on my screen include: “These events aren’t in my area” and “Not interested in recommendations.” Good guesses, and their presentation suggests some commercial equivalent of empathy. But the option that best reflects my situation is last on the list. It describes my experience not only with this transaction but with the whole complex of values and norms that produced it: “I never signed up for this.”