SYLLABUS FOR THE INTERNET is a series about single books or bodies of work written prior to the rise of the consumer internet that now provide a way to understand the web as we know it today. View the others here.

In life, the German writer W. G. Sebald was known as a luddite, working on a typewriter and eschewing computers and the internet. He died in December of 2001, of a heart attack at the age of 57, and thus never lived to see the rise of social media. And yet, his work remains remarkably prescient for understanding this world we now inhabit, a world where historical trauma is under near-constant threat of erasure by state actors, and where nominally straightforward documentation of everything from street protests to the Covid-19 pandemic is constantly disputed, discredited, or manipulated on behalf of ideological and partisan interests.

While nominally a fiction writer, his four major prose titles — Vertigo (1990), The Emigrants (1992), The Rings of Saturn (1995), and Austerlitz (2001) — seem to defy categorization. These works, each published in the last year of his life, followed a solid but undistinguished career as an academic, teaching literature mainly in England, and they seemed to emerge from nowhere, with their pages-long sentences, unending paragraphs, and a tone so shot through with melancholy it seems unworldly, as though dictated by someone in a fugue state. This tone puts them at odds with — and makes them germane to — the kind of reading that most of us mainly do in the 21st century.

Long before anyone’s routine consisted of sifting through algorithmically delivered chunks of news and images, Sebald recognized the suspicious anxiety inherent in such consumption

Born in 1944, Sebald grew up in a small German town, coming of age in a time of perilous silence where adults refused to talk about the war or their involvement (including his father, who served as an officer under the Nazis during the war). This silence would impact his work, which revolved around themes of historical erasure and forgetting, particularly regarding the Holocaust and the Allied firebombings of German civilians. Despite Sebald’s obsession with the distant past and an almost timeless quality to his work, reading these books — wherein the reader is confronted with a history that seems, at first, straightforward, but is revealed to be a shifting morass of sources, many of which contradict each other — turns out to uncannily reflect the way most of us now find ourselves trying to make sense of information on the internet.

His work remains theoretically prescient: Long before anyone’s daily routine consisted of sifting through algorithmically delivered chunks of news and images, Sebald had recognized the suspicious anxiety inherent in such consumption. Rather than try to overcome the problem, his works embrace it, modeling a kind of active reading of the history that embraces the treachery of the past rather than repressing it, accepting the unreliability of all individual sources, but also the obligation to make sense of them.

By the time of his death, Sebald had already been catapulted to international literary fame: For Susan Sontag, he was the answer to the question, “is literary greatness still possible?” In the last year of his life, he was shortlisted for the Nobel Prize in literature. Since then, his influence has grown, with writers from Teju Cole to Lily Tuck explicitly acknowledging their debt to his work. It’s difficult, if not impossible, to imagine the recent rise of autofiction, by writers like Rachel Cusk and Ben Lerner, without his influence.

Beyond the literary world, the publication of Carole Angier’s Speak, Silence: Searching for W. G. Sebald — the first major biography on the writer — has brought a resurgence in interest, and a new interrogation of his working methods. As Dwight Garner wrote in his Times review, Angier’s book “can’t have been easy to write.” Angier was restricted in her ability to quote from Sebald’s work, and forbidden to quote from numerous private sources; Sebald’s widow refused to participate. Moreover, as Garner writes, “Sebald was a serial dissembler about nearly every aspect of his life and work… he stole ruthlessly, from Kafka, Wittgenstein and countless others, to the extent that some of his books are nearly collages.” This creates, in many instances, a sense of moral ambiguity, but it also encapsulates his project, which starts from the assumption that memory and historical documentation is inherently unreliable.

Dislocation, after all, is a recurrent theme in his books, often figured through travel and displacement. In Vertigo, a very Sebald-like narrator retraces the real-life journeys of Henri Marie Beyle (better known by his pen name, Stendhal) and Kafka; The Emigrants tells the stories of four different Germans forced to leave their home country; The Rings of Saturn is composed of the narrator’s meandering walk through East Anglia in England, triggering a series of engagements with the past, traumatic memories, and erased histories. Austerlitz, his final book and the one that reads most clearly as a novel, tells the story of Jacques Austerlitz, shipped off to Wales from Czechoslovakia on the kindertransport, who sets out late in life to rediscover his identity and search for traces of his parents, both killed in the camps.

A post-war silence would impact his work, which revolved around themes of historical erasure and forgetting

In each text, in differing forms, one or more figures attempt to reconstruct or unearth a past buried under trauma and forgetting, attempts that are never fully successful. Sebald is known in the United States as a Holocaust writer — the Holocaust is a major theme of both The Emigrants (three of the four central figures have Jewish ancestry, and their departures from Germany are all related, directly or indirectly, to the Holocaust), and Austerlitz — but his concerns were broader. The Holocaust was one of many symptoms of a larger breakdown of modernity itself, a catastrophe that we still labor under. Sebald understood that many of the same Enlightenment ideas that ushered in progressive values and humanist philosophy also paved the way for the atrocities of the 20th century, many of which were exemplified by calculations for maximizing the deaths of civilians in war and the logical precision of genocide. Behind his associative and seemingly stream-of-consciousness style lies an attempt to unearth the fragile threads that connect European culture and philosophy with its darkest manifestations.

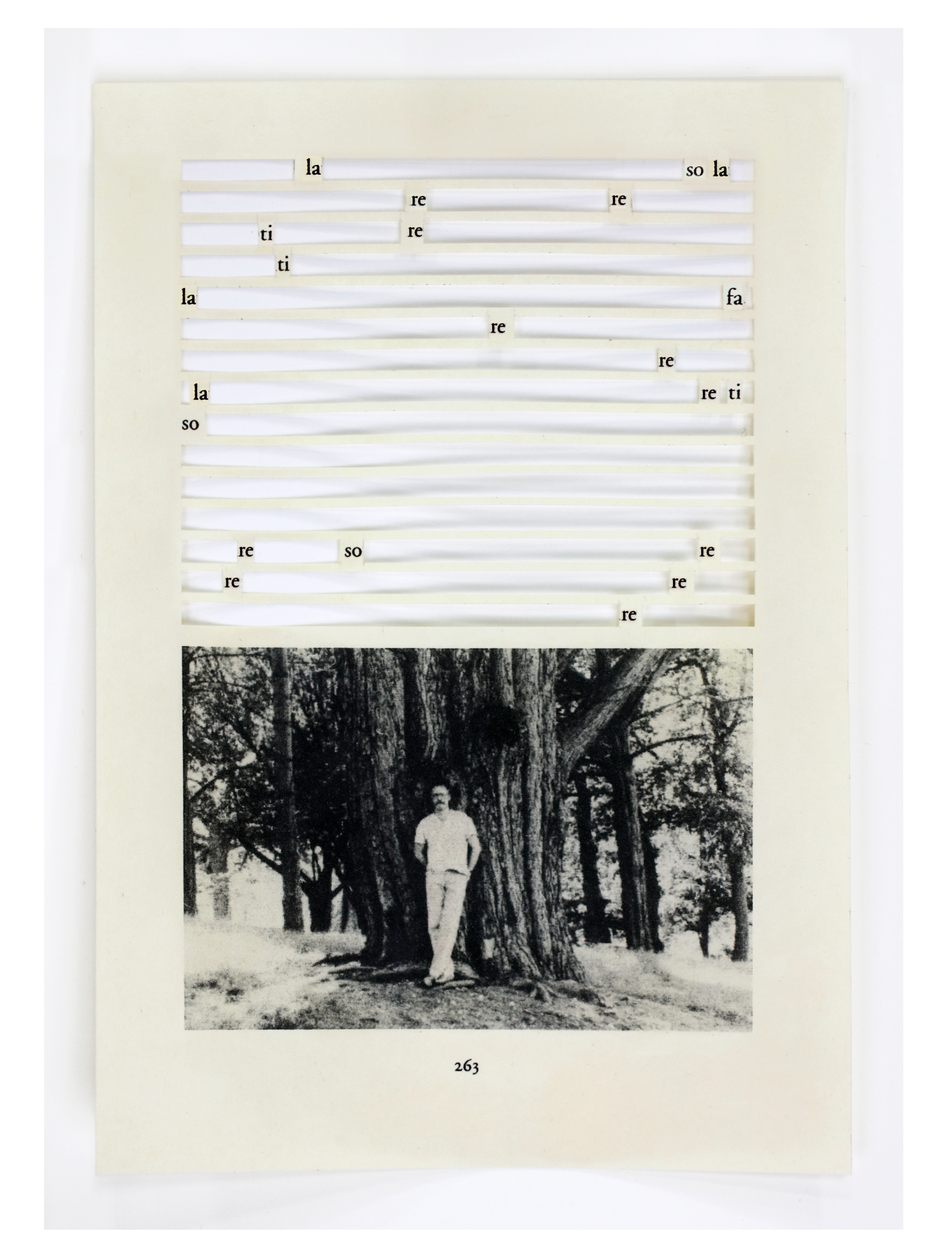

These books read at times like travelogue and memoir, though there were obviously fictionalized elements; they were full of historical sources and citations, but lacked footnotes or any other scholarly apparatus; and, most distinctively, they embedded photographs and other images directly into the text. The embedded images do not appear separate from the text, as plates with captions, and are rarely remarked upon formally, appearing instead as kind of ghostly interruptions or a parallel commentary on the proceedings.

It is tempting to treat the images in Sebald’s books as illustrations. Again and again, a description in the text is accompanied by a photograph that seems to show what’s being described: in The Emigrants, for instance, Uncle Kasimir describes his work as a laborer installing copper sheeting on the Chrysler Building, accompanied by a photo of the skyscraper’s Art Deco summit. Such images seem to say, “‘It’s true, what I’ve been telling you’ — which is hardly what a reader of fiction normally demands,” Susan Sontag wrote, of Vertigo. “To offer evidence at all is to endow what has been described with words with a mysterious surplus of pathos. The photographs and other relics reproduced on the page become an exquisite index of the pastness of the past.”

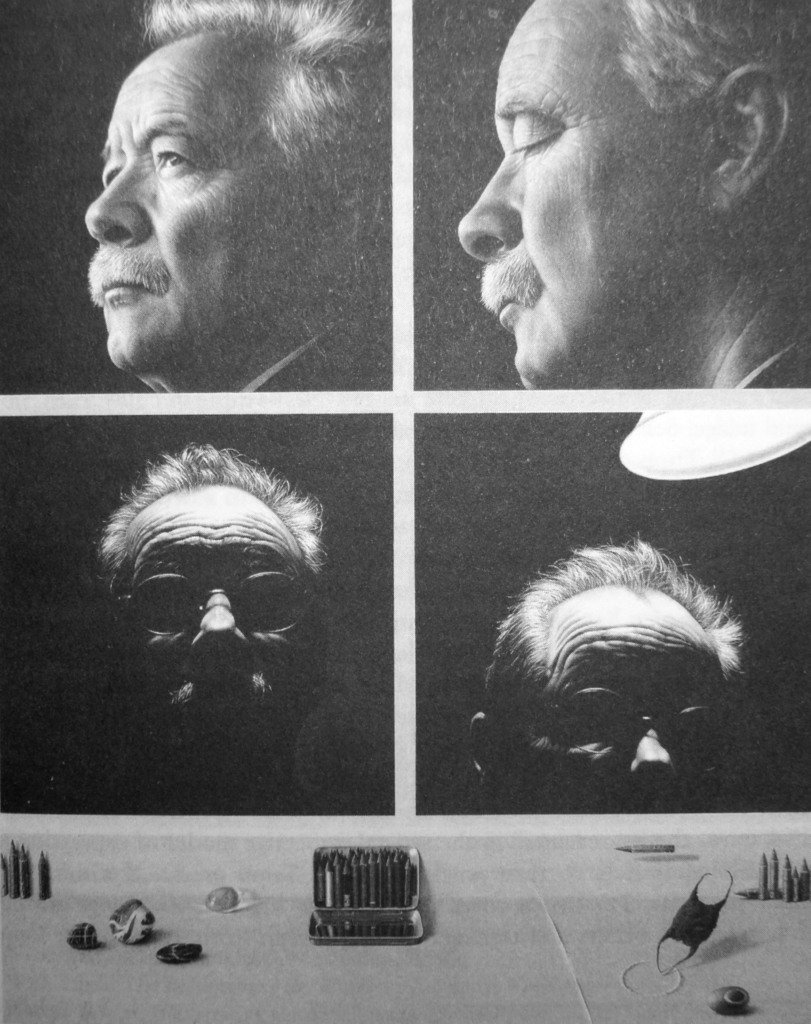

Image: L’Oeil oder die weiße Zeit (The Eye or the White Time) (2003) by Sebald collaborator Jan Peter Tripp.

But what these images actually index is deceptive. Throughout Sebald’s work is a constant reminder that images cannot be trusted, and that they regularly conflict with memory and history. The opening of Sebald’s Vertigo relates a story from Stendhal/Henri Marie Beyle’s time in Napoleon’s army as they crossed from Switzerland into Italy, reaching the town of Ivrea at sunset. In his memoir, Beyle wrote that for years he remembered this scene in great detail; but after seeing an engraving he thought “a very good likeness,” the engraving overtook his own recollections. He concludes, “my memory now is nothing more than the engraving.”

Sebald retells this journey, incorporating Beyle’s own sketches of the events, which he’d included in his memoir. “Beyle’s advice is not to purchase engravings of fine views and landscapes seen on one’s travels,” Sebald remarks, “since before very long they will displace our memories completely, indeed one might say they destroy them.”

This passage not only reflects Sebald’s working methods — extensive paraphrasing, building up his own narrative through a collaging of other sources — it is also key to understanding the way Sebald uses images. Photographs, paintings, and other documents, Sebald warns, often serve to supplant, not enhance, the narratives they mirror. Rather than verify or authenticate a memory, they instead call into question the very notion of an “authentic” memory.

Photographs are no less deceptive than engravings or paintings. In a 1997 essay on Franz Kafka, Sebald writes that the “whole technique of photographic copying ultimately depends on the principle of making a perfect duplicate of the original, or potentially infinite copying.” And because such copies outlast their referents, Sebald goes on, they’ve often triggered “an uneasy suspicion that the original, whether it was a human or a natural scene, was less authentic than the copy, that the copy was eroding the original, in the same way as a man meeting his doppelgänger is said to feel his real self destroyed.”

For a writer obsessed with the question of how one might recover the past, Sebald takes pains — again and again — to remind his reader that not only is memory unreliable, but so are the technologies that supposedly aid it. In 2022, this question pervades daily life. Sebald’s most noteworthy contribution to this problem was to build a literary form that dramatizes this problem, while simultaneously offering a series of possible ways forward.

It is a strategy that has its pitfalls. Carole Angier’s book alternates between straightforward Sebald biography, readings of his major works, and an attempt to unearth the historical and biographical subjects he used as models. Repeatedly, she finds that Sebald distorted his original source material, often to the dismay of those involved, or outright invented elements that he would later insist in interviews were true. She reports that many of the people she tracked down were “furious” at being used as models; the English artist Frank Auerbach, on whom Sebald based “Max Aurach” in The Emigrants, threatened (according to some accounts) to sue Sebald’s German publisher. In the English edition, the character’s name was changed to “Max Ferber” and all other overt references to him were removed.

Angier often reports this as betrayal, and reads his oeuvre as one of subtle duplicity. She recognizes that much of what Sebald is doing is within the realm of art: collaging and adapting other writers and sources who are either dead or made unrecognizable within the writer’s larger project. She surmises that, as a person and as a writer, Sebald was “drawn to trickery,” and this may explain why he seemed to be comfortable with blurring the line between truth and fiction. But she is troubled by two interpolations in particular. One is Susi Bechhofer, who wrote a memoir of her experiences on the kindertransport that Sebald borrowed heavily from. Upon reading Austerlitz, Bechhofer had intended to ask Sebald to be credited, but he died before she could do so; her lawyer’s request to his publisher along similar lines went unanswered.

Second is the character of Luisa Lanzberg in The Emigrants. A friend, Peter Jordan, provided much of the details that made up the character’s backstory; he told Sebald about his mother, Paula, and loaned him an unpublished memoir by his aunt, Thea Gebhardt, detailing life from before the war. Sebald condensed Gebhardt’s 80-page memoir into a 25-page passage attributed to Lanzberg, using her vivid descriptions and memories to conjure up pre-war Germany. A photograph of Gebhardt appears in the novel, and without any attribution or caption, one might reasonably assume it’s the fictional Lanzberg.

Angier finds both of these appropriations troubling, and calls for some kind of formal recognition in The Emigrants and Austerlitz of these two sources. As she explains, “If we are reminded that Luisa is not real, but Paula [Jordan’s mother] and Thea were, we start thinking about Paula and Thea instead. That is what I want to achieve here.”

Though it’s tempting to treat the images in Sebald’s books as illustrations, what these images actually index is no less deceptive than engravings or paintings

It can be a deeply unsettling thing to find yourself or your loved ones written about by someone else without your knowledge or permission, particularly if the facts seemed changed or distorted. It conjures a feeling of helplessness. Giving space to such voices, it is easy to see the humanizing impulse in Speak, Silence, which is an important work of restitution. The biography raises difficult questions that don’t have easy answers, and which will lead some, ultimately, to conclude that Sebald’s project is fatally ethically compromised.

While Angier wants us to think of Paula and Thea, Sebald, she acknowledges, didn’t. “He wanted us to believe in Luisa Lanzberg. He wanted us to believe in her so much that he put her photograph in the story. But now we are back to that dilemma — the photograph itself makes us wonder who was behind Luisa Lanzberg.”

But I’m not sure it does. To read a writer whose oeuvre contains constant reminders that photography is unreliable, and then wonder about the “real person” behind a given image, seems to risk missing the artistic project entirely. Angier’s project leads her to insist that there is a truth beneath the fiction — one that can be known and documented — in a way that I find troubling. In 2022 we can no longer take for granted that a photograph is an index of its subject, that the photograph in The Emigrants is dispositive of Thea Gebhardt in a way that’s more fundamental than it is of Luisa Lanzberg. A photograph, after all, can only tell us so much — it cannot say who took it, or why, or under what circumstances, or in what context. It cannot say what may have been staged or altered in order to create the shot. It cannot say what may lie just outside the frame. Ultimately, Sebald’s project is not about fidelity to the historical record, and so Angier’s critiques — however valid in their own right — seem to ignore the purpose of the work.

The naïve belief that historical documentation could be sufficient for establishing a collective sense of truth — stemming the tide of disinformation, partisanship, and malevolence — has been disproven again and again, particularly over the past five years. Photography — far from a means of establishing historical truths, and thus preventing their repetition — is infinitely manipulable, a tool in the hands of surveillance states and increasingly sophisticated visual propaganda. (Trump’s time in office began with digitally cropped photographs to distort the size of the crowd attending his inauguration.)

Sebald himself was well aware of this, even before our current age of digital manipulation, and had a longstanding distrust of documentation and archival material. Critic Mark Anderson notes how “Sebald took specific exception to films like Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, whose faux-documentary style — the grainy black-and-white photography, the hand-held camera — lures viewers into thinking they are watching the Holocaust unfold before their very eyes.” In a 2001 interview with Arthur Lubow, Sebald noted that the “process of making a photographic image, which purports to be the real thing and isn’t anything like, has transformed our self-perception, our perception of each other, our notion of what is beautiful, our notion of what will last and what won’t.”

Sebald’s awareness of how easy it was to distort reality through doctored photography (long before digital manipulation became commonplace) manifests in his repeated interpolation of Nazi propaganda: clearly manipulated photographs and video stills appear throughout his books. “How could he both want to shock us with the reality of his photos and at the same time remind us that they could be fakes?” Angier asks about these images. “It’s an insoluble question.” Rather than using images to backstop the reality of the prose, however, Sebald instead plays the two media off of each other in a deliberate attempt to invoke precisely the contradiction that Angier identifies. Sebald’s solution is not to abandon documentation, but rather to repeatedly demonstrate its insufficiency; what seems initially to be a surplus of documentation, with images that superficially verify their accompanying text, is instead a project collage meant to highlight disjunctions, contradictions, and ambiguities.

Sebald does not abdicate the role of confronting the past: By pushing a surface agreement between writing and image to the point where the fractures become evident, his goal instead suggests that the work of recuperating the past must be one of constant activity, of constantly cobbling together sources — each of which, on its own, is unreliable. The goal is never to reconstruct the past, but to gesture towards its historical ruptures that can never be fully sutured closed.

The Rings of Saturn opens with a discussion of Sir Thomas Browne, the 17th-century writer who lived in East Anglia. Sebald muses on whether or not Browne, then a medical student in Amsterdam, was present at the 1632 dissection of Aris Kindt, who had been executed for armed robbery. Kindt’s dissection was the basis for Rembrandt’s famous painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, which shows a gaggle of doctors inspecting Kindt’s corpse. As Sebald notes, the assembled doctors’ gazes are not on his corpse, but on the anatomical textbook at its feet. The text supplants the reality of the body in front of them.

Sebald notes that “the much-admired verisimilitude of Rembrandt’s picture proves on closer examination to be more apparent than real.” The dissection is being carried out in the wrong order, with the arm dissected before the abdomen (as would have been standard), and, what’s more, the dissected hand is anatomically incorrect. In other words, “what we are faced with is a transposition taken from the anatomical atlas, evidently without further reflection.” He argues that this mistake was intentional: “That unshapely hand signifies the violence that has been done to Aris Kindt. It is with him, the victim, and not the Guild that gave Rembrandt his commission, that the painter identifies.”

This reveals a broader pattern in Sebald’s work — if straight documentation is itself liable to misremembering, perhaps the way forward is through deliberate distortion. Perhaps the work of the artist is not merely to record the violence of the past, since too often the official means of preserving the past are themselves invested in that violence. Artistic distortion, he implies, can be a deliberate, creative means of undoing state violence.

Sebald’s answer may be unsatisfying in an age of fake news and deliberate misinformation, where it seems like the only resort is to cling steadfast to some notion of truth and objectivity. But there’s been a longstanding, naïve belief (particularly among liberals) that the way to combat disinformation is by stubbornly asserting the “truth” and the “facts.” We’ve seen acutely in the last few years how easily conspiracists and bad actors simply disregard empirical documentation altogether. From Holocaust denial to Trumpist election truthers, we’ve seen how firmly rooted an ideologically based rejection of reality can be, and how heaping fact upon fact and photograph upon photograph is only ever sucker’s progress. There are definite exceptions to this, of course (most notably, the number of white centrists and liberals who’ve been made aware of police brutality through cellphone videos), but the echo chambers of social media and the ever-increasing ideological polarization of culture has made it increasingly impossible for factual documentation to meaningfully persuade, even when used as a bludgeon.

For a writer obsessed with the question of recovering the past, Sebald takes pains to remind his reader that not only is memory unreliable, but so are the technologies that aid it

Sebald’s work anticipates our current morass by moving in a different direction altogether. His books model a much more active process, one that involves the collection of history and memory through imperfect sources, rather than the passive reception of immutable facts and documents.

Perhaps this explains the image in Sebald’s work that haunts me most. Sebald’s final novel, Austerlitz, tells the story of its Jewish protagonist, who as a young child was sent out of Prague on the kindertransport to be raised by foster parents in Wales, never discovering his early origins until he is a young man. As an adult, he begins an attempt to track down evidence of his parents, both of whom died in the Camps. Eventually, he learns that his mother Agáta was deported to Theresienstadt, which the Nazis maintained as a sort of theatrical façade of humane living conditions. Jacques Austerlitz finally tracks down a propaganda film made for the Red Cross, in which he glimpses a woman he believes to be his mother. Watching the seconds-long snippet of the film again and again, Austerlitz fixates on the woman who looks “just as I imagined the actress Agáta from my faint memories and the few other clues to her appearance that I now have.”

But the image itself is tricky: the film is, after all, a work of propaganda. Noam M. Elcott, in his study of the layout of Sebald’s texts, quotes Erwin Panofsky’s discussion of the propaganda films of the Third Reich: “I believe — and please do not repeat this — that there is no such thing as an authentic ‘documentary film’ and that our so-called documentaries are also propaganda films except, thank goodness, usually for a better cause and, alas, rarely as well made.” Panofsky’s remark here is doubly important: at times the only documentary source available is propaganda, or other modes of state repression, which makes the archived material both precious and thoroughly suspect.

And so, rather than simply represent the state propaganda as a some form of “true” documentation of the past, Sebald alters the image. “I run the tape back and forth,” Austerlitz says, “looking at the time indicator in the top left-hand corner of the screen, where the figures covering part of her forehead show the minutes and seconds, from 10:53 to 10:57, while the hundredths of a second flash by so fast that you cannot read and capture them.” In the image reproduced in the book, the woman’s face, already distorted from the poor VHS tape quality, is further obscured by the tape’s time code itself, the numbers blotting out much of her face. It is not Agáta who is the focus here, but the time indicator. There is no real moment of recognition, no epiphany or sudden flood of memories for Austerlitz — she is not Agáta so much as the person he imagines Agáta to be, based on unreliable clues. No amount of documentation could ever truly overcome this gap.

Which is to say, sometimes when we go seeking the past, the best we can hope for is not some kind of reconnection, so much as a reminder of the stubborn passage of time that severs us from the past. The mistake is responding to this impossibility with a feeling of resignation and futility, when instead it is our task and privilege to respond to it with urgency.

A few months before his death, Sebald delivered a lecture at the Literaturhaus in Stuttgart titled, “An Attempt at Restitution,” where he suggested that literature exists “only to help us to remember, and teach us to understand that some strange connections cannot be explained by causal logic…” At the end of the talk, he adds this final elaboration: “There are many forms of writing; only in literature, however, can there be an attempt at restitution over and above the mere recital of facts, and over and above scholarship.”

Taken together, these two lines indicate the heart of Sebald’s project: an attempt to move beyond the mere recital of facts — the mere presentation of documents, the mere evidence of photography and archival material — and attempt, through a kind of associative process that relies on metonymy, coincidence, the uncanny, and chance, to attempt to restore some measure of justice to the past. Sebald’s literary project was at once to spur the reader’s investigation into the past while refusing to sum up or neatly tie it off: to push back against a passive and complacent reception of history and the archive by simultaneously insisting on and undermining their veracity. Photography, as with other means of documentation, remains necessary but not sufficient — it contains vital traces of the past even as it obscures our relationship to it. Any attempt at restitution is inherently collaborative, and forever ongoing — the work we are obliged to re-commit ourselves to daily.