Topics

Parasociality

Friends you don’t know

Feel for You

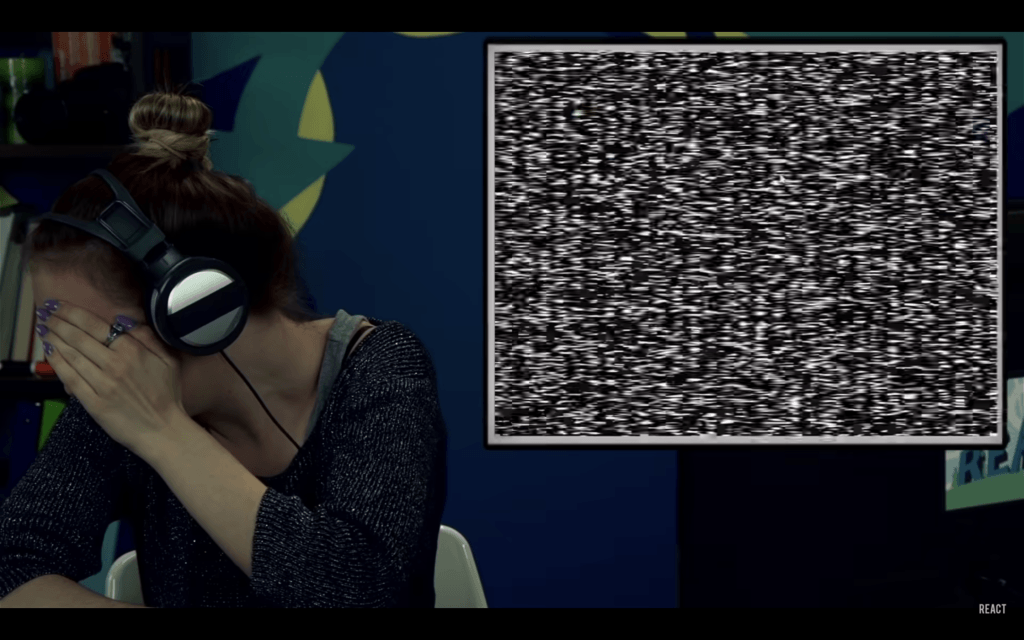

Reaction videos are pleasantly numbing — they ease the constant pressure to “react” to people and events online. This sort of content arrives to us pre-metabolized: all we have to do is absorb it

The Great Beyond

The social media profiles of the dead persist after they are gone. They have become pilgrimage sites for mourners who come to them and post messages addressed directly to the deceased, in second person, as if they were a portal to them. This amounts to a mainstreaming of a form of public mourning that had been marginalized to seances and encounters with psychics, in which speaking to the dead is seen as an ongoing open conversation.

Take Me Away

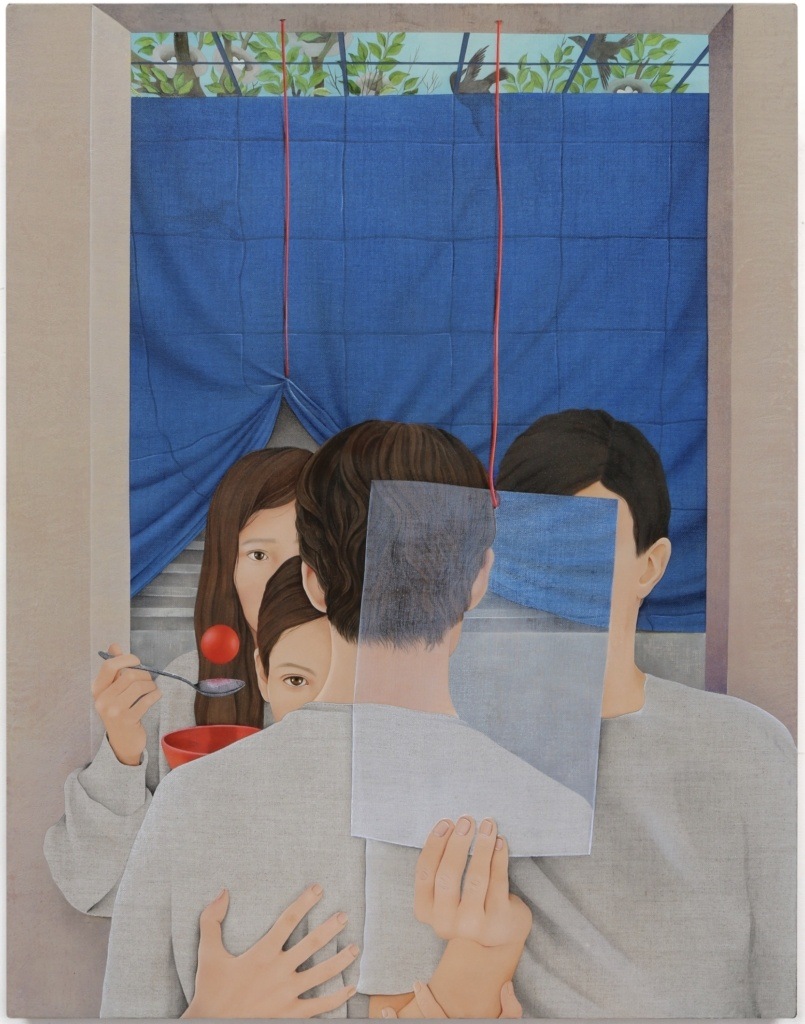

Compared to earlier technologies of escape, parasociality offers something closer to direct interaction — a more powerful illusion of connection. Parasocial escapism is not so much a retreat from intimacy into consumerism, but a way of consuming intimacy as a product

Trust Me, You Want This

Host-read ads on podcasts — when the hosts ad-lib and joke around with the copy provided by sponsors — are a kind of “parasocial” advertising, in that they use the sense of intimacy and pseudo-friendship podcasts produce to overcome the listener’s defense mechanisms against marketing. Joking around with the ads makes those ads integral to the sense of community that listeners derive from podcasts and the sense of belonging they generate.

Why Can’t We Be Friends

Friendship is not an unchanging concept; changing economic conditions and technological possibilities facilitate different demands for connection and structures of belonging. “Parasociality” — feeling an unreciprocated intimacy with media personalities — is one such structure of belonging, but its asymmetry always tilts into economic exploitation or explosive fan rage. The same media forms that nurture that rage are also capable of amalgamating it into a potent force of social disruption.