It has often been said that certain of us are living through a long crisis of futurity. Communist theorists and tech self-help gurus alike have been declaring for years that the future has been “cancelled”: foreclosed, rendered all but impossible to imagine, or at least not in ways that can help us create a better world in the present. One hope some commentators had in the spring of 2020, as epidemic turned to pandemic, was that global disaster would have the salutary effect of dislodging this collective future block. In an essay published in April 2020, Arundhati Roy likened the pandemic to “a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.” This line, with its metaphysical optimism and its evocation of other such epochal pronouncements — Antonio Gramsci’s “the old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born”; Roy’s own “another world is not only possible, she is on her way” — became a sort of unofficial slogan for a reinvigorated futurism in the early months of the pandemic. Experts clamored to weigh in on what, exactly, this “next” world would look like. An endless series of think pieces and white papers speculated on “the future of x after Covid”: of restaurants, of travel, of live music, of work itself. Suddenly the future, like so many products of culture, was rebooted. If on the other side of the portal, nothing would remain untransformed, on this side nothing would remain unspeculated-on.

These sweeping predictions formed something like a dialectical counterpoint to that other early pandemic trope of the future: the return to normalcy. And yet here too was an opportunity for limitless speculation. What better object of predictive gamesmanship could there be than the virus itself — when it would surge, and when, like a patch of bad weather, it would recede and allow life to continue on as before? In the anglophone world, David Leonhardt’s New York Times newsletter has been the most prominent organ of this mode of speculation. Armed with an inexhaustible supply of infographics and statistical analogies, Leonhardt has repeatedly speculated that the time is ripe to return to normal. On this score his record has been legendarily bad: “Good morning. Is it time to start moving back to normalcy?,” read a headline for a newsletter published just two weeks before the arrival of the omicron variant in the U.S.

There is a secret sympathy between “This Changes Everything” and “Return to Normalcy”

Despite appearances, there is a secret sympathy between the This-Changes-Everything columns and the Return-to-Normalcy screeds. Both forms of speculation proceed from a common dream of a unitary Next Thing: a totally new “world” where everything is either transfigured, or restored to how it used to be. In the World Economic Forum’s ominous declaration that the pandemic presented a “rare but narrow window of opportunity” for a global “Great Reset” — an initiative the organization had been trying to push for some time before the pandemic — both visions collapsed into one.

In 1970, futurists Alvin and Heidi Toffler coined the term “future shock” to explain the experience of “too much change in too short a period of time.” As the breakdown of the Fordist industrial order and the attendant sweeping technological advancements radically reconfigured social life in the affluent societies of the global north, people’s senses were apparently overwhelmed. Future shock was a restless yet paralyzed “response to overstimulation.” (Gilded-Age patent medicine salesmen had a pithier name for such a condition: “Americanitis.”)

The premise of future shock, though, was that the future had already arrived. The speculations of the past two years, on the other hand, have been directed at a properly futural future; one that has not yet come, one characterized by a dizzying sense of infinite possibility, for better or for (much) worse. Call it future vertigo: A sense of teetering on the edge of something radically new, casting down pebbles in a futile attempt to sound its depths.

The plunge, of course, never happened. No body of experts, no government, no corporation has been able to deliver a Next Thing. The now clichéd chronotopes of the pandemic testify to this non-arrival: the heightened sense of time as spatial, with every country, state, city inhabiting a different “era” in pandemic time — each on a different “wave” — and the general philosophical lament what even is time anymore. It turns out that there is no one future so much as there is a series of ongoing crises smoldering in the background, distributed unevenly at every level. Amid this atmosphere of what Alexandra Molotkow has called “reality disappointment,” as the much-hyped “after” arrives without the transformation or reconciliation it once promised, speculation on the Next Thing has become an increasingly tough sell.

One of our technologies of speculation has recently started to register this futility with a special sensitivity: not the TED talk, the white paper, or the infographic, but the homelier and more immediate trend piece. Surely if grand speculation about the “next world” has proven unviable — though undeniably lucrative for some practitioners, to the point that futurists have offered online courses on post-Covid prophesying — at least we can try to catch the next style or subculture in its process of coalescing.

The goblincore devotee imbues everyday messiness with the lite gravitas of lifestyle

And yet a scan of the most-speculated-on recent trends yields something curious. If the 2010s introduced -cores and –waves to popular culture, with slightly facetious tags like normcore and vaporwave laying claim to free-floating elements of the zeitgeist, the pandemic years have seen an exponential multiplication of these suffixed “aesthetics,” beyond what any one person could hope to keep up with. The crowdsourced “Aesthetics Wiki” was created in 2020 to index these proliferating categories — and, as Dylan Davidson has noted, to present them to the reader hunting for a sense of belonging as so many “identificatory menu item[s].” These are not expressions of a unitary Next Thing, but discrete subcultural elements, soon to be superseded by another or others.

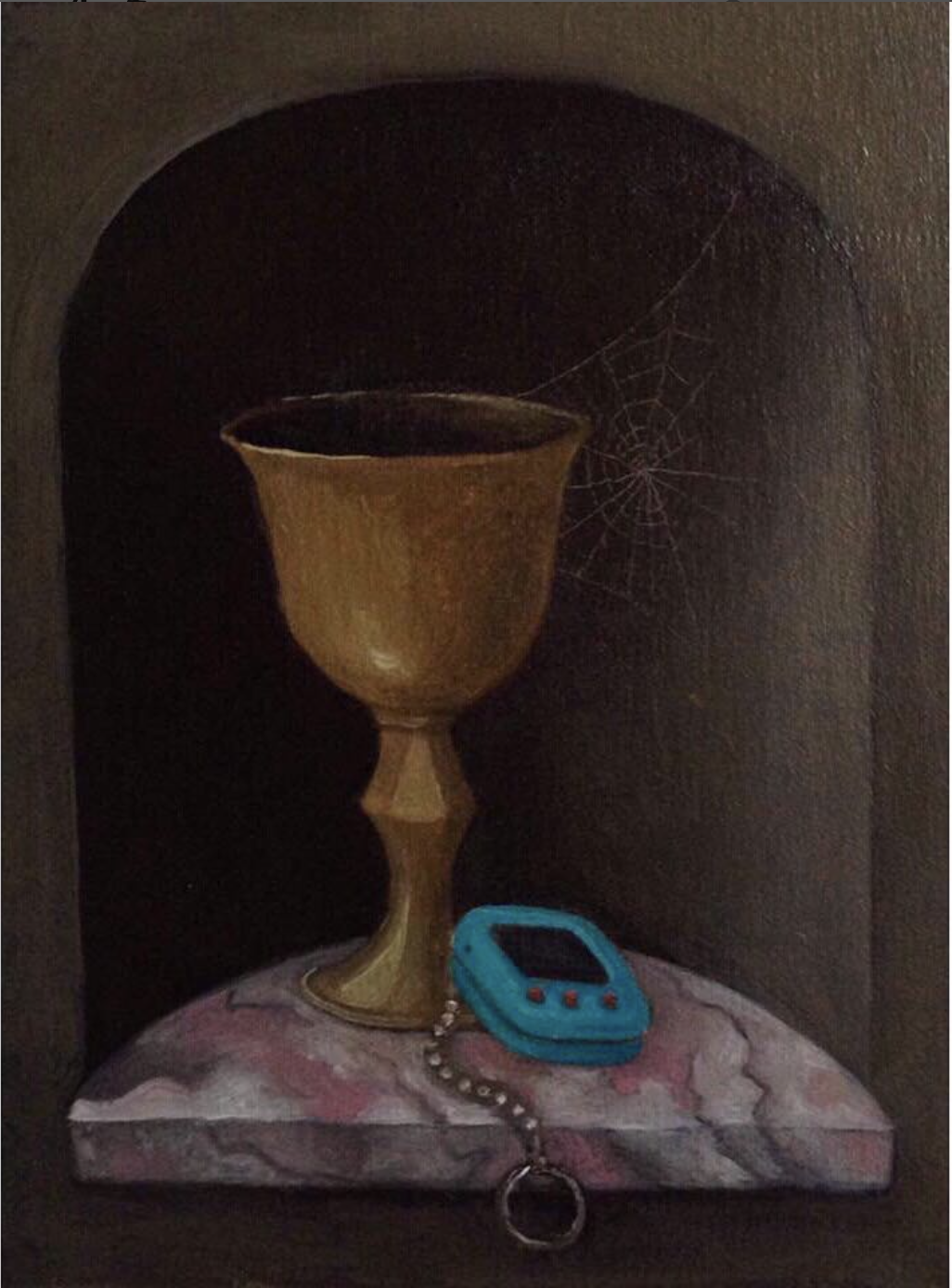

The styles that have recently risen out of this internet soup and into the sphere of trend pieces have reflected a certain fatigue with the churn of trend itself. “Goblincore,” the aesthetic that recently launched a spate of trend pieces and even a self-help book, is perhaps the most paradigmatic anti-Next-Thing. Its adherents hardly have avant-garde aspirations. For the goblincore devotee, the goal is to elevate everyday messiness to a sacred principle — to build a private fort of garbage in which to binge Netflix, or else to roll around in the dirt in order to feel some measure of unity with nature, and to imbue it all with the lite gravitas of lifestyle. With its professed allegiance to all things “feral,” which is to say uncurated, and its preference for “vibing and existing, not fitting into a mold,” goblincore is in a real sense an aesthetic about giving up on the cycles of trend, about turning one’s back on the zeitgeist and going off to hoard shiny objects in a junk-strewn hovel.

It is an especially potent strain of the anti-futural orientation Olivia Stowell identifies in the “dark academia” aesthetic, which has readapted the tweed style of midcentury Ivy-League distinction for the age of future-obliterating student debt. This orientation has reached a hyperbolic extreme in “cluttercore,” an apparently sincere attempt at a messily maximalist alternative to Kondo-style minimalism, as well as B.D. McClay’s tongue-in-cheek manifesto for “gnomecore,” a synthesis of goblincore’s slovenliness with a minimal dose of Bauhaus practicality that will apparently yield the “last [trend] we will ever need.” Across all these -cores and -waves that have spread like the mushrooms goblincore adherents admire so much, a quiet consensus emerges: there will be no Next Thing. Only detritus — old books, pressed flowers, dirty clothes — piling up in the here and now. Where futurists in all sectors recently saw a yawning future that would either be radically different from, or exactly identical to the immediate past, adherents to the latest -cores and -waves now simply see a scattering of individuals vibing, vegetating. For them, perhaps, speculation’s spell is losing its power. Future vertigo gives way to future fatigue.

By far the most notorious recent trend piece on the Next Thing is Allison P. Davis’s essay on the supposed coming “vibe shift.” In that essay, which as McClay points out is “a piece not so much about a trend as the idea of trends,” Davis follows the recent efforts of futurist-consultant Sean Monahan, coiner of “normcore” in the early 2010s, to figure out what is Next. Is it “opulence”? A return to “early-aughts indie sleaze”? A retreat from “political considerations” and an embrace of some kind of general and targetless “irony”? Monahan, like so many futurists, is flailing. He is “theorizing on the fly,” as Davis puts it, seeing if anything will stick.

It is a fascinating glimpse into futurism in process, as it tries to grind its way out of an impasse. On the one hand, Monahan is clearly attuned to the zeitgeisty sense of zeitgeistlessness. He picks up on a creeping social media fatigue, and the attendant wish to return to an earlier era of the internet where social life wasn’t concentrated on what he calls a few “Sauron-esque” platforms, but dispersed across thousands on thousands of micro-niches. Not social networks, but blogs, newsletters, apparent refuges for the “personal” amid an impersonal crush of hypermonetized content. On the other hand, he can only think of this supposed will to cultural diffusion as itself an incipient and unifying cultural mood — a total vibe shift coming for us all. The Next Thing, Monahan seems to be struggling to articulate for the subscribers to his paid newsletter, may be No Next Thing. Declaring No Next Thing outright as the Next Thing would be the ultimate admission of defeat for the professional speculator. More than two years into the pandemic, to make such an admission would be to close Roy’s portal once and for all.

Was it Walter Benjamin or Meat Loaf who said that the future ain’t what it used to be? Untold millions of former Next Things languish in dusty magazine archives, cached away on orphaned webpages, buried in a drift of ahistorically sorted content. There is no kitsch quite like the artifacts of a promised future that didn’t pan out: hovering vacuum cleaners, 3D glasses, the DeLorean. Even the speculations of the recent past feel impossibly naïve. Who couldn’t have foreseen the collapse of the dot-com bubble or felt the yawning nullity at the heart of the NFT craze? To ask this question is to grasp the Yogi Berra-ism at the heart of that elusive thing we somewhat sententiously call historical consciousness.

Future vertigo gives way to future fatigue

As the junked Next Things continue to pile up around us (Davis memorably starts her essay with an invocation of the “‘hot vaxx summer’ that never really was”), it may be that the realm of online trend is the place where an ambient loss of faith in speculation’s power has found its first vernacular expression. The experts have failed to deliver our shiny future: no global reset, no return to normalcy. Forms of hyperbolic speculation like last year’s kidding-but-not-kidding run on Gamestop stock, or even the bargain-basement-Nick-Land visioneering of reactionary Substacker “Angelicism01” — who, as Will Harrison points out, proclaimed the coming of a “vibe shift” before Monahan — are only the dialectical flipside of this loss of faith.

Of course the pandemic hardly created the fantasy of a universal future; it only intensified it, invested it with a particularly urgent charge of desperation. If the past two years have produced any genuinely new development in the history of the future, it is perhaps a widespread, if faintly felt, consciousness of stagnation; a growing conviction that a sweeping Next Thing is not forthcoming.

This is what the aspiring goblins and cluttermongers have grasped, however inchoately. They have given a concrete, if degraded, form to a general exhaustion with the theological conception of the Next Thing: the future as a divine dispensation handed down to us from above. Maybe, then, if we squint hard enough at the glittering dump of post-trend, we can make out the faint outline of a more useful way of thinking about the Next Thing: not as a program delivered to us by tech overlords, but as a result of practical human activity, as a series of projects that may or may not converge — that is, as a matter of DIY.