In 1980, Atari hosted a national Space Invaders championship in New York. One of the only images from the event shows four finalists, including the eventual winner Rebecca Heineman, staring upwards at four separate television sets. Compared to the high-gloss, blockbuster theatrics of modern eSports, the grainy photo feels quaint, typified by the cute game mascots positioned prominently on top of the cathode-ray tube TVs. But perhaps the most noticeable difference is what the four competitors are sitting on: a set of beautiful if impractical Cesca chairs designed by prominent Bauhaus member and modernist Marcel Breuer, a far cry from the conspicuously ergonomic furniture of today. The foursome appear to be both slumping into their shoulders and craning their necks, two seemingly contradictory actions, while their eyes track the hordes of hostile aliens.

Today, eSport athletes sit in racing-car-like seats, their spines supported by high backrests, padded lumbar regions, and adjustable cushions. In the rafts of video game broadcasts and livestreams on sites such as Twitch and YouTube, an army of content creators appear as nothing more than floating heads, framed not only by whatever video game they’re playing, but the gaming chair behind them, its distinctive form creeping up past the back of their necks. The chair is a relatively recent invention: DXRacer, originally a carseat manufacturer, claims to have created the first one in 2006. Today, most chairs carry a little of that motorsport DNA through their streamlined shapes and garish decorations. These seats advertise greater comfort to users likely to spend hours in front of a computer; they also convey seriousness in a new and contested discipline, and a sense of motion for a sport rooted in inertia. They’re an interface between the action onscreen and the largely motionless body behind the controls.

Cougar Ranger gaming sofa

DXRacer’s design was quickly replicated by other manufacturers, finding widespread use. Today, some models double as office chairs, appealing to a potential consumer base of sedentary workers concerned with the musculoskeletal issues involved with desk work. But many would seem ridiculous in any realm other than gaming. The bestselling gaming chairs on Amazon are contoured like HR Giger designs, and look as if they could shoot lasers from their armrests. Many feature massage settings, bluetooth speakers and subwoofers in addition to the standard lumbar support. The comfy-looking Cougar Ranger gaming sofa is a souped-up recliner designed for long gaming sessions; it would look more at home in an amusement park than it does in the average living room.

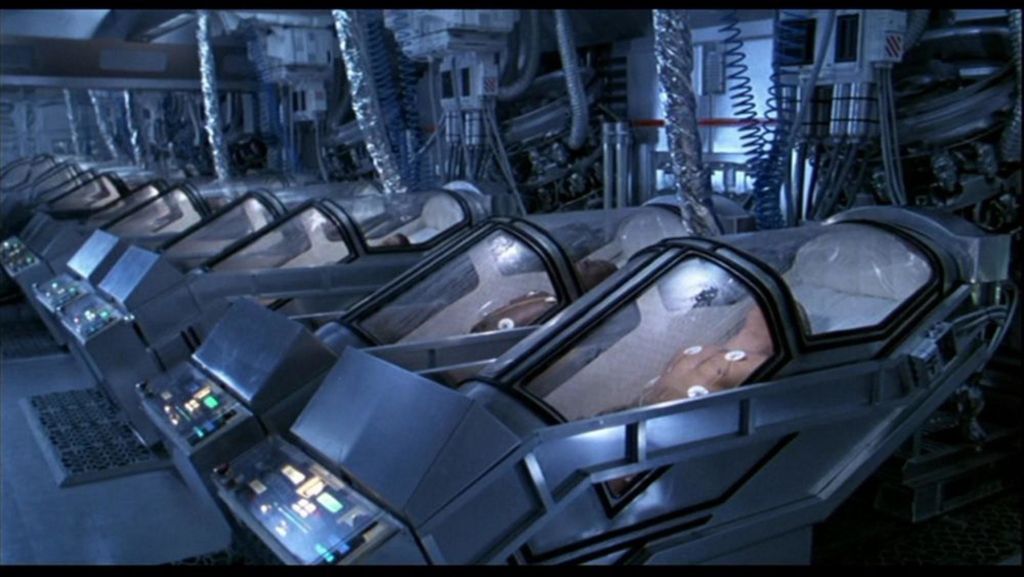

Some of these contraptions are less chairs than they are living spaces: sites for work, play, rest, and activity that the user barely ever has to leave. Two years after DXRacer’s first design, the monstrous $100,000 Ovei Pod debuted: a climate-controlled, leather-upholstered capsule with 5.1 surround sound and optional surround viewing reminiscent of the Hypersleep Chambers from 1979’s Alien. In March of this year, as lockdowns were introduced across the world, Japanese company Bauhutte — inventor of the “gaming camp,” a tent-like enclosure for one’s desk — revealed its gaming bed, a set of furniture and accessories which surrounds the user as in a hospital room, complete with “Energy Wagon” for snacks and beverages. One video game journalist jokingly referred to it as “gaming’s final form.” Here, LED lights replace the sun, moon, and stars; circadian rhythms are supplanted by the ebbs and flow of software use.

Perhaps the most bizarre of these extreme gaming chairs are the cartoonish “zero-gravity” workstations which appear to suspend users in mid-air. (Even relatively familiar-looking chairs like the gaming sofa boast extreme reclines.) The elaborate Predator Thronos, a gaming shell made to look like the cockpit of a warplane, promises to “warp your reality” with the “cocoon-like” immersion of its cabin, the bass-driven “deep impact haptics” of its seating, and the “vision-filling embrace” of its triple display setup. Its design reflects the ominousness of its name: “Thronos defines itself with cold, black metal shaped into a hardened exterior. Iconic cut-outs along the entire body reveal a chilly RGB glow, lighting up the darkened shell of the machine.”

Bauhutte’s Gaming Bed setup

The implication of such designs — that the pressures of gaming on the body dissipate in the right conditions — is reflected in the marketing copy for the recently unveiled “scorpion cockpit.” The object, an arachnid-induced techno-nightmare, promises to eliminate fatigue from the user’s neck and back with a modular scorpion-tail backrest, thus enabling “longer immersive experiences.” This chair speaks to seemingly conflicting impulses: on the one hand, the zero-g element, a nerdish fantasy in itself, is reminiscent of amniotic fluid, cradling the embryonic user; on the other, its militaristic design feels sinister (and not just because of the game industry’s troubling relationship with armed forces). It looks more like a battle station — a weapon against reality, a harbinger of death.

As these designs have gotten more absurd, they’ve become increasingly acute manifestations of the 40-year push by technology companies to close the gap between people and their devices. The majority of this attention has been focused on input devices: mice sit in downturned palms, ready to glide across the desk; the keyboard contains a dizzying array of configurations designed to minimize the time between intent and execution; and the modern video game controller, featuring two rotatable sticks, enables players greater facility and finer motor control within virtual spaces. Esports enthusiasts fetishize a range of electronics (including high-end monitors and wireless headsets) which supposedly facilitate quicker reaction times and smarter decision-making. But what you sit in is as much a part of engaging with such technology, capable of transforming mood and atmosphere, causing either comfort or pain. DXRacer’s marketing spiel — “Sit better. Work harder. Game longer” — recalls other workaday products that promise to “optimize” their users’ lives, but with emphasis on a particular characteristic: endurance.

DXRacer’s Ovei Pod

Modern video games tend to demand endurance of their players. Open worlds of the kind Grand Theft Auto popularized are now so vast, filled with so much detail, and feature such complex interlinking systems that they are almost inexhaustible as a source of entertainment. These worlds used to resemble elaborate virtual movie sets, locations in which single players participated in scripted stories, but online components have altered their functionality. Now, hundreds of players exist in these networked spaces simultaneously. As for eSports, online titles such as Fortnite and Counter Strike lack the physical constraints of their traditional counterparts. Servers don’t operate according to opening and closing times, games are officiated by code, not humans, and so the possibility of one more match teases the player even as their concentration and enthusiasm wanes. Overwatch, a competitive shooter with a cast of extraordinary characters, enables players to overcome their own corporeal limitations and pull off what appear to be superhuman feats onscreen even as they remain static in their gaming chairs.

As players sink more hours into the game, learn to read audio-visual cues, adapt to its control scheme, and quicken reaction speeds, their proficiency naturally improves. Throughout this process, players access cognitive states of “flow,” moments of extreme focus in which they become mentally and physically synchronized with the game. This is often described in transcendent terms: the player’s peripheral space dissolves, time contracts, and they willingly enter into what feels like symbiosis with the machine. This isn’t always constructive. In 2012, 23-year-old Chen Rong-yu died in a Taipei internet cafe after playing League of Legends, a popular MOBA (multiplayer online battle arena), for more than 20 hours. Chilling pictures show the final shape his body occupied, arms and hands stretched out towards a keyboard and mouse as a result of rigor mortis. A year earlier, 20-year-old Chris Staniforth died following an all-night session playing first person-shooter Halo Reach online. An autopsy revealed the cause of death was a pulmonary embolism as a result of deep vein thrombosis, a blood clot which formed in his legs. The condition is most commonly associated with people who are largely immobile.

Cluvens’ Scorpion Cockpit

While the gaming chair is marketed as a medical boon, it essentially renders large parts of the body motionless except, of course, those limbs interfacing directly with the computer. These chairs emphasize their ergonomic benefits (“extreme comfort for healthy gaming” reads the DXRacer FAQ) and a new level of work-life optimization, but encourage harmful behavior — either in the short term, as in extreme gaming sessions, or the long run, as muscles gradually atrophy. This strange image devised by Canadian gambling site Online Casino offers a glimpse into the possible consequences of gaming addiction: It depicts Michael, “a visual representation of the future gamer,” who is riddled with a cornucopia of afflictions, including a hunched back, indented skull, and a variety of joints swollen by repetitive strain injury. Supposedly a warning to customers against the pitfalls of marathon gaming sessions, it appears to be more spectacular than that — Michael is a nightmare, but he’s also a morbid fantasy.

Hypersleep Chamber, Alien (1979)

There’s an element of surrender in the way users give up their bodies to games, which is literalized in the design of chairs that cocoon and immobilize them — chairs that aim, as much as possible, to minimize any reminder of the player’s embodiment. Perhaps what gaming chairs resemble most, in their myriad and often grotesque forms, are props from David Cronenberg movies. In 1983’s Videodrome, a VHS tape causes tumors in the watcher that gradually take over their brain. 1999’s eXistenZ features peripherals which literally slide into the player’s flesh, facilitating a video game described as “the most effective deforming of reality.” By the end of Videodrome, Max Renn (James Woods) is so colonized by technology that he lacks the capacity to think for himself. “Long live the new flesh,” he says, before killing himself.

In these films, the relationship of human to machine is one of prey to predator. The naming and shape of the “scorpion cockpit” resonates here, as there is something particularly insect-like about the interaction between human host and device: consider the tarantula hawk, so-called because it paralyzes the spider with its sting and leaves it as living feed for its larvae; or the lancet liver fluke, which “zombifies” ants, compelling them to offer themselves up to mammal predators, in whose guts the worms reproduce. “Insects don’t have politics. They’re very brutal,” says Seth Brundle, the metamorphosing protagonist of The Fly. “No compassion, no compromise. We can’t trust the insect.”

Despite the eventual demise of his characters, Cronenberg frames the transformative potential of technology as psychosexual: new orifices are created and penetrated by hardware which subsequently overtake the body. The gaming chair is similarly predatory, but its effect is more of a slow paralysis — eroding bodily functions until all that remains are those which merge with the computer, a process defined by bodily decay rather than carnal awakening. In either case, the host enters willingly into a dynamic whose ultimate outcome is death.