Well Played is a monthly column about video games and how they both reflect and shape capitalism’s development. What role do they play in reproducing society, transforming ideology, and sustaining capital’s pool of labor? The answers suggested here are meant as openings for debate rather than comprehensive, conclusive statements; exceptions to some claims may be obvious, but these don’t nullify the general trends, which must be met with social resistance. This series is offered as a contribution to a map of the territory for those who would join that conflict.

Over time, the phrase video games has become only more accurate and appropriate: Twitch streaming, YouTube, and e-sports have bifurcated the video-game experience into two increasingly separated modes: playing and watching. For early theorists, the medium-defining feature of video games was interaction — haptic feedback, touch and play. Now video games are increasingly experienced as video, as entertainment that does not depend on directly playing the games oneself. As sociologist T.L. Taylor demonstrates in her recent and crucial book Watch Me Play, watching games has become central to gaming culture, the games industry, and popular culture more generally. Her insights inform much of what follows.

The televisual market for video games is split into two modes. The first is prerecorded content, accessed mostly through YouTube. This tends to be a mix of recordings of live streams, edited let’s plays, memes, video-game highlights, instructional videos, advertisements, games journalism, and industry events. Such material makes up a tremendous amount of the video-game content consumed on the internet, and it has a huge audience — Markpillier, PewDiePie, and relative newcomer Vanoss Gaming consistently top lists in YouTube revenue and subscriber count. It also has more in common with other forms of social media, online fandom, and YouTube culture generally: communities of fans form around content that is a mix of traditional cultural production and “personal” vlogging, usually driven by a core personality or concept, ending up halfway between a TV show and a personal lifestyle magazine, but more amateurish, “authentic” and “unfiltered.”

Live streaming ends up being a constant performance of crowdfunding as entertainment, like a low-rent telethon

Games particularly lend themselves to this kind of treatment, but it’s pleasurable to watch any hobby you enjoy become a performance. Thanks to a profusion of broadcast platforms, media-making capabilities, and institutionalized surveillance, almost anything imaginable can make it to the screen, whether in YouTube clips, live streams, or workplace TikTok videos. This profusion of content can be a tremendous source of learning: For example, queers can learn to dress, speak, or do makeup how they want in situations where they may not be able to be out safely. DIY skills can be picked up on the fly. Lectures and documentaries have become far more accessible. But accessibility to video content beyond the conventional channels has also sent people down rabbit holes of hatred, stupidity, and paranoia.

The other video-game-viewing mode is the live stream, in which streamers play games for live audiences. The capability for individual producers to live stream has existed almost as long as technology and internet speeds would allow it, but with video-game streamers, it has become much more of a mainstream trend. Why video games? In some respects it is like watching conventional sports or live theater: There is the simple pleasure of watching someone perform a highly skilled task without do-overs. This aspect of video-game watching is fairly banal and typical. With their built-in stakes, games are sufficiently compelling when presented without a lot of pre-production, unlike other popular internet-video topics like cooking, DIY, makeup tutorials, or even personal diary-style vlogging. And games are easy to follow without paying full attention, which accommodates viewers who are multitasking. Unlike conventional TV programming, games don’t have to build stories or arguments, which require sustained focus on the viewers’ part. While some games are full of story, the most popular games for live streaming are multiplayer competitive games like Fortnite, which have easily gauged metrics, stakes, and conditions. They make no demand for continuous attention, though they are action-packed enough to reward it.

In general, the temporality of gameplay — both fast and slow, full of constant new action and reliable structured repetition — lends itself well to ambient live consumption in a way that little other watched amateur content does. There is both very little downtime in such games and, in another sense, nothing but downtime. They can be simultaneously fully engaging and easily ignored. They constantly give audiovisual stimulus pitched to capture viewers’ attention, but live streams are just as easily talked over, ignored, left on in the background, walked away from, and returned to depending on how viewers choose calibrate their attention.

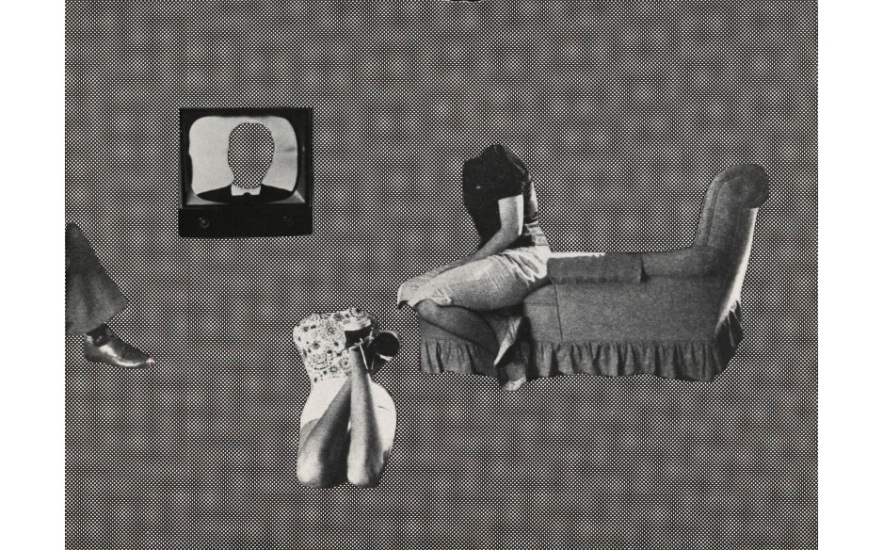

These aspects of gameplay temporality point to the specific pleasures of watching video-game live streams. Unlike scripted entertainment, which invites viewers to be swept up into a story, escape from mundane reality, and possibly vicariously identify with lives not one’s own, watching someone else play video games addresses a broader set of responses to a screen, derived specifically from the affective space viewers inhabit while watching. This space is both intimate and alienating, lonely and social — that is to say, it is characterized by some of the same contradictions of life lived with and through screens. This homology is part of what makes game watching a defining aspect of daily life for millions of people.

The aesthetics of a live stream are incredibly visually noisy and, at first, almost overwhelming. Usually gameplay takes up most of the app or browser window, while a web camera pointed at the streamer displays them looking at their screen on a picture-in-picture in one corner. There are lists of donators, comments, info about the music playing, and there is a fast-moving chat window, powered by the special blend of emote meming and copy-pasta enabled on streaming services like Twitch and Discord. This chat often includes people who know each other, either from offline or through the streamer’s channel and servers; they may be catching up and hanging out as the streamer plays, with the game serving less as a focus than a pretense for general socializing.

As the game is played, various animations and memes, special to each stream and streamer, will randomly pop up on the screen, often linked to donations or subscriptions and usually accompanied by a few-second-long sound sample that repeats loudly. These repeated, often humorous disruptions become hypnotic and rhythmic — like the noises of a casino — encouraging further participation by new viewers: Subscriptions and donations will often snowball. The streamer will also usually thank subscribers, read out their messages and shout out their screen names. Hence, streamer success is marked by constant interruption, eruption, chaos, and noise as the streamer’s impetus to professionalize and monetize their practice takes on specific aesthetic consequences. The more popular a stream is, the more consistently it will be interrupted. A streamer who is just quietly playing a game for your entertainment is probably not making any money.

This combination of buzzing sociality in the chat with the chaotic bell-ringing of the streamer’s commercial celebrations turns a “successful” stream into a kind of riotous digital party. Participation in the stream is not merely a question of passive watching or even chatting but also making micropayments to maintain the stream as both a means of subsistence for the streamer and as a lively, interactive place for other viewers.

Many viewers wish they could “just play video games” for their living. Consuming that fantasy is part of why they watch

Live streaming thus ends up being a constant performance of crowdfunding as entertainment, like a low-rent telethon — and even successful streamers are pressured by economic necessity to stream very long days, seven days a week: Every day off represents a loss in revenue, as audiences drift away or spend their subscription and attention dollars elsewhere. A few super-successful streamers will get rich, a handful more will live middle-class existences off their programming, but most will make nothing or next to nothing, all while working crazy hours staring into a digital mirror.

The live stream thereby epitomizes and romanticizes a number of trends in capitalist labor: It stages the precarity of wages as a kind of celebration while granting consumers symbolic sovereignty over streamer-workers. The joy of the viewing crowd is prioritized over the well-being and needs of individual streamers — here a metonym for workers in general — as they become not just entrepreneurs but microcelebrities, vulnerable to all the violence, instability, and disorientation a celebrity economy entails, only to much smaller reward. Work is posited as an endless, always-on component of life, rationalized as a mutual form of entertainment, a kind of doing and sharing what you love — if only you’re able to work hard enough and be good enough. Meanwhile, though more and more people are drawn into these forms of affective labor and performance — you can play video games for a living! — money and attention concentrates in fewer places and people.

To their credit, many streamers have spoken out about this situation, and no doubt a lot of conversations about working conditions go on in the DMs. But thus far, little has happened publicly beyond occasional on-stream complaints and some streamers forming basic, nonpolitical cooperatives. It’s difficult for streamers to organize as workers, as the nature of their work typically places them alone in their bedrooms in competition with one other for viewers. In this alienation they are like most workers in the gig economy. Streamers usually come together only in one another’s streams or chat spaces — in their hyper-public workplace — or at industry events, like Twitchcon, where they are less likely to organize and more likely to be coerced by the platforms (i.e. their bosses, who make the real money) into expressions of gratitude, celebration, and brand identity.

Viewers may have little sympathy for streamers’ public complaints, not only because of the generally reactionary organization of video game fans (as detailed previously in this column) but because their envy is part of how streaming is structured affectively. Many of them wish they could “just play video games” for their living. Consuming that fantasy is part of why they watch.

All the violence, consumption, and capitalist reproduction that occurs within streaming “works” as entertainment and pleasure only because the affective dimensions of streaming are also intimate, personal — even romantic. Streaming platforms are able to exploit viewers and streamers alike because people love games and love to play, invent, and create community. Games connect so many of us to our childhoods, to our most cherished spaces of imagination, wonder and joy: watching others play gives us direct access to these experiences of nostalgia. Streamers succeed because we get to know them, to love them, and because we can build a fan community with and around them. They produce a sense of belonging within the often atomizing context of a life organized by screens.

While these trends make room for micro-cults of celebrity and sometimes near demagogic power among YouTube personalities, they also provide space for connection, friendship, and organization. The fact that fascists have thus far made the most of these spaces — seizing upon them to organize and indoctrinate (even as they get repeatedly doxxed by anti-fascists) — reflects the current social base of organized gamers and not something intrinsically terrible about games or the idea of online community itself.

As community and culture increasingly fracture, as long tails of culture proliferate and mass culture recedes further into the past, as algorithmic sorting turns marketing into a game of hyper-specification and individuation, the experience of play — even when taken through heavy layers of alienation and mediation —becomes a core communal salve, a means of participating in togetherness and relaxation. These sites can be places of sharing resistant cultures, affects, and games. They can foster independent creativity and the creation of independent communities, and rebellion can proliferate in even the most seemingly structured and controlled spaces.

Capitalism is always making and remaking its own gravediggers: Whenever we finally start playing the great joyful game of revolution, maybe we’ll have been given some ideas about how to include all our friends.